check out Baudrillard’s

L’esprit du terrorisme [The Spirit of Terrorism]

for a reality check on 9/11.

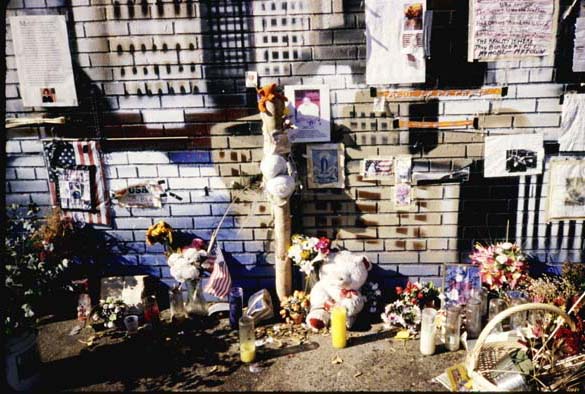

near Ground Zero

impromptu shrine, Lower East Side

|

||||||

|

check out Baudrillard’s

It’s the end of summer and I am sitting in my car, waiting for a ferry and looking at a limpid, grey sea. Big black vultures are spiraling lazily above me, riding the thermals, wafting up from the tarmac, on their ragged wings. They are seeking death with the quiet urgency of those who know its inevitability, traversing through the vast columns of moving air that define their universe, with nonchalant ease. It will come, and they will feed.

I’m re-reading Martin Bax’s The Hospital Ship and am once again struggling with the great nagging questions of “Are we fucked?” and “How do I get myself organized now that summer is over?” Bax’s book posits a hospital ship in some period in some parallel reality that is plying the seven seas, in the middle of a vast pandemic of violence. People are slaughtering each other everywhere (literally crucifying each other), and piling up the casualties on the quays. Nobody really knows what’s going on and the news coming in by radio to the ship is disjointed and contradictory. The reports are all transcribed on paper and pinned to a wall but sadly:

I see in this passage an uncomfortable parallel to my own struggle with personal organization. – Incoming bulletins frequently fly off of the metaphorical boat and on into the sea, and I start to lose track of the big picture. I manage to snatch a few bulletins from the air as they careen by, and this becomes the basis for my blog, but mostly they wind up floating on the grey waves, gone forever. What I am managing to piece together, doesn’t look too good. Like the world described in ‘The Hospital Ship’, I’m beginning to think we are fucked.

Bax nailed it, and many of us increasingly feel it. The constant lump in our throats, the shortness of breath and the deep sadness. The constant attempts to pin down some transient bits of reality before they evaporate into nothing. At least we have our blogs . . . Perhaps total collapse HAS already occurred. Some ecologists place the point of no return somewhere in the 1980’s. It has to do with the collapse of Antarctic iceshelves of an order of magnitude never seen before in human history. Maybe we should feel somehow strangely liberated. At least we have certainty. . . But how do I organize my handbasket, as I careen in it towards hell? I think about this all the time. . .

My friend Laura has given me new hope in that direction. She has shown me the brilliant work she is doing using Plone and Zope– prodigious open source content management systems that seem to hold great promise. The websites that she creates with these tools cool the fevered brow of my organizationally challenged mind with reassuring rows of tabs and elegant, transparent, immediately comprehensible architecture. I must learn how to use these tools soon, before I descend into deep entropy. It is so easy just to drift . . . and As a result, I can’t help feeling a bit twitchy. Perhaps its my ‘R’ complex. ‘R’ for reptile, the lizard mind that straddles just above the core of my neural chassis. Lizards appear to experience things more or less directly, without the burdensome freight of intellect. They process their perceptions, predominantly with their ‘R’ complex. This pre-lingistic pattern-recognizing mode can get deeply fried by the constant flux of bulletins pouring in from the cerebellum. The world’s highest paid executive coach , told me (how this happened is a long story, best saved for another posting) that I “think too much”, and maybe he is right. Maybe my sense of ‘self’, is getting in the way of happiness. But somewhere in there beats the heart of a lizard. And lizards have lived through a few mass extinctions . . . Recently, after feeling a little overwhelmed, I took off all my clothes and jumped into the ocean, hoping it would help me ‘re-boot’. This in itself is not as radical as it sounds, in the cultural Galapagos which I call home. Clothing is optional at the beach. In fact, there are some people around here whom I don’t recognize with their clothes *on*. The water was cold and I soon emerged to bask, naked on a rock ledge. Somewhat zoned, I let my gaze fall vacantly on the crinulations and tessellations in the rock and was startled to come upon a tiny eye winking at me from the darkness of a nearby crack. Was it my disembodied lizard mind? It was a Northern Alligator Lizard, engaged in the same thermotropic behaviour as me. Basking. A lizard at the northern extreme of its range. At this latitude they have adapted to the cold by becoming live bearing, ensuring the survival of their heat-loving young by sitting for hours in the weak northern sun. So we had a moment of poikilothermic bonding, and I tried to cast my mind back to what I might have been thinking during the Triassic. I moved my head and the lizard skittered away. I guess it panicked . . . .

Northern alligator lizard, Vancouver Island, British Columbia

I suppose it is inevitable for the time of year. Perhaps it is the sense of the long summer waning, its once endless expanse of days, now finite and running out like grains of sand in an hourglass. Since childhood, I have experienced late August with a sense of foreboding. The shortening days and lengthening afternoon shadows were inevitably the unmistakable harbingers of irrevocable and systemic changes. The reality of the upcoming school year would suddenly loom like an oncoming ship, emerging from the quiescence of a fog bank. The languidity of summer seems to evaporate overnight into sharp little crystals of urgency. The nightly chirping of crickets is a little more frenzied now, signaling perhaps the end of unstructured time – at least for this year. The end of the endlessness of the season of the sun. Like it or not, the universe is shifting its gears. We must choose between frisson and dread. Somewhere a demon figure is pulling the levers. Click Click. In the clear warm night skies, Mars has been shining like a pulsing red beacon, the closest it has been to the earth in 65,000 years. Mars is after all, the god of War. The last people to have seen it this clearly were the Neanderthals, and they went extinct. A recent trip to the idyllic seeming little town of Courtenay BC and I am approached on three separate occasions by sad looking middle-aged women, begging for change. Middle aged and formerly middle class, they have somehow fallen like dried leaves from the withering bough of the bourgeoisie – the walking wounded in the Class War. Twenty years of economic brutalism have become so deeply entrenched, that this no longer seems remarkable – even in Lotusland. After all, the fear of winding up homeless, keeps a lot of low-income workers from fighting for better wages or working conditions. Keep poverty visible and you have a very effective form of social control. It keeps the cost of labour down. Brian Eno, the godfather of ambient music writes a wonderful review of John Stauber’s Weapons of Mass Deception, in the Guardian. Eno, who brought us the seminal 1978 Music for Airports is now helping to deconstruct the ubiquity of ambient American propaganda. This is truly wonderful and dementedly mimetic. I continue to admire him greatly. Renana Brooks writes in The Nation about the use of studied ‘empty language’ techniques and ‘negative frameworks’ in George W. Bush’s speeches, to create an ambience of learned helplessness and inevitability in the minds of the American public. I remember once, (years ago, under the influence of some hallucinogen), suddenly and viscerally appreciating the interplay of flows, chaos and turbulence in the boiling gray sky of a Toronto spring. This connection never left me. It’s easy once you open your mind to the large scale patterns. Deep inside, we’re wired for it. We can read ambience. Outside I see the gray skeins of an oceanic front scudding across what has, seemingly forever, been a painfully white- blue sky. It might be the first rain in weeks. . . One of the odd exigencies of living on the coast of British Columbia, is the moderating effect of the Japan or Kuroshio Current (the Pacific counterpart of the Gulf Stream), on our climate. While we are at 50 degrees north in latitude, (4 degrees north of Quebec City), it is possible to grow figs here. Several of them are ripening on a branch outside my window, where they look incongruously tropical against the backdrop of northern conifers.

Late summer is the season of moths. Every electric light left on at night seems to attract legions of them, relentlessly battering themselves to death against the bulb, shedding the fragile powder that covers their wings as they commit their tiny scorching suicides. Obsessively beguiled by the blinding brightness, it seems they just can’t stop themselves. Does any moth ever ask itself, “Why am I doing this?” My old friend Neil recently reminded me of my favorite moth of all – The original 1960’s Japanese monster movies were all about Japan’s loss of innocence as the first nation state casualty of the nuclear age. Godzilla himself, was a transparent trope for America – big and goofy, smashing up Japanese cities and withering the landscape with his radioactive breath. But nevertheless, he was kind of cute. Like moths flapping at the window of a night-time kitchen, my tribe of WiFi enthusiasts in rural British Columbia clusters and presses against the side of a government building seeking proximity to a high speed data pipe. We bask in its flux of 802.11b, which like nectar feeds our ever increasing appetites for large downloads at high speeds.

WiFi Enthusiasts outside a rural British Columbia government building When the weather is hot, the sky scintillatingly blue and the air throbs with insects, I inevitably find myself on a road trip. While on a recent drive from Vancouver, I found myself musing about the many other summer road trips I have been on. There is something exhilarating about hurtling through a vast summer landscape in a speeding car with the hot air blasting through the windows like a hair dryer and the infinite sky so intensely blue that it seems black around the edges. I especially like to record the passing roadside landscapes with a movie camera and later hunt for images that I might have missed. A lot can happen in a thirtieth of a second.

Hanford Nuclear Reservation Several years ago I found myself driving to Idaho via Eastern Washington to help Ruth do research on potatoes for her book, All Over Creation. I suggested we detour past the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, which has been called ‘The Chernobyl of North America, to try and get a closer look. In the distance, shimmering in the heat haze, we saw an ominous set of military gray buildings set on the arid, sage brush covered banks of the Columbia river. The vast tawny rangeland between the highway and the nuclear reservation was ringed a security fence on which ‘do not enter’ warnings were conspicuously posted. Since its inception in 1943, Hanford has been contaminated with “billions of gallons of radioactive waste” including plutonium, the most deadly substance known, which has been simply buried or is leaking into the ground from deteriorating metal tanks. Hanford was America’s first large-scale nuclear materials production site. The plutonium used to bomb Nagasaki was processed here and later was used to arm America’s Cold War nuclear arsenal. The people living down wind from the Hanford site, (who call themselves “the Down winders”) have sky-high rates of thyroid cancer and a resultant penchant for turtle-necked sweaters. Ironically, this toxic Armageddon has become a wildlife paradise, supporting what National Geographic calls one of the “finest examples of shrub-steppe habitat” left in the Columbia basin. The Hanford Site is home to mule deer, elk, coyotes, badgers, rabbits, skunks, bald and golden eagles, herons, ducks, ground squirrels, several species of mice, lizards and three species of snakes. There are also many species of rare plants. Some are endemic which is to say that they are found nowhere else in the world. A 1994 study covered only 30 percent of the Hanford Site but found 56 new populations of rare plants and discovered a completely new Lesquerella species. The 1994 study also found 205 species of birds on the Hanford Site, including 31 species of special concern, 72 species considered rare, and 9 species never before documented at the Hanford Site. Close to 1,000 insect species also were documented, including 19 species new to science and 200 species new to Washington State. Why is there such astounding biodiversity in this toxic wasteland? It appears that for the survival of natural ecosystems, the absence of human beings more than makes up for the radioactive toxins that have been left behind by us. WE are the most powerful toxin. I riffed on this a bit in a posting on the resurgence of wildlife in the Chernobyl area, a while back. Do we need to protect endangered species by dumping radioactive wastes in their habitats to keep humanity out? That is a truly scary thought! But this is the kind of thing that creeps into my brain just before heat exhaustion sets in. Of course there is always taxidermy. One of my most idiosyncratic pleasures on long road trips through the North American heartland, is to seek out little private museums where people exhibit their moth-eaten collections of stuffed animals and natural history curios. On the same trip, we stumbled upon one such little operation on a back road in the roasting sagebrush steppes of southern Idaho. The museum owners had some deep lava tubes caves on their property, which you could explore for a couple of dollars- well worth it as a respite from the withering heat. Upon exiting the coolness of the lava tube, we entered the run-down museum, which was full of dilapidated taxidermy, animal bones, and most endearingly, an egg collection.

As I understand it, poisons such as arsenic were once commonly used to preserve animal remains used for taxidermy and pose a real threat to museum curators working around them even to the present day. In fact there are taxidermists who have died of arsenic poisoning. Maybe nature is trying to tell us something.

When does landscape become art? This is something I am asked all of the time about my own ‘botanical interventions’. Over time, vegetative landscapes lose some of the aura of the artist , gardener or horticultural dramaturge and develop a life of their own. But when maintained, they undeniably resonate the aesthetic sense of their creator. I love driving around the suburban periphery of Vancouver, which is in many ways a city of demented gardens. The lysergic rampancy of vegetation engendered by the rain forest climate butting incongrously against the banality of the cookie-cutter architecture often makes me think that I am on another planet. Vancouver is a city that labours under the burden of the thousands of failed utopias, projected onto it by everyone who gets sucked into its humid gray vortex. It is the end of the road, the end of the continent – the terminal beach. Everyone seems to be looking for something – some desperately. Is it paradise which they seek? The junkie prostitute with the bleeding legs, scraping manically at the dust with her fingernails in a Downtown Eastside alleyway is looking for it. The Kitsilano professionals are looking for it also, fleeing up to Whistler in their gleaming metal losenges of exquisite German automotive engineering, slurping latés with the top down. But it is in their gardens that I think many Vancouverites come closest to finding what they are looking for. Or rather, it is in the garden that one can create in vegetatitive microcosm one’s own version of paradise, reflecting hopes, aspirations and nostalgia for distant times and faraway places. Vancouver’s moderate climate and abundant rainfall enable every suburban tract to serve as a protean utopia, ready to be coaxed into any vegetative possibility. Chinese windmill palms, Scottish heather, Californian sequoias, Italian figs and Japanese flowering cherries all compete in a crazy botanical cornucopia to colonize the tabula rasa left by the clearcutting of the ancient Douglas fir and western red cedar rainforest that once covered the city. These botanical mammoths exist now only in relic form- a few stragglers in the centre of Stanley Park- solemn reminders of the now reversed figure/ground relationship between the extirpitated natural ecosystem and the ‘Kulturlandschaft’- the landscape transformed by human activity. Simon Schama has an interesting take on this figure-ground dynamic between culture and nature in his Landscape and Memory which tracks the history of our relationship to landscape by mirroring it in our relationship to art. Viewed in their totality, Vancouver’s suburban gardens recede into our “optical subconscious” as we travel through the neighbourhoods, flavouring our journey but not overwhelming us with ideology or didacticism. Yet the dialectic of class and identity lurks beneath the seething shrubbery and the verdant turf. For example, working class immigrants from China often dispense with backyard lawns altogether, upon setting up house in Vancouver. Unburdened by the now diminutized North American notion of living in ersatz 18th century English manor houses, set amid minion-tended greensward, they grow bok choi, garlic chives, Chinese wolfberry and bottle gourds right up to the back door. These productive kitchen gardens are a testament to Confucian ideals of practicality, self sufficiency and economy and the landscape thus created is unapologetically Guangdong- not Giverny. Italians-Canadians drink their Grappa under carefully tended bowers of grapes and figs, the nostalgic leafy architecture of a half-remembered bacchanalia, transplanted from the ancient sun-soaked earth of the Mediterranean to the rainswept patios of Burnaby. And then occasionally, very occasionally, somebody creates a landscape so utterly idiosyncratic that it transcends simplistic analyses. So here it is:

(East Vancouver landscape at Kaslo and East 7th) All day, I’ve been listening to Stereolab’s ‘Cobra and phases group play voltage in the milky night’ and driving myself crazy doing business analysis spreadsheets as part of my cool ‘sustainability’ MBA curriculum. In the midst of the endless banality of the number streams come some interesting insights. Are you autistic? do you have ADD? Some of my readers have been requesting this Guardian link. (you know who you are… after this test, you’ll know even more!) The on-line test can be quite revealing. I’ve been hanging out with our friend Nancy Kates who finished a film this year called Brother Outsider – the life of Bayard Rustin. This is a brilliant film documenting Rustin, the openly gay African-american activist and advisor to Martin Luther King, who was more or less written out of history. Nancy and I spent quality time playing with baby chicks and watching Chris Marker’s 1992 conceptualist film The Last Bolshevik. Marker is basically the closest thing you can get to a ‘blog filmmaker.’ The film is a beautiful reminiscence on the dead Russian filmmaker, Alexandreovich Medvedkin and his role in the Agit Prop trains that once traveled across Russia filming the proletariat, processing the films in special mobile darkrooms and screening them back to the very people that were in them. Agit prop trains were so advanced and (anasynchrostic) for the premodern historical moment (circa 1918) in which they were used, that I still can’t quite wrap my head around them. Dziga Vertov was heavily involved in these Agit Prop trains also and kinetic montages of trains featured prominently in his films. |

||||||

|

Powered by WordPress · Atahualpa Theme by BytesForAll |

||||||