I’m in New York again and have been here for a while. Right now, it’s about 3 pm, outside Washington Square Park, on the first day of 2012. A man wearing an expensive overcoat is projectile vomiting against a tree – a linden, I believe it is. An eager pug strains at its leash to lap up the mess, but the firm hand of his mistress snaps him back at the last instant.

New Year’s eve—the East Village was full of young women in spangly short skirts and tottery high heels, throwing up in the street and crying, while their boyfriends bellowed primal indignation at the indifferent, night air. Overhead, police helicopters rumbled and sirens caterwauled from all directions as Zuccotti Park, one of the city’s parsimoniously conceived ‘privately-owned public spaces’ got temporarily re-occupied by the anti-Wall Street protesters, before the riot-garbed might of New York’s finest wrested it back from the dangerous band of raw food enthusiasts and bicycle couriers (who posed such a clear and present threat to the security of this, the most powerful nation on earth), while each round of pepper spray and arm twist got live streamed into the ether by a hovering coterie of electro-pundits. All in all, it was a hell of an evening.

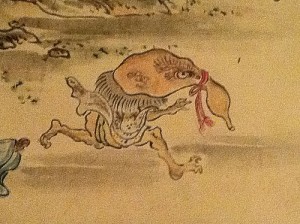

It’s been a long time since I’ve seen so much purging. It is said that Tibetan soothsayers and the Oracle of Delphi vomited after making their prognostications. The future made them sick, but then the past isn’t always so great either, and in 2011, the world seemed thoroughly to have gotten sick of itself. Though Occupy and the Arab Spring reminded us that entrenched, globalized systems of neo-Liberal economics and authoritarian government have (to quote Zizek) “lost their automatic legitimacy,” the outlook for the global environment has never, in the history of humanity, been so grim.

While some still pine for the evaporating American Dream, the opportunity to avert catastrophic climate change and forestall the extinction of countless fascinating species is slipping through our fingers like so many Styrofoam peanuts. Of course, at least subconsciously, we can all sense it, and to cope with the ubiquitous sensation of doom we sedate ourselves with apocalyptic pop culture, never more prevalent, as a casual perusal of Wikipedia’s listing on apocalyptically-themed video games will attest. These digital dystopias of burned out cities and smouldering, post-ecological terrains have infiltrated our optical-subconscious to the degree that we now feel increasingly at home in them, making the vestiges of the real, biological environment seem aberrant and atavistic.

You’re wondering now,

What to do,

Now you know,

This is the end.

Andy and Joey: Original Ska Version, 1964

Not to be outdone, I recently arranged my own ‘Apocalypse-athon’ watching Lars von Trier’s Melancholia and Jeff Nichols’ Take Shelter, more or less back-to-back, and I have to say the experience left me feeling strangely numb, as if someone had thoughtfully smeared Novocain on the insides of my wrists before handing me the X-acto knife to do myself in.

Let’s face it — contemplating the end of the world can give us a kind of frisson by stoking our anthropocentric egos, because after all, on some level, we would like to think the world will end with us. But that’s not likely to happen. There are plenty of tougher organisms out there who’d be happy to feed on our heaped, irradiated carcasses, while they watch us fade into geological history. Perhaps the rats and kudzu vines or whatever else moves in to take our place as the planet’s most visible organisms can work out a more sustainable contract with the planet than we did. One can only hope.

Barring all-out nuclear war or withering pandemic, our world, as we know it, will continue to diminish in increments —a forest here, a coral reef there, a watershed in some distant part of the world or maybe a bit closer to home.

A sad and perhaps typical small example of such ‘death by a thousand cuts,’ is taking place right now on Cortes Island— a mostly overlooked, densely forested blob of rock, off the inner coast of Vancouver Island, where I live part time. With its abundance of wild mushrooms, smurf-like New Age seniors and flaxen-haired hippie children, it can sometimes feel like living in the label of a Celestial Seasonings tea box, yet through good fortune and its reputation for a fierce culture of environmentalism, Cortes has been left with a few tracts of magnificent, old Coastal Douglas fir forest, a type of habitat largely extirpated from its former eastern Vancouver Island range. This enchanting ecosystem, where individual trees can tower to 200 feet, is the habitat of mountain lions, a unique maritime race of timber wolf, the endangered Queen Charlotte goshawk, rare bats, and an amazing diversity of fungi —some of them, such as the medicinally potent Agarikon, exclusively dependent on this age class and variety of tree.

Yet precisely because of their rarity, these large old trees are now valuable on the international timber market and have of late been under the acquisitive scrutiny of the corporate Eye of Sauron.

In a twist of globalized connectivity, Brookfield Asset Management, the company behind the eviction of the Occupy Wall Street protestors from New York’s Zuccotti Park (which they own) recently bought up much of Cortes Island’s standing inventory of mature forest, which also contains most of island’s remaining old growth, particularly of Douglas fir.

Brookfield markets its Island Timberlands division to potential investors as:

One of the best sources of large Douglas fir, hemlock and cedar in North America for a broad customer base primarily located in Asia and North America…

Brookfield’s business model is perfectly clear: buy up the last commercially available pockets of ancient forest and liquidate them for maximum profit. This is eco-cide, pure and simple, but there may be little the good people of Cortes can do about it, save for physically blockading the logging equipment as it arrives in, to delay what perhaps is inevitable. In British Columbia’s privately owned forest lands, property rights trump all other environmental and social concerns, a status quo the forest industry lobbied hard to achieve, with substantial contributions to the governing Liberal party, who rewarded them by gutting regulation and oversight in a revised Private Managed Forest Land Act.

As outlined in their prospectus:

Brookfield focuses on investments in the region with a strongly embedded concept of private property rights generally supported by effective legal and land title systems.

By effective, they of course mean ‘industry friendly’ and the legal system in British Columbia is definitely that. Yet 2011 was the year people the world over stopped seeing the property rights of corporations as ‘self-evident’ and ‘automatically legitimate,’ when such rights override the well-being of communities and the environment. That is what the OWS movement was all about. What Cortes needs right now, is a massive ‘Forest Occupy’ response from those committed to maintaining the integrity of the vanishing ancient Coastal Douglas fir ecosystem in the face of a determined corporate assault. But will the islanders be able to muster the hundreds of occupiers it will take to pull this off? We’ll have to wait and see. Island Timberland plans to start its operations later this January.

But what if Brookfield/IT prevails and logs off the venerable trees from its Cortes lands? To be sure, investors in its Timberlands private funds will get a little richer as the ships full of ancient logs ply their way across the Pacific and get fed into the maw of the Chinese construction industry. There is a painful symmetry in the fact that the profit squeezed from liquidating some of the last 1% of the original, ancient Douglas firs left on British Columbia’s coast will further line the pockets of society’s wealthiest 1%.

They probably won’t even notice. Environmentalists and bird-watchers will likely get a little more depressed as the sitings of Queen Charlotte goshawks and rare bats decline with the elimination of their prime breeding grounds, but even these people will start to focus on other things as the giant stumps sink slowly into the shrubby verdure of second growth. The timber company might even replant the ravaged land with industrially reared seedlings, each one secure under its own deer-resistant plastic cap. Gradually, what Jared Diamond calls ‘landscape amnesia’ will settle in and the degraded, industrially abused landscape will simply become ‘the new normal.’ And that to my mind is the greatest tragedy of all. We’ll lose something once basic to the human experience— the sense that a truly wild and ancient landscape can exist solely on its own terms, for everyone to appreciate, and not be sold out for the financial betterment of a wealthy few.

This is the way the world ends,

This is the way the world ends,

This is the way the world ends,

Not with a bang but a whimper…

T.S. Eliot – The Hollow Men