The steady incursion of the coyote into North American cities is an outstanding example of the kind of hyper-ecologies I am interested in. Though it is native, the coyote evolved as an interstitial species, having to eke out a living in the ecological between the wolf and the fox, and so it always had to be adaptable. Vacant industrial lands and suburban cul-de-sacs have become as much home to the coyote as the arroyos and sage steppes of its traditional habitats, but they offer rich new food sources in the form of ubiquitous garbage and dim-witted house pets. Quick to learn and selectively omnivorous, the coyote thrives in the wreckage of wilderness, where its larger cousin the wolf has been largely extirpated.

Among the sidewalks and rhododendrons and stupendously overpriced little stucco houses of East Vancouver, I was charmed to come across one of these clever canids, making its rounds; methodically investigating the driveways and gaps between houses for a chance at some badly packed trash or a succulent, over-fed cat. I followed it for, a while and though it seemed well aware of my presence, it maintained just enough distance to continue with its nonchalant foraging, never once breaking its stride. Despite our fantasies of control over our built environments, there is no doubt in my mind who will ultimately inherit them. Whether tearing into our garbage or chewing on our bloated corpses, the coyote will surely outlast us. Whether we like it or not, the future is feral…

|

||||||

|

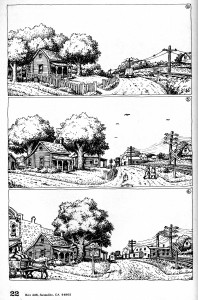

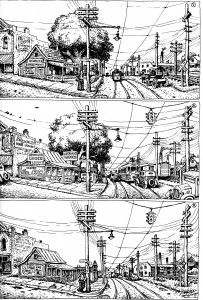

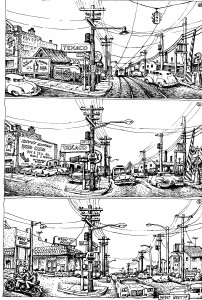

At the very end of March, I went back to Mississauga, my home town, city, conurbation (I don’t even know what to call it!) to visit my elderly parents. My dad was up for a heritage award for his work in a campaign to restore the steeple of the church, (Presbyterian), he and my mother have been attending for years. A charming little brick edifice dating back to the 1870’s, its steeple was smitten from the tower by lightning in 1920, and then hastily replaced with an ignominious asphalt shingled pyramid, which stayed there for the next 90 years. As a retirement project, Pop, who was, by the way, brought up a Swabian Lutheran, organized getting a replica of the original (wooden) spire made in lightning resistant steel and he and the other parishioners were thrilled to see it hoisted into place by a giant crane. The result, it has to be said, is quite handsome as the church sits atop a hill and has now regained its long lost stature as a landmark, with a much more commanding presence over the nearby houses and the vale of the Credit River, a visible link to the past in a context in which most such points of historical reference have been wiped out. ‘She’s been ruling Mississauga with an iron fist for 33 years,’ I heard someone say. ‘And everyone’s damn proud of her – Damn proud!’ Perhaps I caught a whiff of UBIK, or something, but as I sat there I was overcome by a strange feeling as if I’ve been asleep for a long time and had awoken, like Rip Van Winkle, into a distant future. It is 1968 and I’m a boy standing in a warm field of yellow goldenrod and mauve Virginia asters and into the shimmering distance sweeps a blonde expanse of pasture and corn stubble and here and there, a weathered grey barn or a small woodlot punctuated by the vermilion of sumac and swamp maple. Above it all, the crows caw and wheel and a contrail dissolves slowly into the great blue dome of the sky, reminding me that it is, after all the jet age. It was a dirt road that brought us here, my father and I, and we have come to shift the wire pens that contain the flock of unruly geese we are raising in a not-very-profitable after-work venture that dad had concocted to ‘help make ends meet,’ as he likes to say. The farm has been rented by a certain Mr. Baker, a taciturn workmate of his from the factory at which they spend their days supervising the machinery that spits out concrete blocks onto an assembly line and he is in the background right now quietly, as is his manner, tending a couple of horses that belong to his teenaged daughters. Robert Crumb’s version of North American History from Fall 1979’s Coevolution Quarterly |

||||||

|

Powered by WordPress · Atahualpa Theme by BytesForAll |

||||||