|

|

The Sea and the Desert is a chapter in Henry David Thoreau’s chronicle of his extensive ‘sojourning’ around Cape Cod in the 1860’s.

We might think of rising sea levels and creeping desertification as uniquely contemporary symptoms of anthropogenic climate change but Thoreau noticed them way back in his day, recording with his characteristic eye for detail, a great many meteorological, ecological and human phenomena that together create the shifting territory of the thing we call ‘the Cape.’

This desert extends from the extremity of the Cape, through Provincetown into Truro, and many a time as we were traversing it we were reminded of “Riley’s Narrative” of his captivity in the sands of Arabia, notwithstanding the cold. …. In one place we saw numerous dead tops of trees projecting through the otherwise uninterrupted desert, where, as we afterward learned, thirty or forty years before a flourishing forest had stood, and now, as the trees were laid bare from year to year, the inhabitants cut off their tops for fuel.

Though Cape Cod has been in a state of constant flux ever since it was first bulldozed into place by the glaciers of the last ice age, there is a certain poignancy to its more recent, post-colonial history, as one of the first landfalls of European incursion into North America. The successive human waves that broke upon its shores left their own layers of deposition–the accumulated strata of hopes, ambitions and failures are embedded all over the landscape, if one knows where to look.

Thoreau encapsulated the protean quality of the Cape so beautifully:

The sea-shore is a sort of neutral ground, a most advantageous point from which to contemplate this world. It is even a trivial place. The waves forever rolling to the land are too far-travelled and untamable to be familiar. Creeping along the endless beach amid the sun-squall and the foam, it occurs to us that we, too, are the product of sea-slime.

It is a wild, rank place, and there is no flattery in it. Strewn with crabs, horse-shoes, and razor-clams, and whatever the sea casts up,—a vast morgue, where famished dogs may range in packs, and crows come daily to glean the pittance which the tide leaves them. The carcasses of men and beasts together lie stately up upon its shelf, rotting and bleaching in the sun and waves, and each tide turns them in their beds, and tucks fresh sand under them. There is naked Nature, inhumanly sincere, wasting no thought on man, nibbling at the cliffy shore where gulls wheel amid the spray.

There is still a seething, hissing quality about the place; a sort of fragility too, as if all the quaint human infrastructure, the architectural bric-a-brac of National Seashore information kiosks, the tourist shops and thriving gay bars of Provincetown, the upscale beach houses and black-topped roads could all be washed away with the slightest turning in the weather.

Given my interest in disturbance ecologies, I was thrilled to be offered an artist’s residency at one of the Cape’s oldest houses, at a place called Phats Valley near the town of Truro. I was joined there by my friends and collaborators, Liz Ellsworth and Jamie Kruse of the New School, whose artistic practice focuses primarily on matters geologic and the study of deep time, and who both have had a long term aesthetic engagement with the landscape and culture of the Cape.

We set ourselves a mission of a contemplative nature: to endeavour to capture something of the essence of our locality in its current, Anthropocenic, moment; to attune ourselves to its ephemerality by simply walking, pausing and observing. Our inspiration was the 17th century Japanese poet Bāsho, who set set out on a five-month journey, documented in his poetic chronicle: Narrow Road to the Interior. While traveling, Bashō drew upon and modified the traditionally collaborative haiku practice known as renga, which incorporates sensations of place, events and allusions to literature, history and myth. Renga, in its most basic form, is written by multiple authors who link their verses, building upon each other’s words under the inspiration of the environmental and social contexts of the moment (the trees in bloom, the stage of the moon, and who else is present at the renga party.) At its best renga embodies the impermanence, the ‘this-ness,’ of an instant in time.

Deleuze gave (this) ‘this-ness’ a name, calling it haecceity, from the Latin ‘to behold.’

A season a winter, a summer, an hour, a date have a perfect individuality lacking nothing, even though this individuality is different from that of a thing or a subject. They are haecceities in the sense that they consist entirely of relations of movement and rest between molecules or particles, capacities to affect and to be affected.

A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (with Felix Guattari)

With the inspiration of Thoreau and Bāsho to guide us, Liz, Jamie and I set out under the great blue vault of a magnificent late summer sky to begin what the theorist Jane Bennett refers to as microvisioning, in reference to the way Thoreau practiced his art of engaged observation and deep attention–not an overly probing or systematic scrutiny–but rather more of a perceptual wandering; a seeing without preoccupied looking.

Go not to the object; let it come to you…

(Thoreau’s Journal 4:351)

From our base at the verge of time and space on the margin of Phats Valley’s picturesque salt marsh, we sojourned to various nearby localities, making a daily practice of easing into our immersive awareness, starting our sessions with conversation and tea before we delved into contemplative observation and ultimately, the generation of the renga stanzas. These take the format of (5,7,5,7,7) syllables. .

(5, 7, 5,7,7)

My gaze it returns

To dying rays of sunshine

A vulture circling

In an otherwise empty

Blue anthropocenic sky

(For example)

Liz and Jamie’s long-standing relationship with the Cape complimented my situation of never having been there before, and writing together gave us the chance to meld our sensibilities and subjectivities, our responses to the environment and the material conditions we encountered; both in the perfect individuality of the moment and in the larger geologic and historic frameworks where these moments seem to float. I had just been at the massive (600,000 person strong) People’s Climate March in New York City–a watershed moment in the public acknowledgement that something ought to be done–but what did it all mean? Through renga, I hoped I might get a little closer to some kind of understanding

Our daily practice evolved as a kind of meta-narrative, a record of our pausings, when we made the time to observe and acknowledge the this-ness of a given moment within the multiplicity, or white hiss, of all the other moments, extending through space and time.

We ended our residency with a public renga writing party and shared a lovely afternoon with a group of intrepid poets, who composed the renga with us on large rolls of paper, tacked to the outside walls of the historic Phats Valley headquarters. The whole event is nicely documented here on Liz and Jamie’s blog. Thanks in particular should be given to the residency coordinators Ann Chen and Davey Field of the Nomadic Department of the Interior, who made our residency possible. The house, dating back to the American Revolution, has been in Davey’s family since the early 1960’s and staying there was truly a delight, though when I first walked in, about to spend the night in it alone, I could sense there was some kind of ghost or other (palpable though not visible) presence sharing my abode. As is my custom, I introduced myself to the empty yet somehow electrically charged air of one of the attic bedrooms, and from that point on a cosseting calmness descended and I was able to sleep most soundly. Ghosts very much need to be acknowledged I think, and might appreciate a certain degree of politeness. After all, who knows what it might be like for them having to put up with us clattering around like boors in the overlapping domains of our reality?

Be it the accumulated spirits of the deceased inhabitants or the drifts of plastic waste piling up on its beaches, Cape Cod is all about layers. It is a shifting palimpsest that appears to will itself into being; reconstituting itself out of the products of its own decomposition and perpetually reemerging as the new Cape, out of the shifting, drifting sediments of the old. With its vitality, agency and interconnectivity to the deep, swirling cycles of geology and weather, Cape Cod is truly a hyperobject.

In order to engage such an ephemeral subject at a given instant, we thought it helpful to embrace Thoreau’s concept of ‘incomplete learning,’ an experience akin to what one feels when starting a foreign language, when the sounds and meanings are not yet clear and still largely perceived as an undifferentiated continuum–with the inherent capacity to startle, yet without being subsumed into the banality of explicated meaning.

‘Not until we have lost the world do we begin to find ourselves’

(Thoreau, Walden 171)

Jane Bennett makes reference to this non-judgemental, rather Zen-like practice of observation, in her 2002 ‘Thoreau’s Nature: Ethics, Politics in the Wild,’ where she builds a convincing case for his surprisingly post-modernist tendencies.

mineraloids The Phats Valley house and its immediate environs exist as a kind of microcosm for the cycles of ebb and flow, erosion and sedimentation that so define the ‘Cape-ness’ of the Cape. The salt marsh is bisected by an artificial ithmus– the abandoned causeway of the Cape Cod railway, now the domain of sombre pitch pines and scraggly sumachs. In its rubble, I found anthropocenic mineraloids– fragments of slag, coke and brick constituting the geologic stratum of a once thriving Steam Age civilization that existed here during the 19th century. The quaint house, archetypical Americana, with its prim clapboard and gnarled, rustling trees, now seems a world away from the spectre of machinery. The long driveway floods during the higher tides, adding to the sense of splendid isolation.

Yet the view from the front door, which now looks out over an olive-coloured expanse of soughing cord grass and wheeling marsh birds, was once very different; the railway passed by just a few feet away, and I can imagine the chugging, clanging locomotives vibrating the windows of the parlour, backlighting the curtains with a roiling orange glow as they pulled their squealing train cars on into the magnetism of their destination.

That is all long gone now of course–another layer obscured by more recent sediment, continually accreting. The topmost strata is unmistakable in that it contains massive inclusions of discarded plastic, the most ubiquitous material of our age. In the relatively short time of its existence, plastic has spread throughout the biosphere, substantial parts of which, particularly in marine environments, can now legitimately be called the plastisphere, as organisms have already adapted to the problematic material by colonizing it and breaking it down into an even greater multiplicity of substances potentially harmful to man. Indeed, Plastics “R” Us!, as water-soluble plastic chemicals like bisphenol A (BPA) and flame retardants already circulate in all of our bloodstreams.

At Phats, the plastisphere is most visible in the zone of flotsam deposited at the high tide line. Plastic dominates this territory in a surprising variety of material expressions, creating an overall aesthetic experience that borders on the beautiful or the repulsive, depending on what frame of mind one is in. I include some photos of these happenstance assemblages at the start of this post.

Poking around those drifts of discarded polypropylene, polyethylene, styrene, vinyl, polycarbonate and nylon, I wondered what will form the stratum of the next geologic age? Will it be the ashes of human extinction that mark the dawn of the post-human, the way the K-T boundary delineates the quick and brutal end of the dinosaurs? Or will we be someday heralding the age of the neo-human, having somehow morphed into a species with greater sensitivity to the material realities of the planet on which we evolved.

Whatever will come next?

Whoever?

dwarf birches and tundra  suddenly – reindeer!

The morning broke grey and brooding outside the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station and after a quick breakfast, we were on the trail, hiking up Saana Fjell, guided by Erich Berger of the Finnish Bioart Society. The idea was to familiarize ourselves with the geology, ecology and cultural history of the vicinity so we could dive into our research plans as soon as possible.

The Australian bio-hacker, Oron Catts had already been here for a week to do some scouting for his group’s ‘Journey to the Post-Anthropogenic’ project. They planned to perform a comprehensive bio-archeological survey of the crash site of a German Junkers 88 bomber that came down on Saana in 1942, which included a metagenomic analysis of the plane’s debris field and a recreation of the crash trajectory using a remote-controlled drone.

debris field It wasn’t long before we passed the tree line where the mountain birches gave way to an expanse of open tundra sweeping out before us in a swath of russet heath and exposed rock, with quivering patches of silver cloud here and there snagged on the crenellations of the topography. As if on cue, a small herd of reindeer appeared over the crest of a nearby hill and galloped across our field of view, cocking their heads as they past us and then just as quickly melting into the gloom of the opposite horizon. It is hard to judge distances here in this cold desert. An unusual rock formation in the distance might be small and quite close by or enormous and very far away.

I felt for a moment as if I had been transported back to the Pleistocene, as the landscape I was looking at was what much of Europe and North America would have been like at the end of the last Ice Age, though (other than the reindeer) there wasn’t any of the charismatic megafauna such as the woolly mammoth and the cave lions I would have had to concern myself with back then. Semi-domesticated, reindeer have sustained the local Sami people since ancient times and they are of the few creatures (other than snails) to manufacture the enzyme lichenase, enabling them to survive on lichen during the winter months.

How this delicate ecological balance will be affected by climate change is unclear but to my mind it doesn’t look good. Lichens exist in fairly specific temperature and humidity conditions and in Kilpisjärvi many are symbiotic with the birch trees, themselves a cold-dependent species. A continued warming trend in this region is bound to mean diminishment of suitable reindeer habitat. This has already occurred in North America, where the closely related Woodland Caribou has steadily disappeared from the southern portions of its range.

Standing in the middle of this iconic subarctic landscape, it is hard to imagine rapid changes occurring. For thousands of years, the processes shaping it have been gradual and incremental – the slow scouring of glaciers advancing and retreating, the infiltration of frost with its insidious heaving and splitting, the seasonal flows of meltwater into the lakes and rivers. The cold accentuates the sense of Deep Time here. Rocks dragged by ancient ice flows sit solemnly in place as if they stopped moving only yesterday. The sparse, slow growing vegetation is no match for the overwhelmingly geologic feeling of the place. Even minor disturbances stay visible for centuries.

But add even a small degree of warming and there would be potentially huge changes. Vegetative growth would ramp up, allowing trees to flourish in areas that were once windswept barrens. It is easy to imagine the slopes of Saana darkening as the Scotch Pine (Pinus sylvestris), now found only intermittently in the Kilpisjärvi area but quite common further south, finds conditions more suitable to it and becomes a dominant species. True tundra and the flora and fauna that depend on it could disappear from the area entirely.

lone Scots pine Fast-forward a little further and there could be a whole host of new species that find the once frigid environs of Kilpisjärvi newly tolerable. A good many of these are likely to be weeds, which thrive on man-made disturbance. Investigating the grounds around the research station, I soon found a small clump of English plantain (Plantago major) a cosmopolitan weed, dubbed the ‘white man’s footprint’ by North American First Nations, who noticed it growing wherever European colonizers had disturbed the original ecosystem. The humble plantain is just the beginning. I predict that larger weed species will soon be gaining a foothold at Kilpisjärvi; their seeds imported on tire treads or blown in with the wind.

I wondered how it might look here when Ailanthus altissima, a tree variously known as the ‘Ghetto Palm’ or ‘Tree of Heaven,’ moves into the Finnish subarctic. Originally from China, Ailanthus is exuberantly invasive, and has already moved into ruderal (ruin) ecologies throughout the world without any signs of stopping. This tree has the astounding ability to feed off concrete, allowing it to thrive in cracks in pavement, the roofs and facades of under-maintained buildings and pretty much any other place its myriad seeds are able to lodge themselves long enough to germinate.

Ailanthus trees As the global south becomes uninhabitable due to increasing drought, wildfire and relentless heat, it isn’t hard to imagine a newly temperate Kilpisjärvi becoming a major magnet for climate refugees, human and non-human. Higher annual temperatures, as well as attracting different flora and fauna, could make the cultivation of cereal crops a possibility and perhaps other kinds of intensive agriculture, now more characteristic of Central Europe. This could transform the wild, transhumance landscape into a ‘Kulturlandschaft,’ the subarctic wilderness giving way to ploughed fields, perhaps even orchards. There might be a property boom as the open range lands once suitable only for reindeer husbandry become hosts to cash crops and housing estates. The effect on the traditional Sami lifestyle would be incalculable.

A climate-changed Kilpisjärvi would be a kind of ‘hyperecology’– a co-mingling of adaptive, cosmopolitan weeds, perhaps a few resilient local organisms and a steady in-migration of biota from the south. Outside the national parks and reserves, post-climate change nature will have even less of a free hand. There is massive industrial development afoot for Lapland, particularly mining and its ancillary industries which threaten to blight vast tracts of the relatively pristine landscape with open pit mines, tailings ponds and processing infrastructure, which, as well as inevitably introducing all sorts of pollution will create a new terrain vague of slag heaps and factory wastelands. These ‘brownfields,’ ubiquitous in much of the industrialized world are the preferred habitats of the globally distributed ragamuffin flora: Ailanthus, Buddlea and Robinia, which find the toxic and impoverished soils to their liking.

Industrialized, intensely cultivated and densely populated, the Kilpisjärvi of the not-to-distant future might look strangely familiar to any present day resident of a more temperate latitude. Yet what has been predictable there for so long will soon become much more extreme. We may all find ourselves moving north.

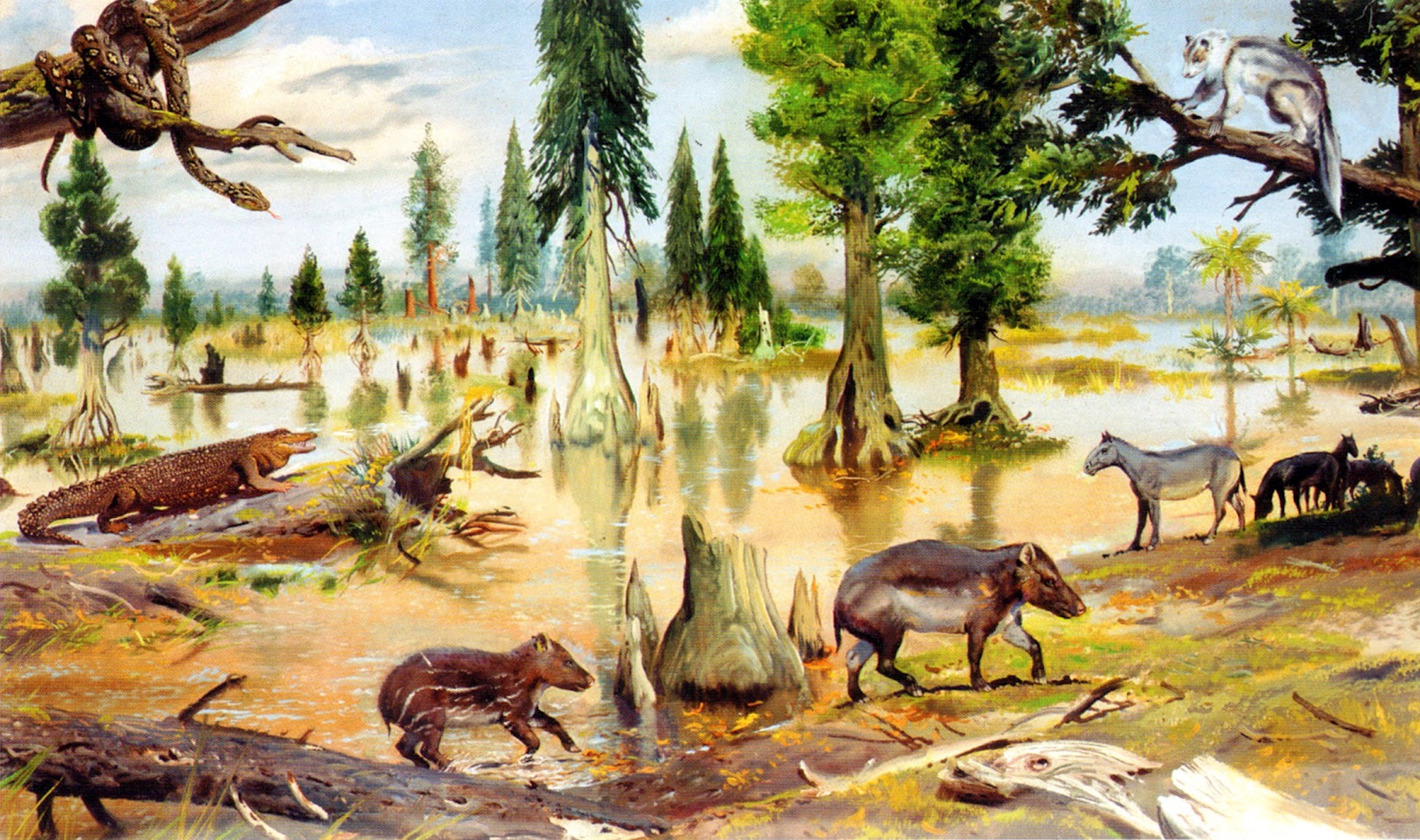

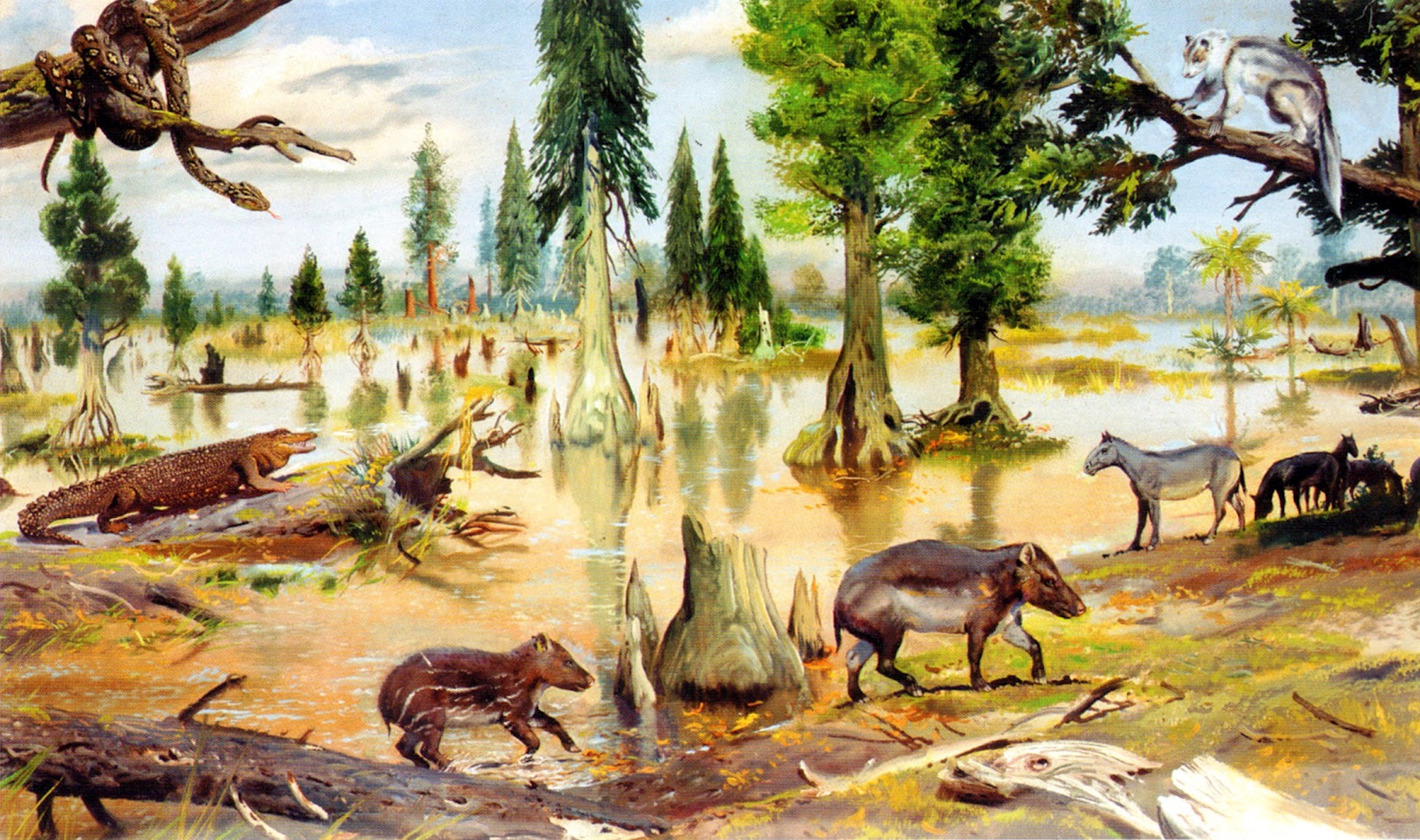

But climate change isn’t likely to stop at this arbitrary point. The heat will likely continue to build, especially if mankind continues dumping carbon into the atmosphere and particularly if the much feared ‘runaway greenhouse’ effect kicks in. What then for Kilpisjärvi? The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum that happened some 55 million years ago gives us a clue. In those days, the weather north of the Arctic circle was sultry and humid the year round. In addition to the Sciadopitys trees I described in my previous posting, vast swamp forests of Metasequoia and Taxodium spread out across the far north of Eurasia and North America, with turtles and crocodiles plying through the black water and mire. It would have resembled the bayou country of Louisiana or subtropical China, with snow and ice pretty much non-existent, a far cry from the frigid Kilpisjärvi of today, which can be icebound 200 days a year.

Eocene landscape Northern regions are well on track for a repeat of these subtropical conditions according to the most agreed upon climate change models, which predict an up to 4 degree Celsius rise globally by the end of the century, with a strong likelihood that changes in high latitudes will be more extreme. Though the biota will surely be more impoverished than it was in the Eocene, not having had anywhere near as much time to evolve, an anthropogenically tropical Lapland would be a mind-boggling yet disturbingly real possibility.

Though our species’ effect on climate can (and will) precipitate far-reaching changes in areas like Kilpisjärvi, there are many planetary processes playing out over which we have no control. The evolution of biota over Deep Time is as much happenstance as forward movement, with periods of great flourishing such as the infamous ‘Cambrian Explosion’ interspersed with ‘reversal’ or mass extinction, either organically or extraterrestrially engendered, which often obliterate whole classes of once dominant organisms and provide opportunities for minor ones to come out of the wings.

Past instigators of mass extinction have included: asteroid impacts, widespread volcanic eruptions with concomitant ocean acidification, even the evolution of photosynthesis by cyanobacteria, which released the toxic gas oxygen into the atmosphere to the detriment of the once dominant anaerobes. Any and all of these scenarios will likely play out again somewhere in the fullness of Deep Time, but barring the elimination of all life on the planet, it is worth speculating on the impact such upheavals would have on the vegetated landscape.

For example, what would happen if flowering plants, also known as angiosperms, dramatically declined, perhaps taken out by some pandemic or selective evolutionary pressure? They’ve really only been common since the Cretaceous and it isn’t hard to imagine Kilpisjärvi’s abundant so-called ‘lower’ plants – mosses, club mosses and liverworts, moving into the vacuum and attaining gigantic proportions, as was the case during in the coal swamps of the Carboniferous Period.

Neo-Kilpisjärvi with giant club mosses A reduction in the availability of sunlight due to volcanic ash or widespread dust storms could have equally bizarre consequences. With green plants and algea in decline because of the challenge to photosynthesis, there would be a selective advantage for fungi, which might take over Kilpisjärvi forming bizarre, colossal structures as they did during the Devonian Period, some 400 million years ago, and again during the mayhem of the Permian mass extinction. Whether our own species would survive under such extreme and alien conditions is an open question, but life of some sort is almost certain to find a way. Perhaps fungi will regroup to form the planet’s supreme intelligence. Some would say, they already have!

It is this last point that gives me a vestige of hope. We Homo sapiens are a problematic creature, a classic, invasive species that thrives on disturbance, tends toward monoculture and displaces competing biota from its habitat. Yet in the overall scheme of things we are likely to be a transient phenomenon. We will either precipitate our own extinction, (and if the surviving ecosystems of the planet could sigh in relief, they surely would!), or we will find a way to live within our ecological means and develop a more equitable arrangement with the fellow denizens of the biosphere. My stay at the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station offered me the ideal vantage point to consider this conundrum. What we are in now is not so much of a ‘watershed’ moment but more of a ‘timeshed’ moment!

Neo-Kilpisjärvi with giant fungi

Vancouver Island highway scene At this ardently bright juncture of the year, there is something quite delightful about gazing up into the cool, rustling canopy of overhanging trees. It is a very deep memory for me. I must have been an infant, lying on the back bench seat of my parents’ old Buick, gazing up through the rear window at the dark tunnel of foliage billowing overhead, flashing here and there with orange bursts of interpenetrating sunlight. The dust from the road was starting to smell like the softer evening version of itself and the roadside insects, cicadas probably, hissed in their enormous, invisible numbers.

In my recent journeys between England and Canada, I have been struck by the contrast in attitudes toward what one might call ‘arboreal heritage’ between the two places. When driving on Vancouver Island I am inevitably torn between throwing up and crying whenever I see, as I almost always do, some of the last old growth Douglas firs (Pseudotsuga menziesii) getting hauled down the highway on some logging truck. Their rate of felling has been accelerated recently by a growth in demand from overseas, particularly Chinese, markets and the provincial government’s stupendously short-sighted decision to relax restrictions on the exporting of raw logs.

Each one of these ancient trees is a monument to the passing of centuries, a lynchpin around which complex ecological processes have evolved and yet we are losing the last primeval stands right at this very moment. To see one of those loaded trucks is like witnessing the carcass of a blue whale or a rhinoceros trucked off to a dog food factory but what more is there to be said? We have pointed our fingers yet the market economy has triumphed and the trees continue to fall. Soon all there will be left is a lingering sense of shame until that too eventually disappears. Outside a few relic specimens that happen to find themselves inside parks, the ancient fir groves of Vancouver Island will soon be obliterated. The Island Timberlands company continues to be a key player in this campaign of ecological extermination and is specifically targeting the large old trees on its vast private holdings to service an international market growing all the more lucrative as the global supply of first growth trees plummets.

this linden (lime) tree has been coppiced since at least the 13th century! While British Columbia has been embarrassingly and heartbreakingly remiss in its protection of Vancouver Island’s ancient firs, there are pockets of silvicultural enlightenment elsewhere in the world that can restore one’s faith in humanity. Last month Ruth and I spent a memorable afternoon at the Westonbirt Arboretum and got introduced to some of its innovative programs by director Simon Toomer. It may sound odd, but one of the highlights of our tour was seeing the manifold stumps of a recently harvested lime (Tilia sp.) tree, which has been harvested using the coppicing technique since at least the 13th century. The tree itself, which has spread out into about 60 individual stems, could be over a thousand years old! Coppicing (periodic cutting from regrowth regenerated from stumps or ‘stools’) is an ancient technique, suitable for a variety of mostly broadleaf trees, which paradoxically causes them to live much longer than if they were allowed to grow uncut. The practice periodically opens up parts of the forest canopy, allowing for an influx of light and a host of species dependent on brighter conditons, which enhances diversity in the forest, without massacring the entire structure over a large landscape as is done during industrial clear cutting. In British Columbia, it would definitely be worth testing out large-scale coppice management of Big-leafed maple (Acer macrophyllum) and Red Alder (Alnus rubra), both of which are capable of rapid regeneration from stumps and which have the potential to produce a range of sustainable wood products.

Westonbirt is also engaged in pioneering research on how forests will be affected by climate change and have initiated a series of long term trials of trees, hailing from a spectrum of locations, from the southern to northern parts of their present day ranges. If conditions continue to heat up, it is likely that trees evolving in more southerly latitudes will increasingly thrive within the British landscape, while more cold-adapted ones will only do well at higher latitudes and altitudes.

Back in British Columbia, I am beginning to draw similar conclusions. Though still in its early stages, the initial results of my Cortes Island ‘Neo-Eocene’ project indicate that some tree species now native to more southerly latitudes, such as Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and Metasequoia (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) might actually grow faster under West Coast Canadian conditions than varieties currently prescribed for re-forestation, such as Western Red cedar (Thuja plicata). The difference is likely to intensify as northern climates continue to heat up. Climate warming is already causing massive mortality in northern populations of the native yellow cypress/cedar (Cupressus nootkatensis), because spring snow cover is no longer thick enough to protect their delicate roots from late frosts.

The premise of ‘Neo-Eocene’ is that we need to examine longer, more geologic time spans for guidance on how ecosystems might deal with the rapidly unfolding effects of anthropogenic climate change. During the Eocene Thermal Maximum, some 55 million years ago, taxa such as Sequoia, Metasequoia and Gingko, which are now extremely limited in natural distribution, did in fact range far into northern latitudes; so it makes sense to experimentally reintroduce them, especially to areas where the extant forest has been compromised by industrial logging or climate-change induced die-offs. Our concept of what is considered ‘native’ needs to be rethought, and we’ll have to expand our definition to encompass organisms that have been ‘prehistorically native.’ So bring on the Giant Ground Sloths! If only we could!

Apropos of the topic of ‘Deep Time,’ I have been invited to Finland this September to participate in the Field_Notes – Deep Time residency in subarctic Kilpisjärvi Finland. Along with the Smudge Studio folks and a bunch of other amazing people, I’ll be considering how developing a more ‘geologic’ perspective might help assess our trajectory into the deep future. As the world heats up again to levels seen only in the geologic, pre-human past, how will we cope? How long will it take for a subarctic place like Kilpisjärvi to feel like Lisbon or Lagos? Will more southerly latitudes, once temperate and agriculturally productive, become thermally uninhabitable? Will climate refugees, human and non-human, flood into the formally frigid northland? How might the northern biota adapt? Or can it? Anyway, I am endlessly excited.

Davidia tree in Wiltshire Another refugee from deep time is the wonderfully flamboyant Davidia tree, which dates back all the way to the Miocene, when it was much more widely distributed. Miraculously, a few groves somehow survived the intervening millennia deep within the gorges of Szechuan China. The tree with its magnificent, floppy white bracts, which some liken to handkerchiefs or doves, caught the attention of a French missionary, Abbé Armand David. He sent some dried samples back to Europe and a botanical sensation promptly ensued. It wasn’t long before a plant hunters from England and the United States were dispatched to what was then a very remote area, charged with collecting Davidia seeds for cultivation. In the Davidia’s case, this proved to be a boon for the global population as there are now fine specimens of the tree flourishing in parks and gardens throughout the temperate zones of the world, thanks to those early batches of seed. Davidia, as is the case with Metasequoia and Gingko are considered vulnerable in their native habitat, and it is only through their widespread cultivation outside the small territories in which they still naturally occur that their future remains assured. Yet who knows? These curious and obscure trees might contain within them a genetic willingness to reestablish themselves in vast swathes of the northern hemisphere, as the climate of the distant geologic past becomes the climate of the not so distant future. Here is a picture of the biggest Davidia I have ever seen. It was in full, glorious bloom, when I visited the the grounds of a lovely Wiltshire property, owned by the Guinness family. Judging by its size, this specimen seems likely to have been one of the first ones propagated – an ambassador of sorts from the distant geologic past that once again has a role to play in the beauty of the wider world.

a flurry of doves or handkerchiefs!

|

|