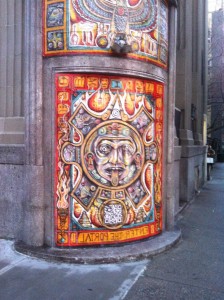

It’s the last day before the NYU students’ Christmas break and the streets of the East Village are full of drunken Santas and inebriated elves vomiting, fighting and staggering into traffic. For some reason this makes me very happy – a debauched anti-Christmas that serves to de-alienate me from the saccharine strains of seasonal Muzak and ersatz bonhomie that are so hard to get away from at this time of year. In keeping with the looming end of the Mayan calendar, a young hipster is getting his picture taken next to the Meso-American themed ‘portal’ he has pasted onto the old bank building on the corner, complete with the now obligatory QR code to link our smartphones to his on-line brand. And he is looking mighty pleased with himself. Sadly, the real Armageddon turns out to be a much slower, more painful, affair, which we’ll have to spend many more years enduring, despite all the prophesying and anticipatory hippie dancing down there in the Yucatan. A day after the anticipated end of the world, the ‘portal’ is already peeling- its wheat paste no match for the dampness of the winter weather.

So where does that leave us?

Hurricane Sandy has come and gone, providing an object lesson in the vulnerability of critical infrastructure to climate change. I was at a panel discussion at NYU, itself having suffered over 1 billion dollars in damage, and heard how the emergency generators failed at several major hospitals necessitating massive evacuations of patients, many of them critically ill, from the suddenly elevator-less buildings.

Though there was a sense of where the flood waters would impact, it was the social dimensions of the disaster that had been poorly prepared for. According to Kizzy Charles-Gusman (a recent environmental policy adviser to Mayor Bloomberg), Sandy had a disproportionate impact on the elderly, people of color and low-wage workers, who predominantly inhabit the city’s flood-prone public housing complexes of which 402 buildings lost power, water and heat for extended periods of time, which resulted in an epidemic of cold-related illnesses such as hypothermia and respiratory infections, as well as cases of carbon monoxide poisoning in people trying to rig up impromptu heating arrangements with insufficient ventilation. Chronic conditions got dangerously exacerbated in many of the low-income residents who depended on itinerant home care workers, whose visits the storm interrupted. The take-home message was that it was neighbors knocking on doors who provided the best line of defense during the sometimes considerable time spent waiting until the disaster relief agencies could deploy their resources. Climate change, increasingly means we have to get better at taking care of each other, particularly the elderly and the house-bound.

Even without extreme weather, current global warming commits us to a major sea level rise simply due to the thermal expansion of water, contributing at least as much as that to be added by melting ice shelves and glaciers. So it is inevitable New York City and other low lying, coastal areas will get inundated with increasingly regularity and as a result epic and costly engineering interventions will have to implemented that such as moveable flood barriers and relocating and flood-proofing critical infrastructure.

Landscape ecologist and director of the Manahatta/Welikia Projects, Eric Sanderson, suggested ecological solutions to make the New York waterfront more resilient to the effects of climate change, chiefly re-restoring the now largely vestigial salt marshes and oyster reefs that once ringed Manhattan Island, which can soften the impact of storm surges in a self-adjusting, literally rhizomatic way. After a disturbance, the various species of cord grass (eg. Spartina alternifolia and Spartina patens) can redistribute themselves based on their different tolerances for submergence and salinity, forming a self-healing structure that shields the shore behind it. Sanderson pointed out a direct congruence between Manhattan’s mandatory flood evacuation zones and the location of long vanished wetlands, where not surprisingly, the water still collects. As usual, nature knows best and we ignore that at our peril.

Perhaps we can be forgiven for wanting to give things a tweak from time to time though. For better or worse, it is in our species’ nature. Genetic engineering is a case in point. It is controversial, yes, and fraught with danger, not the least of which is the threat posed by big biotech companies patenting the living shit out of everything, recombining what is essentially the earth’s genetic commons and declaring it their intellectual property. The technology to re-splice genes has been around for a good while now and the genie can’t easily be put back in the bottle. So given what’s at stake – and there is a lot at stake – why let big corporations dictate all the terms? There is a small but growing movement of bio-hackers who dedicate themselves to promoting an open-source, democratized biotech. They are educating and empowering ordinary citizens with the tools they need to counteract the hegemonic, capitalistic tendencies of the industry and encourage creative investigations into bio-tech that may not be explicitly utilitarian or commercial, but artistic or otherwise conjectural.

The folks at GENSPACE epitomize this emerging aesthetic and in their funky Brooklyn biolab they offer workshops in isolating, amplifying and re-combining DNA to artists, high school students and just about anyone else curious and patient enough to learn some basic molecular biology and acquire lab skills. By promoting this kind of literacy, GENSPACE includes whole new communities in a practice once relegated to the cloistered labs of the academy and the corporate sector and in so doing democratizes the discourse around this controversial yet epochally significant technological evolution. Though I personally have grave concerns about the release of novel genetic material into the biosphere, the likes of Monsanto have already made that decision for us and we now live in a world where transgenic pollen billows through our air and super weeds erupt between rows of genetically engineered crops, whether we like it or not.

Yet on the other hand, under the guidance of GENSPACE’s Ellen Jorgensen, I was quickly able to learn some basic techniques and sequenced a portion of my DNA, which when analyzed yielded some interesting results:

I carry, through my long chain of ancestral mothers, the H1a3 maternal haplogroup, which originated in the Younger Dryas Cycle – a cold snap occurring between 12,900 and 11,500 years ago that interrupted the general warming trend near the end of the Ice Age. Which means (not surprisingly) that my genetics are deeply and anciently European. But this is just the tip of the iceberg. (Sorry!) If I had run a more comprehensive analysis, (or sent a sample of my spit to some commercial personal genomic testing company, like 23andMe) I could uncover a wealth of nuanced, highly individual information, including my probability of contracting various genetically determined diseases, susceptibility to allergies, candidacy for certain medications and even how much of my DNA has been contributed by Neanderthals.

Clearly this might be useful, not to mention interesting… If I knew I had the genetic proclivity toward diabetes or heart disease, I might keep a closer eye on my diet or even start taking preventative medicines. Yet the larger motivation for me to start learning about genomics is one of basic literacy. As biotech becomes increasingly ubiquitous, it will be imperative for an engaged citizenry to have a basic grasp of its underlying principles, so we can at least filter the signal from the noise at both the Luddite end of the environmental movement and the slick, self-serving communiques of a multi-billion dollar industry.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, genetic processes prove to be an immensely design tool, even outside the test tube. An entire technology of computation has evolved using genetic algorithms, basically simulations that create powerful synthetic evolution machines that can be deployed to solve complex computational problems. I attended a fascinating lecture given at EYEBEAM by the Deluezeian scholar Manuel deLanda, who explained how genetic replication algorithms can be applied to architectural design. For example, the biological principle of heterogeneity occurs when populations of organisms reproduce sexually and shuffle the genetic deck to create occasionally novel outcomes that sometimes confer adaptive advantages to offspring. This principle can be incorporated into form-finding programs such as those that generate solutions to structural problems. These organic algorithms have the benefit of coming up with answers designers didn’t even they were looking for, in as much as they may have been shielded by educational or cultural predispositions. The algorithms can also be set to evolve in the manner of a neural net, interacting with the designer as in: ‘do you like this?’ to refine outcomes iteratively.

Artificial life when it is left to evolve can be quite uncanny, yet when it does, as in this vintage Karl Sims project from the 90’s, one can clearly see that there are some universal principles at work. These simulated beings can evolve and even reproduce but will we ever get to the point where we need to give them rights?