glass case at entrance to Darwin show

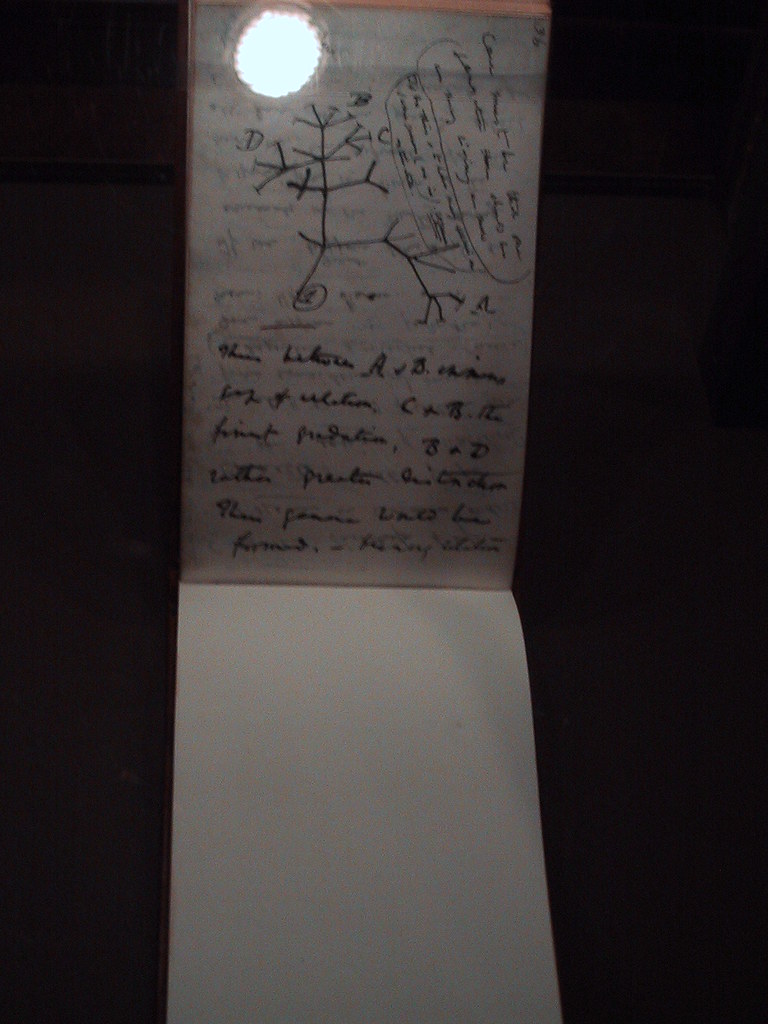

page from Darwin’s notebook

This nightmare has nothing to do with Hubert Sauper’s brilliant documentary of the same name.

No.

‘Nightmare’ was what came to mind as I was being herded though the dark cattle chute that constitutes the American Museum of Natural History’s new blockbuster Charles Darwin exhibition.

Ruth joked that with the show’s stinging $21 admission fee, it’s no wonder America’s poor don’t believe in evolution. It’s cheaper to go to church.

Such is the power of the religious right in America that, according to a recent New Yorker article, the Darwin exhibition failed to garner a single corporate sponsor.

Yet downstairs in the same museum is the glitzy, permanent Hall of Biodiversity, funded by biotech behemoth Monsanto and open since 1998. One its most noticeable features is the giant Spectrum of Life, a schematic display that shows the diversifying of species from a common ancestor—a central principle in Darwin’s evolution theory. Nuance seems to be everything though—Monsanto can use the word ‘biodiversity’ because it reflects positively on its biotech brand but ‘Darwin,’ eighty years after the Scopes Monkey Trial, is still dirty a dirty word in America. Given this monumental handicap, it is a miracle the Darwin show happened at all. And for that at least I am grateful.

Full of good intentions, we found ourselves queueing outside the exhibit, waiting for the time slot in which we would be allowed to enter. Immediately, I realized that this was going to be one of those shows in which Taylorism triumphed over edification. It seems that almost every so-called ‘special exhibition’ put on by major museums and galleries these days is designed as an exercise in industrial operations management; the primary objective being to quickly process the maximum number of bodies, before ejecting them summarily into the gift shop waiting at the end of the assembly line.

‘Darwin’ proved to be no exception. It’s dark, chute-like architecture brought to mind something slaughterhouse diva Temple Grandin might design.

At our prescribed entry time, we were literally herded through a narrow anteroom toward the first of the glass cases. My claustrophobia kicked in and I imagined that instead of a gift shop, there might be a killing floor waiting for us at the other end, manned perhaps by Christian fundamentalists with bolt guns.

Trying to calm myself, I slipped my trusty little Canon Elph out of my pocket to try and document the mayhem.

Immediately, I was set upon by a burly guard with a shiny shaved head.

“No Pictures !!!,” he barked

OK, OK, I said . . .

We continued to be propelled forward by the human tide until thankfully the hall got a little wider. As we were milling around trying to catch a glimpse of an assemblage of stuffed finches and a disconsolate looking iguana in a terrarium, I heard a high school girl complaining to her teacher that she just ‘didn’t get it!’

The guards continued to wade pugnaciously through the crowd, swooping in on anyone who dared pull out a camera or even a cell phone. It was as if they had been warned that Darwin’s theory was so dangerous, it couldn’t under any circumstances be allowed to leak out beyond the building. Which was surprising, because there really weren’t any artifacts on display that could in any way be construed as controversial. It was all very low key, almost to a fault.

I dislike photography bans in public institutions at the best of times, so I was determined to beat this one, particularly since Darwin’s ideas are so important to our modern intellectual commons. As long as I wasn’t using a flash, what harm could it do?

But it became a moot point. The displays were so woefully under-lit that I abandoned my plan, snagging only one more grainy image. It was however, what I had come to see— a page from one of Darwin’s original notebooks; a tree-like cladogram, in which a number of species evolve from a common ancestor, diversifying in a pattern of adaptive radiation. This simple sketch might well depict the exact moment of Darwin’s great epiphany. He had scrawled the words “I think” above and to the left of the little tree, in a heartbreaking gesture of tentativeness. Oddly, this caption is hidden in the photo I took, obscured by a stray reflection from an overhead light. No matter though, seeing it for real was worth the price of admission.

A half hour after I gave up on any further photography, a female guard confronted me, demanding to know if I had taken any pictures.

No, I lied, reflexively .

What else could I do?

I was after all in a nation that had declared unambiguous war on journalists. Perhaps, while I wasn’t looking, a corporation had bought the rights to the theory of evolution and I was about to get sued for infringement of copyright. She looked at me askance before lumbering away. I knew I would continue to be watched.

Things were a little more genteel in Darwin’s day.

I was touched by the exchange of letters between Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, the theory of evolution’s lesser known co-creator, whose life as an itinerant butterfly collector seemed to consist of an endless morass of tropical fevers and shipwrecks. Both men went to great lengths to give each other credit for their ideas, so much so that in one letter Wallace expresses his “pain and regret” that Darwin withheld his own paper on evolution, so that Wallace could be given the opportunity to co-present his paper with him in front of the Royal Society.

Darwin later wrote to Wallace:

I hope it is a satisfaction to you to reflect—and very few things in my life have been more satisfactory to me— that we have never felt any jealousy toward each other . . .

Interestingly, Darwin had another prodigiously intellectual admirer, by the name of Karl Marx. The latter was so taken with Darwin that he wanted to dedicate the second part of Das Kapital to him; an honour that Darwin alas declined.

Not surprisingly, the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species was hugely controversial, sending the religious establishment of the day into a state of apoplexy. What is harder to understand is why, today, given the unassailable mountain of evidence, is the theory of evolution still controversial? While the Darwin exhibition soft-pedalled the case against evolution’s nay sayers, evolution remains as clearly observable a phenomenon as gravity. It may be difficult to agree on what causes gravity, but most people acknowledge that it exists. Not so with evolution.

The spectacular recent find in the Canadian Arctic of the fossil Tiktaalik is a case in point. This creature is the perfect snapshot of a transition from fish into land animals. If this isn’t an example of evolution served up on a silver platter, I don’t know what is.

Tiktaalik roseae

One need only look to the annual mutations of the flu virus to get an object lesson in evolutionary biology. The practise of modern epidemiology just wouldn’t be possible without evolution being understood, not just as a theory, but as a demonstrable, empirical truth. Viruses mutate and evolve and vaccines need to be constantly adjusted accordingly.

Matthew Chapman, Darwin’s great grandson, wrote a hilarious, yet compassionate article in Harper’s detailing his experiences of the Pennsylvania trial in which a group of parents sued the Dover Area School District to get “intelligent design” taken off the local science curriculum. The proponents of ID promote what is essentially a quasi-scientific re-packaging of Christian fundamentalism, as a theory every bit as scientifically valid as evolution. The ID movement has infiltrated numerous American school boards by framing its overtly religious philosophy as an issue of free speech, in which the teaching of evolution needs to be somehow ‘balanced’ by the teaching of intelligent design. It is the slippery slope to a new kind of Lysenkoism, the triumph of ideology over empirical fact, a trend which has become all too common in contemporary America.

Understandably though, given the technological limitations of his time, Darwin didn’t get it completely right. Recent studies have shown that evolution can be sped up considerably, beyond what is afforded by the glacially slow mechanism of random mutation acted upon by natural selection. Apparently, organisms of different species can actually swap DNA, creating what a recent article in the New Scientist calls interspecies ‘gene flow.’ This speeds up the evolution of new species by rapidly increasing the complexity and variety of available genetic traits. Of course this could be viewed as a kind of ‘intelligence’ but it is intelligent in a beautiful, intrinsic kind of way, akin to the phenomenon of emergence, in which complex functionality and behaviours can arise from the interconnection of simple elements.

A belief in evolution does not of course negate a belief in God. As far back as 1908, American nature writer John Burroughs argued that evolution should not be viewed as an insult to the dignity of humanity but as evidence of the divine in nature. One of his essays has been excerpted in May’s Atlantic Monthly. This passage particularly struck me:

It jars our sensibilities and disturbs our preconceived notions to be told that the spiritual has its roots in the carnal and is as truly its product as the flower is the product of the roots and the stalk of the plant. The conception does not cheapen or degrade the spiritual, it elevates the carnal, the material. To regard the soul and body as one, or to ascribe to consciousness a physiological origin, is not detracting from its divinity, it is rather conferring divinity upon the body. One thing is inevitably linked with the other, the higher forms with the lower forms, the butterfly with the grub, the flower with the root, the food we eat with the thought we think, the poem we right or the picture we paint, with the process of digestion and nutrition.

I wish someone had taught me that in school.

Perhaps the most endearing part of the AMNH’s Darwin show is the provision of a tortoise cam , which streams the ponderous peregrinations of the exhibit’s two resident Galapagos tortoises out onto the internet, for free. For all of the impact they had on Darwin, tortoises are sadly an evolutionary dead end. Unlike the dinosaurs, they never really evolved into anything else, remaining more or less unchanged since the Triassic. Maybe it’s because they are already perfect. Next spring I will celebrate my 40th anniversary with Marmaduke, my male box turtle; not a tortoise really but a kind of terrestrial turtle native to the eastern United States. I bought him at a pet store with my allowance money in the spring of 1967, when I was just eight years old. He has been my stalwart companion ever since, enduring life in motel rooms, being on more than one occasion mailed across the continent and being slept on for a week by mistake when he crawled underneath my futon. These days, he alternates between basking in the pools of sunlight on my office floor and taking long, multi-day naps in the shadows beneath the bookshelf. When I look into the ancient twinkle of his wise reptilian eyes, I see divinity.

Marmaduke: a box turtle in his late forties