Neo Eocene (project)

(For a nice review of the project see Daniel Pierce's article in Vice Magazine 24 October 2016)

There is broad scientific consensus that we are well into a period of rapidly escalating, human-induced climate change. But how high will temperatures go? Some models predict that global temperatures could increase by as much as 5 degrees C. The last time this happened was during the Eocene Thermal Maximum, some 55 million years ago. This was long before our own species came along, so it is unclear how we will be able to adapt to the coming extremes. Back in those days, palms and alligators flourished as far north as what is now Alaska and the Canadian Arctic. Much of British Columbia was covered in a warm temperate forest, far more biologically diverse than what exists here today.

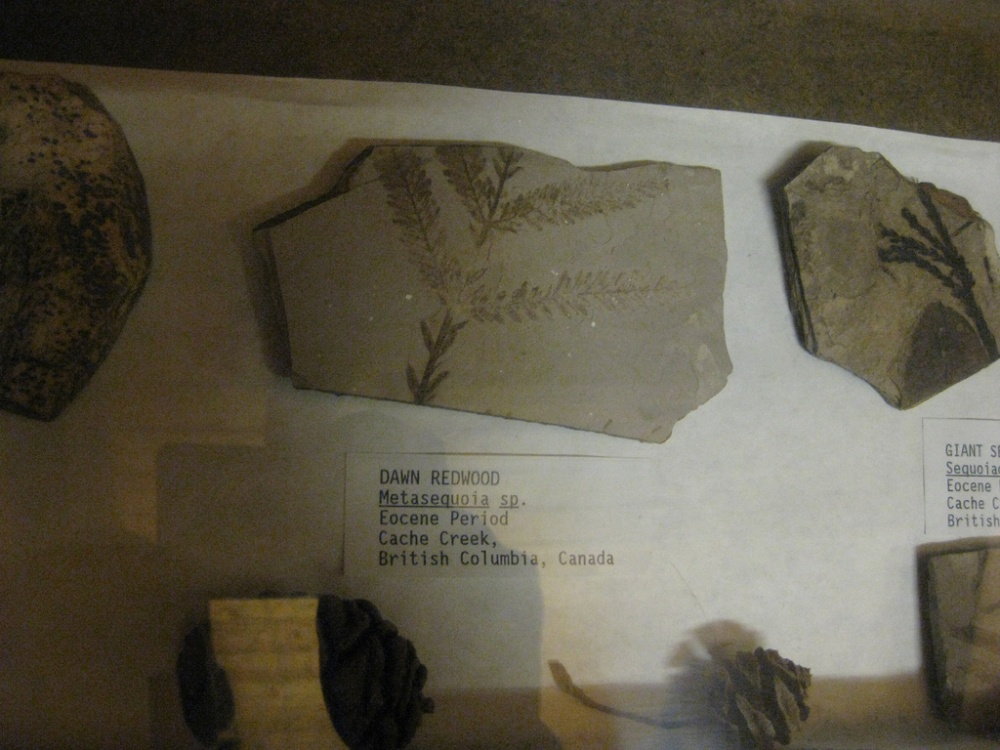

Imagine groves of such now exotic trees as Dawn redwood, Gingko and Cunninghamia growing natively over a vast swathe of Western Canada and down into Washington and Oregon. Their leaves, seeds and flowers are still preserved in exquisite detail in the fossil deposits of various localities from Cache Creek to Kitsilano. Their close relatives still exist, albeit in much diminished ranges, in parts of China and the southeastern United States but a long-term cooling trend extirpated them from our area ages ago.

But if global warming threatens to bring back the Eocene's temperatures, why not reintroduce the Eocene's trees? Many of our existing forests have already suffered substantially under the newer, hotter conditions - most of all the Interior pine forests, ravaged by beetles that are no longer being killed by cold winters. We can hope the forests might survive by retreating northward, but the indications are that the rapidity of the warming could easily outstrip the natural processes of plant migration.

That's where we come in. Over the past dozen or so years, I have been introducing into my yard some of the tree species that once made up the Eocene forests of British Columbia and have been tracking their progress. Metasequoias in particular have done spectacularly well and a couple of my ten year-old specimens have reached over 8 metres in height. These are amazing trees - deciduous conifers long though to have been extinct and causing a sensation when they were found surviving in a remote part of China back in 1944. Yet their fossil remains are distributed throughout the Northern hemisphere, from mid latitudes right up to the high Arctic where their deciduous needles might have conferred them an advantage during the darkness of the polar winter.

More of my successful reintroductions include Tetracentron, Scadiopitys, Cunninghamia, Podocarpus, Sequoia and Trachycarpus palms-all of which flourish without winter protection, despite frosts as low as minus 15C and frequent deep snow.

Members of the Juglans family (hickory and walnut) have also adapted well to my Cortes Island locality and I am steadily introducing other broad-leafed species to see how they do.

In 2008, I embarked on a collaboration with the British botanist Rupert Sheldrake to scale up my initial trials to a landscape level. This project involved planting entire groves of Metasequoia, Juglans, Gingko and Coast Redwood and arranging them in clines, or habitat gradients on Sheldrake's property - a 60 acre clear cut on the east side of Cortes Island. The winter and spring after planting (2008-2009) have been exceptionally dry but a good portion of the plantings have survived thus far without any supplemental watering. The Juglans and Sequoia in particular have taken well, on what is for the most part a very exposed site, heavily disturbed by industrial logging. Work on this "Climate Change Forest” is ongoing and our hope is that the successes and failures in establishing the various tree species will yield some useful information on the future of forests under conditions of rapid global warming. Perhaps some of the trees might possess a kind of genetic memory and will once again flourish in BC's forests as they did so many aeons ago. If that is the case, the reintroduction of these Eocene survivors might prove part of a larger strategy to manage the climate cataclysm that has only just begun.

Slide Show:

projects:

events:

-

Thursday, March 20, 2025 - 12:00 - 13:00

-

Tuesday, April 26, 2022 - 03:30 - 16:30

-

Friday, April 1, 2022 - 18:00 - Monday, April 4, 2022 - 12:00

-

Friday, April 1, 2022 - 09:00 - Sunday, July 31, 2022 - 17:00

-

Wednesday, December 8, 2021 - 21:45 - 22:45

-

Friday, November 5, 2021 - 13:45 - 16:00

-

Tuesday, October 12, 2021 - 13:30 - 14:15

-

Monday, June 28, 2021 - 10:00 - 11:00

-

Thursday, March 19, 2020 - 12:00 - Sunday, March 22, 2020 - 00:00

-

Friday, October 25, 2019 - 21:00 - Sunday, October 27, 2019 - 23:00

-

Thursday, August 1, 2019 - 12:00 - Wednesday, October 2, 2019 - 00:00

-

Friday, April 26, 2019 - 21:30 - Saturday, April 27, 2019 - 00:30

-

Friday, March 29, 2019 - 23:00 - Sunday, March 31, 2019 - 21:00

-

Sunday, June 24, 2018 - 12:00 - Saturday, July 7, 2018 - 22:00

-

Friday, June 22, 2018 - 12:00 - Sunday, September 30, 2018 - 20:00

-

Saturday, June 9, 2018 - 12:00 - 19:00

-

Saturday, May 19, 2018 - 15:00 - Sunday, November 11, 2018 - 22:00

-

Sunday, April 22, 2018 - 13:00 - 23:00

-

Friday, April 13, 2018 - 22:00 - Sunday, April 15, 2018 - 17:00

-

Friday, January 26, 2018 - 09:30 - 11:00

-

Saturday, July 1, 2017 - 03:00 - Sunday, August 27, 2017 - 03:00

-

Friday, May 26, 2017 - 12:00 - Saturday, May 27, 2017 - 15:00

-

Sunday, May 14, 2017 - 13:00 - 17:00

-

Sunday, April 30, 2017 - 20:00 - 22:30

-

Sunday, April 9, 2017 - 18:00 - 20:00

-

Tuesday, November 15, 2016 - 14:00 - 16:00

-

Tuesday, April 12, 2016 - 17:00 - 18:30

-

Tuesday, March 1, 2016 - 12:00 - Monday, June 6, 2016 - 21:00

-

Thursday, February 25, 2016 - 14:15 - 14:30

-

Tuesday, February 16, 2016 - 14:15 - Wednesday, February 17, 2016 - 00:45

-

Wednesday, December 2, 2015 - 22:00 - Sunday, December 6, 2015 - 22:00

-

Saturday, November 21, 2015 - 19:00 - 21:00

-

Friday, September 18, 2015 - 03:00 - Monday, December 7, 2015 - 02:59

-

Saturday, May 16, 2015 - 16:00 - 19:00

-

Friday, April 17, 2015 - 19:00 - Saturday, April 18, 2015 - 22:00

-

Wednesday, February 25, 2015 - 03:00 - Wednesday, March 25, 2015 - 03:00

-

Tuesday, November 11, 2014 - 20:00 - Wednesday, November 12, 2014 - 00:00

-

Monday, September 22, 2014 - 12:00 - Sunday, September 28, 2014 - 02:00

-

Wednesday, July 30, 2014 - 12:00 - Monday, August 4, 2014 - 01:00

-

Tuesday, July 22, 2014 - 13:00 - Friday, July 25, 2014 - 19:00

-

Wednesday, March 19, 2014 - 21:00 - 22:00

-

Saturday, March 15, 2014 - 12:00 - Friday, March 28, 2014 - 12:00

-

Thursday, March 6, 2014 - 19:00 - 21:00

-

Tuesday, February 25, 2014 - 14:00 - 15:15

-

Friday, October 25, 2013 - 11:30 - Saturday, October 26, 2013 - 19:00

-

Saturday, September 28, 2013 - 20:30 - 23:30

-

Monday, September 16, 2013 - 03:00 - Wednesday, September 25, 2013 - 02:59

-

Sunday, May 26, 2013 - 18:00 - 21:00

-

Saturday, May 25, 2013 - 14:00

-

Thursday, May 9, 2013 - 18:00

-

Thursday, February 21, 2013 - 22:00 - Friday, February 22, 2013 - 00:00

-

Thursday, February 7, 2013 - 17:00 - 19:00

-

Tuesday, December 4, 2012 - 22:30

-

Sunday, September 30, 2012 - 21:30 - Monday, October 1, 2012 - 00:00

-

Wednesday, September 26, 2012 - 20:00 - Thursday, September 27, 2012 - 00:00

-

Saturday, August 25, 2012 - 16:00 - 19:00

-

Friday, June 1, 2012 - 14:00 - 16:00

-

Friday, February 17, 2012 - 21:00

-

Thursday, January 26, 2012 - 15:00 - 17:00

-

Friday, November 18, 2011 - 21:30 - Monday, November 21, 2011 - 00:00

-

Sunday, September 18, 2011 - 13:00

-

Saturday, September 17, 2011 - 13:00 - 17:00

-

Saturday, June 25, 2011 - 13:00

-

Thursday, June 23, 2011 - 22:00

-

Wednesday, June 22, 2011 - 22:00

-

Thursday, May 5, 2011 - 22:00

-

Thursday, October 28, 2010 - 22:00 - Friday, October 29, 2010 - 01:00

-

Tuesday, June 1, 2010 - 21:00 - Wednesday, June 2, 2010 - 00:00

-

Friday, April 16, 2010 - 23:00

-

Wednesday, March 31, 2010 - 22:00 - Thursday, April 1, 2010 - 00:00