neo-eocene

With the record-breaking heat wave that is currently withering Southern BC, I am starting to wonder just how hot it’s going to get when climate change really starts kicking in. The temperatures we suffered through this week made it feel like we’re already well on our way. Some estimates indicate that our planet might be on its way toward a thermal maximum not seen since the Eocene era – some 55 million years ago. Back in those days, palm trees and alligators flourished as far north as Alaska and the Canadian Arctic. Much of what is now British Columbia was cloaked in a warm temperate forest, far more biologically diverse than what we have today.

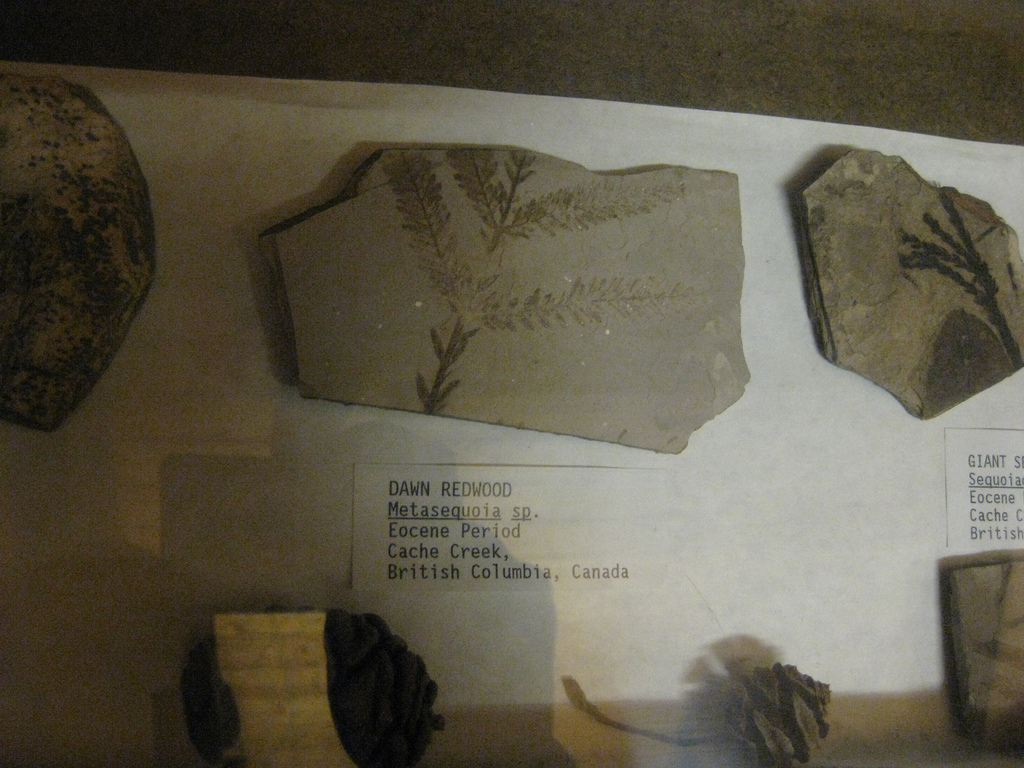

Imagine groves of such exotic trees as Dawn redwood, Gingko and Cunninghamia growing natively over a vast swathe of Western Canada and down into Washington and Oregon. Their leaves, seeds and flowers are preserved in exquisite detail in the fossil deposits of various localities from Cache Creek to Kitsilano. Some of these trees still survive, albeit in much diminished ranges, in parts of China and the southeastern United States, but a long-term cooling trend extirpated them from our own forests long ago.

Yet if global warming is threatening to bring back Eocene temperatures, why not reintroduce the Eocene forest? Many of our native trees are already suffering under the newer, hotter conditions, as is evidenced by the plague of pine beetles ravaging the forests of the Interior in response to milder winters. We can only hope that the native trees will survive by retreating northward, but the pace of warming is predicted to be rapid so it will be hard for natural plant migration to keep up.

Over the past dozen or so years, I have been introducing into my yard some of the tree species that once comprised British Columbia’s Eocene forests and I’ve been tracking their progress. Metasequoias in particular have done spectacularly well and a couple of my ten year-old specimens have reached 8 metres in height. These are amazing trees, deciduous conifers long thought to have been extinct, that caused a sensation when they were found surviving in a remote part of China, back in 1944. Their fossil remains are distributed all over the Northern hemisphere, from mid latitudes right up to the High Arctic, where their deciduous needles might have conferred them an advantage during the long, dark winters. Other Eocene trees I have successfully grown include Tetracentron, Scadiopitys, Cunninghamia, Podocarpus, Sequoia and Trachycarpus palms, all of which have flourished without winter protection, despite frosts as low as minus 15C and frequent deep snow. Members of the Juglans family (hickory and walnut) have also adapted well to my locality and I am steadily introducing other Eocene species to see how well they do.

Last year, I embarked on a collaboration with the botanist Rupert Sheldrake to scale up my initial trials to a landscape level. I initiated the planting of entire groves of Metasequoia, Juglans, Gingko and Coast Redwood, arranging them in clines, or habitat gradients on Rupert’s property – a 60 acre clear cut on the east side of Cortes Island. Though the winter of 2008 and the beginning of 2009 have been exceptionally dry, a good portion of the plantings have so far survived without supplemental watering. The Juglans and Sequoia in particular have taken well, on what for the most part is a very exposed, site, heavily disturbed by industrial logging. Work on the “Climate Change Forest” is ongoing and our hope is that the successes and failures we have in establishing formerly native tree species will yield useful information on the future of forests under conditions of global warming. Perhaps some of the trees might have a kind of genetic memory and will once again flourish here as they did so many aeons ago. If so, our reintroduction of these Eocene survivors might prove part of a larger strategy to manage the climate cataclysm we have only just begun to experience.

I did a paper on Metasequoia back in the day and remembered an earlier reference to living trees. I finally found it.

“In 1941, T. Kan, of the National Central University, [Nanjing], found a peculiar deciduous tree, at the village of [Modaoqi], south-east of [Wanxian], in [Sichuan], where it was named by the natives [shui-shan]. Owing to the season, no material was collected. It was not until 1944 that specimens were collected, at the same locality, by T. Wang of the Central Bureau of Forest Research, [Nanjing]. Wang thought his specimens belonged to the genus Glyptostrobus, but in 1945 they were examined by C. H. Wu (National Central University) who realized that they belonged to a conifer genus previously unknown in the living flora of China. This opinion was confirmed by Prof. Wan-Chun Cheng of the Central University and Dr. H. H. Hu, Director of the Fan Memorial Institute of Biology, Peiping”

“In 1946, Cheng sent out two expeditions under the leadership of his assistant, Dr. Hsueh, to collect more material and explore the region in search of more trees. Twenty-two additional trees were found and more adequate herbarium specimens were collected. Herbarium specimens were sent to the Arnold Arboretum (Harvard University) whose Director, Prof. E. D. Merrill, was able to obtain funds to finance another expedition to make a fuller investigation of the area and to collect more specimens and viable seeds. This expedition, partly organized by Dr. Hu and led by Dr. Hsueh, was sent out in September, 1946 and spent three months in the vicinity of the previously explored area and in the neighbouring Province of [Hubei]. The expedition found more than 100 large trees growing on slopes, along small streams and near rice paddies. …

“Seeds were received at the Arnold Arboretum early in January, 1948, and many had germinated before the end of the month. Mainly through the generosity of the Arnold Arboretum in sharing its seeds and seedlings, Metasequoia was soon propagated and distributed in many parts of North America and Europe as well as in eastern Asia”

Dallimore, William, Albert Bruce Jackson, and S.G. Harrison. 1967. A handbook of Coniferae and Ginkgoaceae, 4th ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press. xix, 729 p.

http://www.conifers.org/cu/me/index.htm

Thanks Neill. Took me for ages to find your comment in the sea of spam. The Metasequoia continue to prosper. I notice that BC ferries has planted them at the approach to Horseshoe Bay, giving the ferry waiting area a lovely Cretaceous feeling.

best,

O.

I am humbled by the work you are doing, Oliver. Thank you so much for this valuable contribution to our collective well being. How wonderful that you’re collaborating with Rupert Sheldrake! And thanks for continuing this blog. It is a rich & lyrical source of inspiration & information.