Those of you who’ve followed my blog for a while will know I am fascinated by the intellectual capabilities of slime moulds…

This is the time of year when the dark coniferous forests near my house get brightened up by their white and yellow blobs of sentient goo. Around here, they are mostly the common slime mould Fuligo septica – otherwise known as ‘Dog Vomit slime mould,’ a rather harsh name, in my opinion, for such an engaging life form.

Far from being vomit or mould, these slimy masses are actually swarms of social amoebae that have combined their protoplasm and nuclei into a single super-organism called a plasmodium.

Once formed, the plasmodium creeps along the forest floor until it reaches a tree stump or log, at which point it climbs to a high enough vantage point from where it releases its spores into the slightly more active air. These drift, land, and eventually germinate into another generation tiny amoebas that one day will seek each other out, meld together and then start their complicated social migration process again.

This is all very fascinating, but the reason slime moulds have been the subject of such intensive research is that their plasmodial masses show an uncanny ability to solve computational problems – which is all the more remarkable given that slime mould has neither brain or a nervous system and its constituent amoebae are about as rudimentary a life form as you can get. But when large numbers of these simple beings are networked into a swarm, the principle of emergence takes over and we begin to see a unified intelligence. The rules governing emergence are fairly simple – as long as each individual is aware of and able to exchange basic sensory information with its neighbours, stimuli can be transmitted throughout the network, which can then react as a sentient whole, flowing toward attractants or away from danger.

This simple yet powerful mechanism is behind the flocking of birds, the flow of traffic and the evolution of memes on the internet. It is a non-hierarchical, ‘ur’-intelligence, an organizing tendency imbued in the very vibrancy of matter itself.

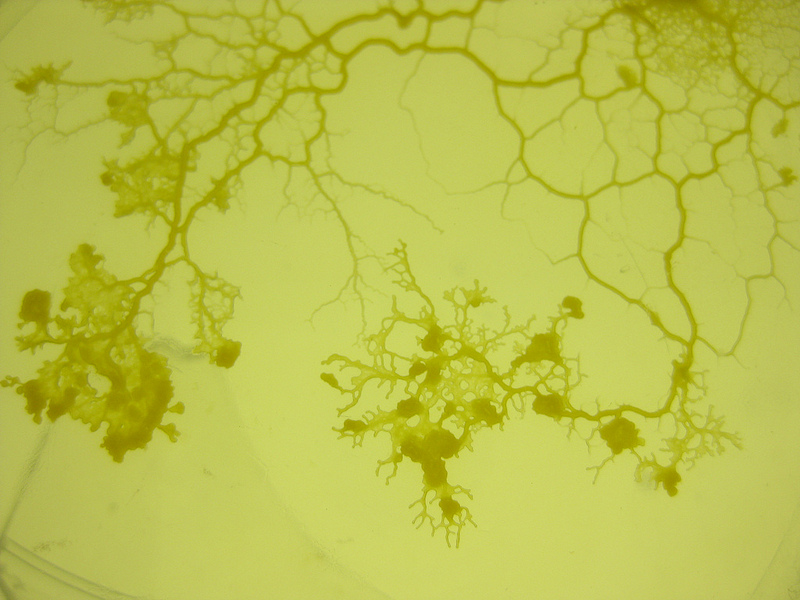

The lab rat of the slime mould world is the easy-to-raise species Physarum polycephalum and as such it has been the subject of much experimentation. Lured by oatmeal flakes, Physarum can outperform robots in solving mazes and it will figure out mathematically complex problems such as how to most efficiently connect an arrangement of arbitrary points, making it astonishingly good at designing highway networks and other mesh-like systems. Though brainless, Physarum has a rudimentary spatial memory. It recognizes where it has already explored by sensing the slime trails it has left behind, allowing it to focus its foraging energy on covering new ground.

Inspired by my time hanging around with the bio-geeks at Brooklyn’s GENSPACE, I decided to put old Physarum to the test by giving it some problems I thought worthy of its impressive powers.

1) The IKEA vexation:

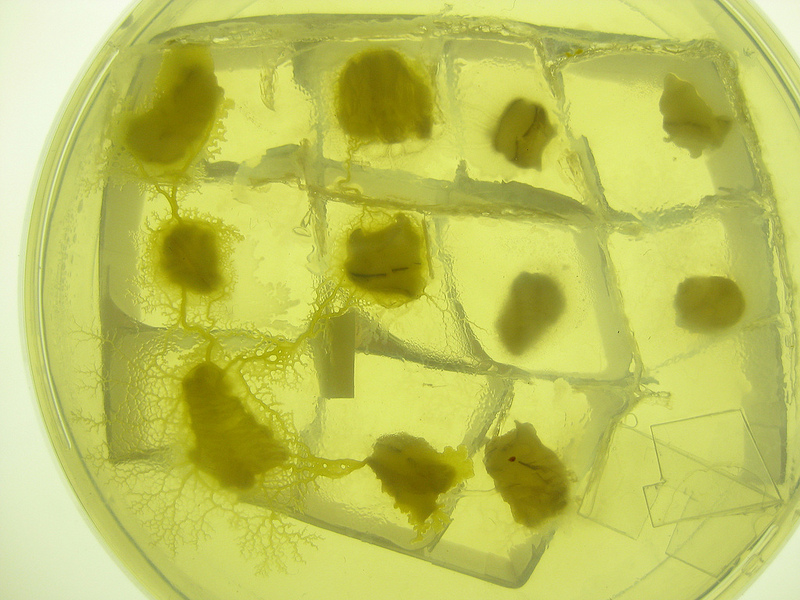

For years I have been irked by IKEA stores. What is the most efficient way to navigate through one of them? I find IKEA to be especially frustrating and always have had trouble finding my way toward the exit without being overcome by an anxious ‘trapped’ feeling. For me, IKEA is prime habitat for what it called the Gruen transfer – a deliberate architectural strategy aimed at disorienting people in shopping malls; an invocation of spatial confusion that makes us lose track of our original intentions and buy stuff we don’t need. I wondered if the slime mould could resist such distractions and efficiently find its way through an IKEA without getting sidetracked? To put this to the test, I built a tiny petri-dish sized model of the floor plan of the IKEA, modeled on the store in Richmond, British Columbia, which is more or less typical. Each department was baited with an oatmeal flake and I plunked a little bit of Physarum culture down near the store’s entrance to see what it could do.

2) The Future is out there:

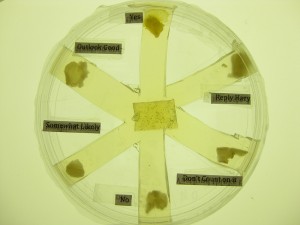

Decisions involving the future are hard for me to make, especially if there are a lot of equal seeming options. Throughout history, we’ve consulted soothsayers, fortune tellers and ouija boards in hopes we might get some guidance on how to choose between those many forks we encounter in life’s road. I’ve often despair and then make a seemingly random choice. If slime moulds are so good at solving problems in the here and now, how might they do in sussing out what hasn’t yet happened? Could they help me ‘Magic 8-Ball’ style make decisions on what to do next? Well, I was a little too clumsy to build a proper ‘8-Ball’, but I managed to make a reasonably convincing ‘6-Ball’ simulacrum, by cutting six (approximately identical) radial paths into the agar of a petri dish and having the slime mould choose which one it wanted to go down. I baited each ‘choice’ with a flake of oatmeal and labelled them: ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘outlook good,’ ‘reply hazy,’ ‘somewhat likely,’ and ‘don’t count on it!’ I’d ask the slime mould a (secret) question then wait a few hours to see what it decided.

Well those of you who have had scientific training are probably about to bust a blood vessel about now, but bear with me!

Perhaps predictably, the IKEA ‘maze’ problem was quickly solved by Physarum. It relentlessly streamed from one ‘department’ to the next in search of its oatmeal rewards and within a couple of days, it arrived at the exit hungry for more. This is a very basic slime mould-solvable problem. Physarum tends to behave in what is called a ‘ballistic’ manner; once they have sensed a stimulus they will try to flow toward it taking the most direct route possible.

Except when they don’t

Because unlike a non-sentient being, slime mould will often abort its migration toward an attractant, if it senses a rival has gotten there first. Sometimes though, competitors will merge into one happy super organism and share the the love and the bounty.

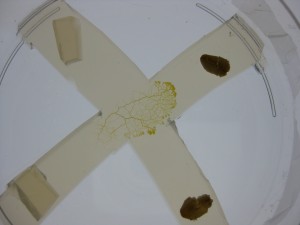

This makes for some interesting possibilities for ‘non-digital’ logic. Let’s say we place slime moulds, (let’s call them ‘A’ and ‘B’) in each of the two forks of a ‘Y’ shaped path and put an oatmeal flake in the remaining leg. If the slime moulds were to behave consistently that is to say ‘digitally’, you would have the basis for what is called an Exclusive ‘OR’ gate, a common component of computer logic. There has been some great research done on this by Andrew Adamatzky at the University of the West of England.

Given the slime moulds’ usual aversion to the presence of a rival, the one that gets to the bait first will dissuade the other. So in logic gate terms the presence of ‘A’ or ‘B’ (the inputs) will generate an output, i.e. either ‘A’ or ‘B’ gets to the oatmeal.

‘A’ and ‘B’ can’t both reach the oatmeal because the presence of one will (most of the time) repel the other, so the gate is considered ‘exclusive.’

But because slime moulds, though simple, are living things, with their own agency, they don’t always do what we expect. When the slime moulds ‘A’ and ‘B’ break convention and flow together to share the oatmeal, the logic gate becomes ‘non-exclusive,’ i.e input ‘A’ or ‘B’ or both can appear as outputs. Sometimes even that doesn’t happen and a slime mould gets distracted and decides to loiter around the perimeter of the petri dish, boycotting the experiment despite the presence of oatmeal. Who knows why? Are they following their bliss? Or are they just confused? To my mind, these ‘exceptions’ to the behaviour we deem ‘logical’ are the most interesting results. If we develop a new class of biological computers based on slime mould logic, the outputs generated might have a charming and useful variability. This could be used to more closely emulate the real world ‘twitchiness’ of such social phenomena as how people behave in the marketplace (they don’t always act rationally or in their self interest), or how they participate in riots or elections, which are also less than rational processes.

And as for predicting my future, the slime mould oracle was initially quite decisive. It answered my first (secret) question with a resounding ‘Yes,’ but then started creeping around to investigate other nearby possibilities. To me that seems like a perfectly reasonable approach.