|

|

-

dead after four centuries

I’ve never seen a tree before. It’s pretty!

It’s dead…

Blade Runner 2049

Death is a complicated business and how one might feel about a particular death has a lot to do with how understandable it was, how inevitable. The loss of a loved one, near and dear, opens up a hole and the memories that flood in to fill it, though they might bring comfort, never completely make up for the extinguishment, the permanent elimination of an actual physical being from our lives. It is the finality of death that makes it so daunting. Most of us realize this (of course!) but we wish it weren’t true. We mitigate our grief by imagining our dear departed being ‘in a better place’ or ‘resting in peace’ or otherwise liberated from mortal suffering as if after death some remnant of the self might still remain that is able to experience relief. Who knows? Maybe dead is just dead?

Within the span of a year, I lost both my parents. ‘Lost’ is a strange way to put it – I know where they are – their cremains scattered under some bushes against the red brick wall of an old church beside a highway in suburban Toronto. The ground there shakes every time a big truck rolls by, which is pretty often due to the heavy traffic. Mom and Dad chose this spot many years ago when their deaths still seemed like a far-off possibility. Though they were both in their eighties by the time they passed on, (an average lifespan in Canada which still retains the tattered remnants of a public healthcare system, the way they each died came as a surprise. I don’t know what I was expecting really. Perhaps I had just put the inevitability of them dying out of my mind until the medical emergencies started to pile on, one after the other and their mortality became impossible to ignore. Yet the end of life is an issue we all have to face, sooner or later, ready or not.

As to why my parents wanted to be interred next to that particular church–it was because they’d developed a deep affinity for both the building and the community that congregated in it. That it was a Presbyterian church and they had always identified as German Lutherans didn’t seem to be a problem for them. At the top of a hill overlooking a sweeping river valley, the little church serves as a landmark in the neighbourhood where they had established deep roots. Before his mind started unravelling, Dad spent years as a church elder, overseeing the renovation of the steeple and visiting the sick. The memory garden where I scattered his and Mom’s ashes was installed by my brother, his first major commission after landscaping school. Our family home was just down the road in an old red brick house of similar vintage to the church, since we moved there in 1969. My parents lived there until it seemed prudent for them to downsize to a nearby apartment when Dad started his long decline.

not cornfields anymore! Mom and Dad arrived in Canada in the late 1950s as impecunious immigrants from a war-ravaged Germany and I was born shortly thereafter. At that time, Dad did night shifts in a styrene factory as well as serving as the superintendent for the walkup apartment building where we lived. Mom toile away as a supermarket cashier. With the hard work and determination of the immigrant working class, Mom and Dad eventually rode the surging tide of Canada’s postwar economy from their blue-collar beginnings into the ranks of the lower middle class. The high point was when Dad got promoted from the factory floor to salesman, a job that came with a company car. When that happened, Mom celebratoriously ditched her unionized cashier job for a less remunerative one as a bank teller which she thought conveyed a higher social status because she could ‘wear nice clothes’ and not be spending her days stuffing bleeding chickens into paper bags at the cash register. Mom and Dad weren’t the bourgeoisie exactly but they genuinely felt they had made it in this new land of opportunity. We children came along in tidy five-year intervals, first me, just squeezing into the tail of the 1950s, my sister following in 1964, and my brother in ’69. Dutiful and committed, my parents continued to build their immigrant dream, rarely complaining through life’s many trials and reminding us children on regular occasions life was ‘so much better now than it was during the war,’ which of course it must have been – not that we were in any position to judge. They maintained decades-long friendships, mostly within the German diaspora and gave their time generously to various community causes. After all those years of living, loving and helping others, their lives simply ran out, one after the other, within the span of just over a year. We who were bereaved are left with our memories of course, but in the end, all that was left of Mom and Dad was sticky grey ash, not even enough to fill the small wooden box which I carried out to the churchyard to sprinkle onto the shrubs.

So how did it all go down, their deaths? And did they make any sense?

On the face of it, the way each of my parents’ lives ended did make some basic sense though it would be nice if they had been able to live a bit longer. Their lives each spooled out as all of ours will–my mother’s abruptly, and my father’s more slowly. The details will vary of course, but the end is assured. The luckiest of us might get to die peacefully in our beds deep in old age but for the rest, our demise might just as easily be precipitous. Life expectancy in OECD countries like Canada is currently averaging at 80.3 years. In the US, where I now live, the expected life span is actually dropping but still averages out at 78.7. Mom and Dad both made it past the eighty-year mark and thus died within an unremarkable window of longevity.

Before his Alzheimer’s, Dad had struggled with two major bouts of cancer, a legacy of his time working with toxic chemicals – first in a styrene plant, around the time that I was born, then subsequently in a factory producing Fiberglass fronted concrete blocks, conceived to speed up the construction of fast-food restaurants that were popping up like mushrooms all over Toronto’s rapidly-developing bedroom communities like the one in which we lived. My earliest memories of Dad are his smell. I remember the odour of burnt styrofoam emanating from the pores of his skin when he brought his face close to mine after returning home from the plant. The car upholstery smelled the same way, having absorbed his plastic-scented perspiration. It was just the way Dad smelled and the presence of his personal polystyrene cloud served to comfort me and made me feel safe.

Mercifully his cancer didn’t kick until he was nearing retirement, albeit a retirement that was involuntary, due to a corporate merger that subsumed the company he had given so much of his life to, from his years in the plant to his ascendance to the sales force. Neoliberalism had hit its stride after NAFTA was signed and the good jobs in Southern Ontario’s manufacturing heartland began predictably evaporating as companies took advantage of the opportunities to shift production to countries where labour was cheap. All over the region, legions of loyal workers were cut adrift. For many like my father, the immigrant dream was beginning to unravel.

I can’t help thinking that the psychological stresses of this precarious time strained his health, but at least Dad saw see his children grow up before getting hit by the big ‘C’. When cancer came, he took it surprisingly in stride. The first round was a near-fatal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, cancer that typically affects workers exposed to the type of chemicals that are used in plastic manufacturing. Intense chemotherapy was needed to bring it under control and even then, it was a long time before his remission could be assured. The irony that it took exposure to toxic chemicals to cause cancer and more toxic chemicals to take it away was not lost on Dad. By the time he was in remission, Dad was wrung out and never again regained his once-prodigious vitality. His personality changed too and he became much more reflective and less prone to the piques of anger he had been predisposed to. To those who loved him, it was a change for the better and I was moved to hear him talk about the long hours he spent volunteering at the cancer ward where he himself had been treated, reassuring anxious new patients splayed out on the leatherette recliners with chemo transfusions coursing through their blood vessels. I have no doubt his quirky humor and general bonhomie kept more than a few cancer patients from sinking deeper into their despair and I got the sense he was suddenly determined to give something back to the world after himself being granted a new chance at life.

But it wasn’t long before another cancer swooped down on him like a malevolent front – bowel cancer this time. The good news was it had been detected early and his doctors were guardedly optimistic he might recover. The surgery went without complications but disaster struck during what was supposed to be the postop. Dad was nearly killed when the hospital staff ill-advisedly rushed him into eating solid food. Not wanting to disappoint but nauseous and still in pain, Dad choked and inhaled his own vomit, the violent coughing that ensued bursting the sutures in his intestines. Emergency surgery followed but he was now also struck with aspiration pneumonia triggered by the food sucked into his lungs. He went from a cheerful convalescence to death’s door in the matter of a day and was unconscious in the ER amid beeping machines. Called to his bedside, I expected the worst. Flying in from British Columbia, I made sure to pack a dark suit to wear at his funeral, which everyone agreed was imminent. Amazingly, by the time I had arrived, the tide had turned and his doctors were allowing he might make a slow and somewhat complicated recovery. Mom, ever the tireless caregiver, nursed him through the multi-month convalescence that followed

Dad slowly recovered but his weakness was intractable and he seemed mentally dissociated. Though things at first seemed hopeful, in a cruel twist of fate, his cognitive state started showing signs of worrying impairment. At first, it seemed like post-surgery depression but then it became clear something more serious was wrong. The initial bouts of confusion he suffered after moving into the new apartment progressed into bouts of catatonia and continued exhaustion that worsened by the month. Dad lost his ability to speak, outside of a few unintelligible mutterings and refused to be roused from his bed. Mom was angry at him, accusing him of ‘just not making an effort’ but he continued to stare blankly into space. Alzheimer’s was confirmed and Mom’s toil now became never-ending. She had to cajole him into eating, and if he did put food into his mouth, make sure he remembered to chew. A cautious driver, she ferried him to countless medical appointments throughout the vast suburbs and as he was now incontinent, launder endless loads of his soiled undergarments and bedding. It wasn’t long before Mom slipped into a serious depression and she confided in me during her telephone calls to me in New York, where I was now living, that she was losing hope. Mom’s Sisyphean labours ended only when Dad happened to fall out of his bed one day, breaking his hip. As he recovered in hospital, the medical team finally realized the severity of his mental impairment and fast-tracked him into a dementia care facility. It had been obvious to all of us that my increasingly frail mother could no longer cope, and sad but relieved, she began to realize that with Dad taken care of, she could begin to focus on her own health issues.

Yet paradoxically Mom died before Dad did. It was sepsis that killed her after routine hip surgery; surgery I’d been hectoring her to have now that she had the time to begin looking after herself. Mom had been suffering from hip pain for years, affecting her sleep and forcing her to rely on a cane, which she hated. Her GP told her she was an ideal candidate as she was relatively fit for her age.

‘Go get your hip fixed..’ I implored her. ‘It’ll improve your life and you can ditch that cane.’

I soon came to regret those words and my naive faith in the infallibility of modern medicine.

Mom’s was a painful passing. She’d been recovering well after surgery and my brother had prudently booked her in for a temporary stay at a care home so she could recuperate with regular meals and monitoring. After Dad had been institutionalized, Mom was increasingly forgetful when it came to taking care of herself. When the time came for her my brother to take her home, she seemed lethargic yet still eager to leave. She was having trouble dressing and on the way down to the car, she collapsed in the elevator. By the time she was in the hospital emergency room, it seemed at first as if it was nothing more than a touch of the flu but soon her condition became much more serious. Mom’s vital signs were in freefall and the doctors scrambled to identify a virulent infection raging through her body. Her tissues started to swell and she became wracked in unimaginable pain. Mom soon lost consciousness and was dead within a couple of days. I sat vigil by her bedside as the voracious bacillus ate its way through her organs, while outside the window of the newly-built suburban hospital, sprawling over the featureless vastness of what used to be farmers’ fields, the gold and vermilion foliage of an Ontario autumn scintillated under the gas flame blue sky. Mom drew her last breath and I flew back to NYC to return to my work and await her upcoming funeral. A couple of weeks later I was back, standing in the churchyard, clutching a small wooden box that contained all that was left of her –a pile of grey ashes and some flecks of white bone.

As the first-born, the pastor instructed me I was to be the first to scatter her ashes. It was, to be honest, a little awkward, as there was a stiff breeze blowing in from the highway that caught them up, swirling them around me as I struggled to dispense the box with at least a modicum of dignity. My jacket sleeve, wrist and hand were soon covered in a clingy grey film of Mom’s mortal remains as the line of mourners formed to shake my hand. My melancholy flipped quickly into anxiety as it seemed crass to concern myself with tidiness at such a solemn time, to be wiping Mom off –the last vestiges of my mother’s corporeal existence– onto a scrunched up wad of toilet paper I had been kneading in the pocket of my jacket, while everyone else was watching, scrutinizing even, my performance with such focussed kindness and compassion. There was really no recourse, so for the sake of decorum, I turned away for a second and wiped my hand, just my sister was taking her turn doling out the cremains, my brother standing by her with the tears welling up in his eyes. It was all over in a few minutes, the last traces of Mom melding in with the topsoil and mulch (well more or less anyway–there were a few alarmingly un-melded spots I was hoping the groundskeeper would see to– the highway traffic unabated in its thrumming and the assembled party filing into an adjacent reception room for a buffet of coffee and sandwiches and a spread of homemade baked goods that would have truly lifted Mom’s carbohydrate-admiring heart, had she been present on this earthly plane to partake of it. Dad, mute in his dementia, sat transfixed in his wheelchair. He hadn’t uttered a word for the past several months and Mom had been taking it quite personally, despite the unambiguousness of his diagnosis, still stuck on the idea that somehow he was shutting her out when she made such an effort to visit him on his ward. During the service, Dad seemed to show some slight flicker of recognition when confronted with familiar faces from his congregation and he gazed searchingly into the eyes of those greeting him, though there was no indication he comprehended the tragic reason for this occasion. Perhaps it was better that way. Dad had been a mercurially emotional man. Though his relationship with Mom had been complicated in terms of its power dynamic, losing her after over 65 years of marriage might well have unmoored him beyond recovery had he still been in his right mind. But he wasn’t in his right mind, and that was that, and though my siblings and I hoped he might still have some sense of how much we all loved him, what remained of his subjectivity was now completely opaque, stuck in a labyrinth of blind neurological channels, mired in amyloid plaque.

The death of someone we love is so emotionally overwhelming, one is bound to perceive the moments around its occurrence differently from more quotidian happenings. It is the details that stand out, the small things, and the sensation of Mom’s ashes coating my sleeve, wrist and hand will always be with me. Life, as we know it at any given time, exists in a swarm of such moments, a cloud perhaps, and yet some of these fleeting perceptions manage to lose their ephemerality and become fixed in our memories, a permanent reminder of who we are, who we have been, the transitions through which we have passed, though they might only have lasted an instant, like the dust of Mom’s ashes swirling around me in the stiff breeze beside the highway, the way it felt in my hand, the sound of traffic humming as it passed.

The following spring, in a nondescript care home unobtrusively situated in the vast planar landscape of strip malls and low rise office buildings that characterizes Toronto’s amorphous edge, Dad’s decline suddenly accelerated. In keeping with the advance directives he had long ago prepared while still of sound mind, there was to be no medical intervention once he started refusing food and could no longer be roused from bed. He had, as I was told, spent previous weeks withdrawing even further from interactions with his caregivers, though he seemed beguiled occasionally by some atmospheric thing like the flash of windshields from the traffic outside his window bouncing off the ceiling of his room. He showed no signs of unhappiness or agitation, but rather what had remained of his neural functions were now simply shutting down, which to his nurses signalled his life was drawing to a close. We gathered by his bedside to wait for the inevitable; me, my brother and sister and their spouses, while various friends and former neighbours came and went, paying their respects, sharing memories, making small talk with us and drinking coffee. Dad had been a gregarious man and though now unconscious, we all shared the thought he might have been comforted by all of us being there. He wouldn’t have wanted to die alone. The weather outside was pleasant and we had just returned from stretching our legs in the sun-bathed parking lot behind at the back of the building, clutching takeout coffee cups, chatting as we had been to pass the time, and as we reentered Dad’s room, we noticed his forehead strangely twitching and a sudden shift in the tone of his skin. Failing circulation had swollen his fingers into tumescent sausages and a grey shadow began to adumbrate his face. A purple stain that had earlier appeared at the top edge of his ear had spread ominously and from that moment his life leaked out of him apace. Outside it was a warm May afternoon with the long-dormant soil beginning to smell again of life and fecundity. The vernal light streamed in through the blinds in golden shafts, illuminating the antiseptic surfaces of linoleum and chrome. When Dad stopped breathing, my brother-in-law began to sob. The Tim Horton’s coffee cups still absurdly clutched in our hands, we stood there together wordlessly, my sister sobbing softly before we felt it was time to call in the duty nurse. It wasn’t long before Dad’s ashes too were trickling through my fingers onto the boxwoods and rose bushes of that little churchyard beside the highway, the trucks rumbling by and the sandwiches waiting in the reception room. The old Latin adage, Nos habebit humus– the earth shall have us–never seemed truer.

With the loss of my parents, a part of my world disappeared. I have myriad memories, of course, some good, some not so good, but the living, breathing individuals who conceived me are now irrevocably subsumed into the topsoil beneath a row of ornamental shrubs. Random, disjointed images keep flooding in from my preconscious childhood. I am playing with building blocks on a parquet floor. The sun streams in from between the curtains. My mother is reading in an armchair holding a cigarette. In the blue curls of her smoke, I notice for the first time teeming motes of dust – each in its own inscrutable trajectory yet somehow keeping its distance from its neighbour, each illuminated in golden light, a specific quality of light that continues to enchant me, the light of life, the light my father still marvelled at with his addled brain as it reflected off passing windshields onto the ceiling of the room in which he died, the warm glow of the sun returning to a northern spring after an intractable winter. I must have been gesturing somehow, open-mouthed and inchoate at the dust dancing in the shafts of sun, golden motes suspended in the peacock blue smoke of my mother’s exhalations, and she must have been watching me when she whispered conspiratorially –‘Die Piraten kommen!’– ‘the pirates are coming!’ I believe I burst into tears. Perhaps it was some magic that floated in the air that day. Perhaps it was an early warning. I didn’t know exactly what ‘Piraten’ meant but I suspected it might not be good. It was perhaps the first time I was made aware that in the present there could be some portent of the future.

When I think back on it, my parents at that time were probably quite sensitized to the notion of omens – the idea that there might be small signals in any given moment that presage cataclysm. They did, after all, as children survive the firebombings of Stuttgart and regaled me from an early age with horrific stories of charred corpses laid out on the cobblestones after the air raids, bodies incinerated to the size of bread loaves, and how all this ensued after a charismatic man by the name of Adolf Hitler somehow got into power and how things seemed so great at first with all the newfound pomp and ceremony, the trains running on time and those proud swastika flags flying everywhere before it all fell apart and the true nature of the evil that had been unleashed became increasingly apparent. If there is any truth in current theories about inherited trauma, epigenetically transferred, it might explain my own lifelong twitchiness despite a childhood in the safe, stuffy suburbs of Toronto. Perhaps this constitutes some as yet undescribed biological early warning system which sees the children of trauma survivors serve as societal antenna, predisposed toward vigilance for signs of emerging disaster. It’s all in the details really, the perceptions we experience from moment to moment, the flux of sensations we aggregate into worlds in which we find meaning. The thought we might inherit the trauma of our ancestors, despite not having experienced it directly, is unsettling. Do these shadows of the past predispose some of us to be canaries in the coal mine? The rustle of leaves might presage a storm, a mean-spirited remark–nascent fascism.

Which brings me to a tree, an ancient and immense Douglas fir, whose death I observed over the past few years down the road from where I lived for a time on a rather remote island in the twinkling Salish Sea. It is, or rather, was, an old-growth tree, a so-called veteran tree that somehow survived when the primeval forest all around it was felled and boomed off to distant sawmills by two or three generations of settler-colonists. Judging by its height and girth, this fir had been growing for well over four centuries and it was alive and well when I first encountered it in the early 1990s. Knowing it was there, even when I was far away, calmed me. I thought about it often in my East Village apartment, the din of sirens and the drunken arguments erupting outside my window. I imagined it slowly accreting its growth rings as it always had, the only sound the soughing of needles high in the crown, the branches there festooned with tufts of greenish-white lichen that quivered in the slightest breeze, the monumental, corrugated column of its trunk rising vertiginously into the winter mist, the fire-blackened bark of the enormous base upholstered here and there with cushions of viridian moss. In a tumultuous world, there was at least this: an ancient being somehow outlasting the depredations of capitalism – a vestige of a lost arboreal sublime, a nonhuman subject so incongruous with modernity, I could only gasp at its presence. It stood as a defiant exception, a marooned titan whose colossal kin had long ago disappeared into the horizon – a reminder of what there once was, of what once was possible before capitalism subsumed everything into board feet and dollar figures to be scribbled into ledgers.

But the old fir died and it did so rapidly. Unlike my parents, it wasn’t necessarily nearing the end of its natural life. For Douglas fir, a lifespan of 600 -800 years is not uncommon and there are records of up to 1400-year-old trees elsewhere on the coast. The signs of its demise were subtle at first –a slight browning of the needle tips after an uncharacteristically hot and witheringly dry summer. Though somewhat in the rain shadow of Vancouver Island, the island’s climate was considered maritime, generally characterized by a couple of fairly dry months in summer followed by 10 months of bucketing rain. The vegetation was classed as a temperate rainforest with all of the verdant mosses, glistening ferns and outsized fungi one might expect in such fecund conditions. Coastal Douglas fir is exquisitely adapted to this habitat and some of them number among the tallest and oldest trees in the world, comparable in size to the storied redwoods of California. Though the more accessible trees had long ago been plundered from the island, (which incidentally is named Cortes Island after one of the worst colonial plunderers of all time), there still remains a relic population of massive specimens that protrude here and there from the scraggly second-growth, looking like lignified watchtowers, the storm-wracked crowns often splintered and bent into expressionistic candelabras that are the favoured perches for bald eagles surveying the vastness of their airy domains.

Old-growth Douglas fir on Cortes Island

The fir down the road was a particularly magnificent example. A strange lumpy growth, Agarikon fungus, hung like a Venus of Willendorf under a massive transverse limb. Agarikon is regarded as ‘shaman’s bread’ by some First Nations. It often is curiously anthropomorphic and was esteemed for its ability to cure a range of diseases. The fungus had become an object of attention recently, when the celebrity mycologist, Paul Stamets sent a climber up the old tree to retrieve a sample. In his lab, Stamets extracted novel compounds potentially effective against such deadly human pathogens as anthrax and tuberculosis. Agarikon is symbiotic with old-growth Douglas fir and thus its survival is threatened as the ancient trees are exterminated. Less than 1% of the original old-growth fir forest remains along the eastern side of Vancouver Island, where it once dominated the landscape. The scant few veteran trees that survive are thus incredibly precious, not only as living reminders of a prelapsarian past but as an indispensable habitat for organisms such as Agarikon and many more yet to be catalogued. The very biggest trees support a rare arboreal soil constituting a unique ecosystem, a kind of microcosm populated by microorganisms and invertebrates unknown on the ground. We may be running out of time to find out whether one of these might contain, for example, some novel antibiotic or a cancer remedy. The last old firs are disappearing too fast.

Agarikon on fir some years before the decline The following summer was again unprecedentedly hot with temperatures almost daily breaking long-standing records and accompanied by a pitiless drought. The halcyon days of July and August I had been so used to, the cerulean dome of the sky, the gentle ocean breezes, were now occluded in apocalyptic orange with the noonday sun brooding over the silhouetted evergreens like a bloody eye or some celestial stoplight the planet had switched on to tell us all it had finally had enough. My throat rasped and my eyes seeped as I walked past the local campground listening to the muffled coughing of holidaymakers cowering in their zipped-up tents. The interior of the province was on fire and plumes of Stygian smoke billowed out from the mainland inlets and across the Desolation Sound, yes it’s actually called that, its waters now warm as urine, enshrouding the little island in eerie twilight, with skeins of acrid vapour clinging to any irregular surface for days then weeks.

As for the fir down the road, the dead needles that had only begun to be apparent the previous summer had now spread throughout the crown as if scorched by the poisoned breath of a basilisk. The Agarikon I had always admired as I passed beneath it had somehow just disappeared and I imagined its lumpy form shinnying down some moonless night to rejoin its long-lost colleagues in the mycelial underworld to maybe just wait this one out, to return, perhaps, once we’d made ourselves extinct to feast on our littered corpses.

Before these summers of smoke, Cortes had seemed a blissed-out sort of a place, at times annoyingly so when it bordered on the smug and self-congratulatory, a kind of loose compendium of anti-vaxxers, cagey-eyed preppers and Subaru seniors of the bird-watching sort in pastel Patagonia and sensible hiking boots, with a sprinkling of New Age utopianists, invariably Caucasian but with exuberantly died ethnic clothing. The demographic skews heavily toward flowing grey hair and old although there are always a few young, mostly itinerant, earth muffins, trying to make a go of it stocking shelves at the Food Co-op or doing laundry at the New Age retreat center. I garnered some incredulous looks when I let it be known I now needed two puffs from my asthma inhaler and a face mask just to make it through my daily run. Ruth, my normally robust wife, came down with chemical pneumonia from the incessant and unavoidable smoke that curled around our eaves and seeped into every cranny. She spent 3 weeks bed-ridden wheezing and coughing and heavily medicated during what should have been a restorative interlude in our hectic yearly schedule. But this is paradise! This will all pass! And indeed it was once a paradise, at least for those with the means to enjoy hand-crafted cedar houses nestled among whispering conifers with views of snow-capped mountains and azure expanses of the warmest tidewaters north of California. Humpback whales still cavort charismatically among the bellied sails of recreational yachters, living out their baby boomer dreams, we made it man! the more fitness-minded among them earnestly shovelling at the limpid waves as they recede into the horizon of their next carefully-curated kayak adventure. Yes there are stubborn pockets of rural poverty and the infrastructure is in serious decline, but nobody likes to talk about that for fear of a bummer vibe.

summer of smoke By the third summer, the old fir I had loved so dearly was really and truly dead. The branches once redolent with fragrant fans of blue-green needles now rattled like dry bones in the too-warm air with the lacework of their desiccated twigs tinged in an insalubrious orange from which a few dead cones still hung. Though I was heartbroken, the great tree’s demise seemed to pass mostly unnoticed. The ‘don’t worry be happy/the universe will provide’ cult of magical thinking is strongly enforced on Cortes Island, a kind of unquestioning loyalty to a failed utopia I have come across throughout the Pacific Northwest, despite the mental health emergencies, suicides by overdose and domestic abuse situations that plague the place. A brutal murder some years ago was met by a wall of silence from islanders, who seemed unable to accommodate this grim event into their idealized conceptions of the place, which I imagine resembles something off of a Celestial Seasonings tea label, populated by Smurfs, polka-dotted mushrooms and flaxen-haired children feeding absurdly tame wildlife.

For now, the imposing column of the fir’s great trunk still towers over the T-junction near my former home, but beneath its thick bark, the sap vessels no longer defy gravity to convey their nourishment to the needles high up in the crown, where the buzzing chloroplasts magically plucked photons from the sunbeams and enchanted the monumental scaffold of wood and bark that supported them into a living, breathing colossus. For hundreds of years, the fir endured, wracked by howling southeasters, wrenched by sodden oceanic snows, baked under the hyper-illuminating sunshine of dog day summers when the ground fires tore around its feet, each new generation of woodpeckers incessantly chiselling, the gnashing mandibles of numberless wood-boring insects, persistent and unforgiving, the endless fallout of microbes each seeking purchase to infest and spread rot – it endured all of this until a new variable was added into its equation for survival. This variable was borne a world away in Great Britain where the economic innovation of capitalism married the brand new idea of fossil-fuel-powered machinery, a union that was to unleash long-sequestered gases that began to heat up the atmosphere, a process that progressively accelerated and is now raging uncontrollably. I won’t bore anyone with the details –the record temperatures, the extremes of all kinds of weather–we are all aware of the grim and continuously unfolding litany of climate change, but at some moment, just a few years ago, that very old Douglas fir beside the country road on a little green island far out in the Salish Sea just couldn’t take it anymore and began to die. Others like it are dying too, all over the island and up and down the Pacific Coast, as are the giants in other parts of the world, the baobabs, the sequoias, even in hard-fought-for protected areas that assuaged us into thinking that at least these would somehow be safe. But they’re not safe, with the biggest and most venerable trees succumbing increasingly to a kind of aneurism elicited by the stress from the unprecedented extremes they (and we) are now experiencing, conditions that go far beyond what their genetically determined strategies for survival have equipped them to endure.

Perhaps someday no one will miss these old-growth Douglas firs that for so long made the coast of the Salish Sea a place unique to the world. In a generation or two, the big trees will likely all be gone as global heating continues apace, vanished into oblivion like the passenger pigeon, the Steller’s sea cow and the California grizzly bear before them. Though future generations might marvel at their images on the page or on the screen, or count the rings of a salvaged cross-section hanging in some museum, we will have lost the opportunity to experience the grandeur of these living, breathing beings whose lifespans once far exceeded our own, whose survival into the deep horizons of time once gave us the opportunity to contemplate the ephemerality of our existence. But I have stood beneath them, some of the last of them, when they were still lush and green, traced my eyes up along their towering trunks, and listened to the poetry of their whispering boughs. And for as long as I might continue to live, I will cherish their memory.

dwarf birches and tundra  suddenly – reindeer!

The morning broke grey and brooding outside the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station and after a quick breakfast, we were on the trail, hiking up Saana Fjell, guided by Erich Berger of the Finnish Bioart Society. The idea was to familiarize ourselves with the geology, ecology and cultural history of the vicinity so we could dive into our research plans as soon as possible.

The Australian bio-hacker, Oron Catts had already been here for a week to do some scouting for his group’s ‘Journey to the Post-Anthropogenic’ project. They planned to perform a comprehensive bio-archeological survey of the crash site of a German Junkers 88 bomber that came down on Saana in 1942, which included a metagenomic analysis of the plane’s debris field and a recreation of the crash trajectory using a remote-controlled drone.

debris field It wasn’t long before we passed the tree line where the mountain birches gave way to an expanse of open tundra sweeping out before us in a swath of russet heath and exposed rock, with quivering patches of silver cloud here and there snagged on the crenellations of the topography. As if on cue, a small herd of reindeer appeared over the crest of a nearby hill and galloped across our field of view, cocking their heads as they past us and then just as quickly melting into the gloom of the opposite horizon. It is hard to judge distances here in this cold desert. An unusual rock formation in the distance might be small and quite close by or enormous and very far away.

I felt for a moment as if I had been transported back to the Pleistocene, as the landscape I was looking at was what much of Europe and North America would have been like at the end of the last Ice Age, though (other than the reindeer) there wasn’t any of the charismatic megafauna such as the woolly mammoth and the cave lions I would have had to concern myself with back then. Semi-domesticated, reindeer have sustained the local Sami people since ancient times and they are of the few creatures (other than snails) to manufacture the enzyme lichenase, enabling them to survive on lichen during the winter months.

How this delicate ecological balance will be affected by climate change is unclear but to my mind it doesn’t look good. Lichens exist in fairly specific temperature and humidity conditions and in Kilpisjärvi many are symbiotic with the birch trees, themselves a cold-dependent species. A continued warming trend in this region is bound to mean diminishment of suitable reindeer habitat. This has already occurred in North America, where the closely related Woodland Caribou has steadily disappeared from the southern portions of its range.

Standing in the middle of this iconic subarctic landscape, it is hard to imagine rapid changes occurring. For thousands of years, the processes shaping it have been gradual and incremental – the slow scouring of glaciers advancing and retreating, the infiltration of frost with its insidious heaving and splitting, the seasonal flows of meltwater into the lakes and rivers. The cold accentuates the sense of Deep Time here. Rocks dragged by ancient ice flows sit solemnly in place as if they stopped moving only yesterday. The sparse, slow growing vegetation is no match for the overwhelmingly geologic feeling of the place. Even minor disturbances stay visible for centuries.

But add even a small degree of warming and there would be potentially huge changes. Vegetative growth would ramp up, allowing trees to flourish in areas that were once windswept barrens. It is easy to imagine the slopes of Saana darkening as the Scotch Pine (Pinus sylvestris), now found only intermittently in the Kilpisjärvi area but quite common further south, finds conditions more suitable to it and becomes a dominant species. True tundra and the flora and fauna that depend on it could disappear from the area entirely.

lone Scots pine Fast-forward a little further and there could be a whole host of new species that find the once frigid environs of Kilpisjärvi newly tolerable. A good many of these are likely to be weeds, which thrive on man-made disturbance. Investigating the grounds around the research station, I soon found a small clump of English plantain (Plantago major) a cosmopolitan weed, dubbed the ‘white man’s footprint’ by North American First Nations, who noticed it growing wherever European colonizers had disturbed the original ecosystem. The humble plantain is just the beginning. I predict that larger weed species will soon be gaining a foothold at Kilpisjärvi; their seeds imported on tire treads or blown in with the wind.

I wondered how it might look here when Ailanthus altissima, a tree variously known as the ‘Ghetto Palm’ or ‘Tree of Heaven,’ moves into the Finnish subarctic. Originally from China, Ailanthus is exuberantly invasive, and has already moved into ruderal (ruin) ecologies throughout the world without any signs of stopping. This tree has the astounding ability to feed off concrete, allowing it to thrive in cracks in pavement, the roofs and facades of under-maintained buildings and pretty much any other place its myriad seeds are able to lodge themselves long enough to germinate.

Ailanthus trees As the global south becomes uninhabitable due to increasing drought, wildfire and relentless heat, it isn’t hard to imagine a newly temperate Kilpisjärvi becoming a major magnet for climate refugees, human and non-human. Higher annual temperatures, as well as attracting different flora and fauna, could make the cultivation of cereal crops a possibility and perhaps other kinds of intensive agriculture, now more characteristic of Central Europe. This could transform the wild, transhumance landscape into a ‘Kulturlandschaft,’ the subarctic wilderness giving way to ploughed fields, perhaps even orchards. There might be a property boom as the open range lands once suitable only for reindeer husbandry become hosts to cash crops and housing estates. The effect on the traditional Sami lifestyle would be incalculable.

A climate-changed Kilpisjärvi would be a kind of ‘hyperecology’– a co-mingling of adaptive, cosmopolitan weeds, perhaps a few resilient local organisms and a steady in-migration of biota from the south. Outside the national parks and reserves, post-climate change nature will have even less of a free hand. There is massive industrial development afoot for Lapland, particularly mining and its ancillary industries which threaten to blight vast tracts of the relatively pristine landscape with open pit mines, tailings ponds and processing infrastructure, which, as well as inevitably introducing all sorts of pollution will create a new terrain vague of slag heaps and factory wastelands. These ‘brownfields,’ ubiquitous in much of the industrialized world are the preferred habitats of the globally distributed ragamuffin flora: Ailanthus, Buddlea and Robinia, which find the toxic and impoverished soils to their liking.

Industrialized, intensely cultivated and densely populated, the Kilpisjärvi of the not-to-distant future might look strangely familiar to any present day resident of a more temperate latitude. Yet what has been predictable there for so long will soon become much more extreme. We may all find ourselves moving north.

But climate change isn’t likely to stop at this arbitrary point. The heat will likely continue to build, especially if mankind continues dumping carbon into the atmosphere and particularly if the much feared ‘runaway greenhouse’ effect kicks in. What then for Kilpisjärvi? The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum that happened some 55 million years ago gives us a clue. In those days, the weather north of the Arctic circle was sultry and humid the year round. In addition to the Sciadopitys trees I described in my previous posting, vast swamp forests of Metasequoia and Taxodium spread out across the far north of Eurasia and North America, with turtles and crocodiles plying through the black water and mire. It would have resembled the bayou country of Louisiana or subtropical China, with snow and ice pretty much non-existent, a far cry from the frigid Kilpisjärvi of today, which can be icebound 200 days a year.

Eocene landscape Northern regions are well on track for a repeat of these subtropical conditions according to the most agreed upon climate change models, which predict an up to 4 degree Celsius rise globally by the end of the century, with a strong likelihood that changes in high latitudes will be more extreme. Though the biota will surely be more impoverished than it was in the Eocene, not having had anywhere near as much time to evolve, an anthropogenically tropical Lapland would be a mind-boggling yet disturbingly real possibility.

Though our species’ effect on climate can (and will) precipitate far-reaching changes in areas like Kilpisjärvi, there are many planetary processes playing out over which we have no control. The evolution of biota over Deep Time is as much happenstance as forward movement, with periods of great flourishing such as the infamous ‘Cambrian Explosion’ interspersed with ‘reversal’ or mass extinction, either organically or extraterrestrially engendered, which often obliterate whole classes of once dominant organisms and provide opportunities for minor ones to come out of the wings.

Past instigators of mass extinction have included: asteroid impacts, widespread volcanic eruptions with concomitant ocean acidification, even the evolution of photosynthesis by cyanobacteria, which released the toxic gas oxygen into the atmosphere to the detriment of the once dominant anaerobes. Any and all of these scenarios will likely play out again somewhere in the fullness of Deep Time, but barring the elimination of all life on the planet, it is worth speculating on the impact such upheavals would have on the vegetated landscape.

For example, what would happen if flowering plants, also known as angiosperms, dramatically declined, perhaps taken out by some pandemic or selective evolutionary pressure? They’ve really only been common since the Cretaceous and it isn’t hard to imagine Kilpisjärvi’s abundant so-called ‘lower’ plants – mosses, club mosses and liverworts, moving into the vacuum and attaining gigantic proportions, as was the case during in the coal swamps of the Carboniferous Period.

Neo-Kilpisjärvi with giant club mosses A reduction in the availability of sunlight due to volcanic ash or widespread dust storms could have equally bizarre consequences. With green plants and algea in decline because of the challenge to photosynthesis, there would be a selective advantage for fungi, which might take over Kilpisjärvi forming bizarre, colossal structures as they did during the Devonian Period, some 400 million years ago, and again during the mayhem of the Permian mass extinction. Whether our own species would survive under such extreme and alien conditions is an open question, but life of some sort is almost certain to find a way. Perhaps fungi will regroup to form the planet’s supreme intelligence. Some would say, they already have!

It is this last point that gives me a vestige of hope. We Homo sapiens are a problematic creature, a classic, invasive species that thrives on disturbance, tends toward monoculture and displaces competing biota from its habitat. Yet in the overall scheme of things we are likely to be a transient phenomenon. We will either precipitate our own extinction, (and if the surviving ecosystems of the planet could sigh in relief, they surely would!), or we will find a way to live within our ecological means and develop a more equitable arrangement with the fellow denizens of the biosphere. My stay at the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station offered me the ideal vantage point to consider this conundrum. What we are in now is not so much of a ‘watershed’ moment but more of a ‘timeshed’ moment!

Neo-Kilpisjärvi with giant fungi

Saana Fjell – Kilpisjärvi (in a warmer season!)

Sciadopitys in Helsinki Botanical Garden

What will the future look like?

A reasonable question and one which the human race has spent a long time thinking about.

I felt quite honoured to be asked to participate in this year’s ‘Field_Notes – Deep Time’ artist’s residency which took place this past September at the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station in the spectacular subarctic environs of Finnish Lapland. I was part of a working group led by my pals Liz Ellsworth and Jamie Kruse and our mission was to explore the concept of ‘Deep Futures in the Making.’

In many ways the bleak solitude of Kilpisjärvi proved the perfect vantage point from which to delve into ‘Deep Futures,’ both due to the majestic, timeless feeling of the landscape but also the unique vulnerability of the fragile ecosystem, which like others at high latitudes is likely to suffer disproportionately from the effects of anthropogenic climate change.

Perhaps biting off more than I could chew, I tasked myself with compiling what I called a ‘Speculative Botany’ for the future of subarctic Finland, based on what is there now and what is likely to happen in both the near and the long term.

The effects of global warming on arctic and subarctic ecosystems are already proceeding apace and in addition to the well known images of abject polar bears stranded on rapidly melting ice flows, there have been many other effects on northern biota. Here in North America, more southerly species such as robins (Turdus migratorius) and Pacific salmon are colonizing high arctic latitudes. A little to the south, vast tracts of Rocky Mountain forest are turning brown under an unprecedented onslaught of pine beetles, whose numbers are no longer kept in check due to milder winters and hotter summers.

So what about ‘Deep Futures?’

Environmental conditions are changing so rapidly that I frequently get the feeling I have already woken up Rip Van Winkle style in some deep future, where the things I have long taken for granted are no longer recognizable. Like the frogs that used to teem in the ditches of my suburban Toronto childhood. They are now disappearing worldwide, their once exuberant choruses silenced by a strange new fungal pandemic. The Western black rhino has just gone extinct – all of them. Gone. Wiped off the earth by relentless poaching. Neither you nor I nor anybody else will ever have a chance to see one. We blew it. And countless other species are on the brink of the same fate.

Climatologically, the obvious effects of anthropogenic warming are now everywhere and we are seeing weather events that are routinely more extreme than anything experienced in the recent past, though they have long been in our collective imagination. Reminiscent of J.G. Ballard’s dystopian 1960’s fantasies – ‘The Drowned World’ and ‘The Wind from Nowhere’ we now live in a world where ‘superstorms,’ extreme flooding and the disappearance of Arctic sea ice are the new normal

With the scientific consensus emerging that global temperatures will continue to rise by at least 4 degrees C by the end of the century, I wondered what might happen at Kilpisjärvi, which presently finds itself in a delicate mountain birch forest ecosystem, where normally the snow doesn’t melt until June. Already it is clear that with less severe winters, plant productivity and abundance in many far northern areas has significantly increased.

What novel re-groupings, permutations and combinations might occur as the climate of Kilpisjärvi warms up? Will the existing plants grow more rampantly or will they begin to find the new conditions intolerable and fade from the landscape? There are some basic principles I thought I could extrapolate from. For example, rapid climate change is likely to favour generalists, often weed species, capable of riding out a wide variety of conditions and quickly colonizing disturbed habitats. Cold-loving, habitat specific specialists will have a much more difficult time and would disappear from many of their more southern haunts.

the future of arctic fauna?

How long might it take for major changes in the biota to occur? There are so many things to consider. For example, birds can colonize newly habitats quickly, which in turn will be a vector for certain plants whose seeds travel long distances inside their digestive tracts to be deposited on new terrains. Wind borne seeds and spores are likewise rapidly distributed. We humans are perhaps the greatest agents for the dispersal of species, transporting them deliberately or by accident, through the shipment of goods, gardening and even on the soles of our shoes. The deeper the future, the more daunting the range of possibilities, so I thought it reasonable to start with the situation in Kilpisjärvi at the present day and project onward into deeper and deeper horizons of time, with a corresponding decrease in certainty.

I am an artist, not a scientist, so I knew my speculations would be more qualitative than quantitative, but I figured it was worth trying to extrapolate obvious trends and imagine how they might unfold in both the near and long term.

A few hours after first touching down in Helsinki and pleasantly catatonic from the jet lag, I took a long walk through the venerable Kaisaniemi Botanical Garden. It is a habit of mine to visit the botanical garden of any city that is new to me and I was curious to see what the Finns managed to cultivate at such a high northern latitude. And I wanted to establish some sort of a baseline for what would typically constitute northern flora. Admittedly Helsinki is a good deal further south than Kilpisjärvi but is nevertheless considered the world’s most northerly metropolitan area and I reckoned the climate of Kilpisjärvi would begin to drift toward that of present day Helsinki as the planet continues to warm. Established in the early 1800’s Kaisaniemi has the agreeable and lush historicity of an old, lovingly maintained park, a world within itself of specimen groves and steamy glasshouses, where the casual stroller or the committed anomophile can each commune with the diverse array of the botanically possible.

From the very beginning gardeners have always pushed the envelope of what can be cultivated in a given climatic zone and Kaianiemi is no exception. For example there is an enormous walnut (Juglans regia) tree, sprawling and laden with nuts far to the north of its usual more temperate haunts. I was delighted to see one of my favourite living fossils, the monotypic Sciadopitys verticella, commonly referred to as the Japanese umbrella pine, as it is now only native to a small area of Japan. Yet during the Eocene Thermal Maximum 50 million years ago there were whole forests of these trees in the vicinity of what is now Finland and the resin they produced was so ubiquitous it makes up the bulk of the area’s famous Baltic amber. During that long ago time, the average temperatures on the earth were extemely high, as high, in fact, as it is expected to rise again within this next century, due to man-made global warming. Could it be that Sciadopitys might one day hop Kaianiemi’s garden fence and make itself at home again in the forests around a newly tepid Baltic? I wonder…

In contrast to how compact everything generally seems to a North American traveling through Europe, the distances in Finland are quite vast. The day after arriving in Helsinki, I was en route on the seven hour trek to Kilpisjärvi, which began with a one hour flight north to Rovaniemi,‘the hometown of Santa’ and the capital of Lapland (not necessarily in that order), followed by a six hour bus ride on a two lane highway to almost the 70th parallel. As the scenery passed by and the tires hummed and the vegetation grew more sparse, we were able to acquainted with each other and start thinking about how we might address a topic as vast as ‘Deep Time.’

On a more prosaic note: I loved the bizarre and über-Nordic aesthetic of the coffee-shops in roadside Lapland, a few of which we were able to sample on the bus ride to and from Kipisjärvi. Amazingly, there is a pension for Thai food up here. Their secret ingredient – reindeer meat! And by the way, the wood carvers are definitely on drugs – perhaps some taiga version of the magic mushroom… Check out the whacky wooden dwarfs that are the regional specialty. The carving style out-Seusses Doctor Seuss! Oh those long winters! I think I understand the flying reindeer now…

An hour or so from our destination, and the landscape morphed into a vast, misty expanse of exposed rock, russet heath lands and dwarf birches, their branches stripped of all but a few remaining yellow leaves despite it being only mid September – still, as far as the calendar is concerned – summer! When we finally pulled into the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station it was almost dark. The air had a thin, alpine quality about it and the massive silhouette of the Saana fjell loomed over us like some giant recumbent beast. We were told we’d be climbing it the next day and we collapsed into our beds…

Sanaa socked in with cloud

Fuligo septica in my back yard

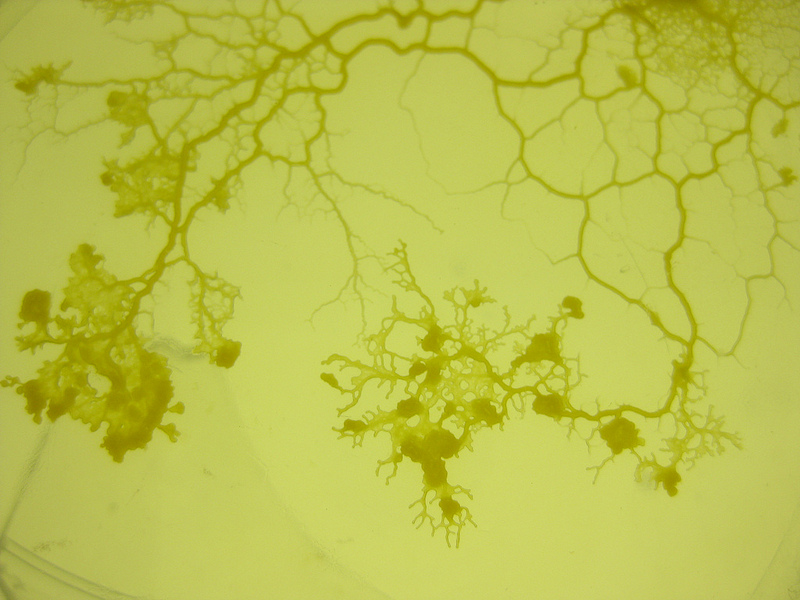

Physarum polycephalum close up

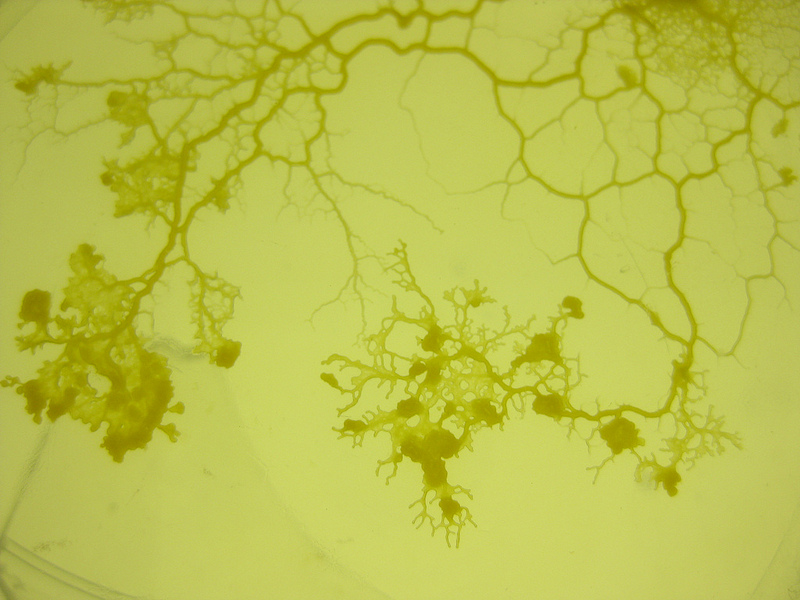

Those of you who’ve followed my blog for a while will know I am fascinated by the intellectual capabilities of slime moulds…

This is the time of year when the dark coniferous forests near my house get brightened up by their white and yellow blobs of sentient goo. Around here, they are mostly the common slime mould Fuligo septica – otherwise known as ‘Dog Vomit slime mould,’ a rather harsh name, in my opinion, for such an engaging life form.

Far from being vomit or mould, these slimy masses are actually swarms of social amoebae that have combined their protoplasm and nuclei into a single super-organism called a plasmodium.

Once formed, the plasmodium creeps along the forest floor until it reaches a tree stump or log, at which point it climbs to a high enough vantage point from where it releases its spores into the slightly more active air. These drift, land, and eventually germinate into another generation tiny amoebas that one day will seek each other out, meld together and then start their complicated social migration process again.

This is all very fascinating, but the reason slime moulds have been the subject of such intensive research is that their plasmodial masses show an uncanny ability to solve computational problems – which is all the more remarkable given that slime mould has neither brain or a nervous system and its constituent amoebae are about as rudimentary a life form as you can get. But when large numbers of these simple beings are networked into a swarm, the principle of emergence takes over and we begin to see a unified intelligence. The rules governing emergence are fairly simple – as long as each individual is aware of and able to exchange basic sensory information with its neighbours, stimuli can be transmitted throughout the network, which can then react as a sentient whole, flowing toward attractants or away from danger.

This simple yet powerful mechanism is behind the flocking of birds, the flow of traffic and the evolution of memes on the internet. It is a non-hierarchical, ‘ur’-intelligence, an organizing tendency imbued in the very vibrancy of matter itself.

The lab rat of the slime mould world is the easy-to-raise species Physarum polycephalum and as such it has been the subject of much experimentation. Lured by oatmeal flakes, Physarum can outperform robots in solving mazes and it will figure out mathematically complex problems such as how to most efficiently connect an arrangement of arbitrary points, making it astonishingly good at designing highway networks and other mesh-like systems. Though brainless, Physarum has a rudimentary spatial memory. It recognizes where it has already explored by sensing the slime trails it has left behind, allowing it to focus its foraging energy on covering new ground.

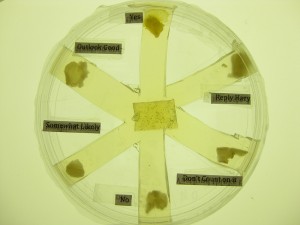

Inspired by my time hanging around with the bio-geeks at Brooklyn’s GENSPACE, I decided to put old Physarum to the test by giving it some problems I thought worthy of its impressive powers.

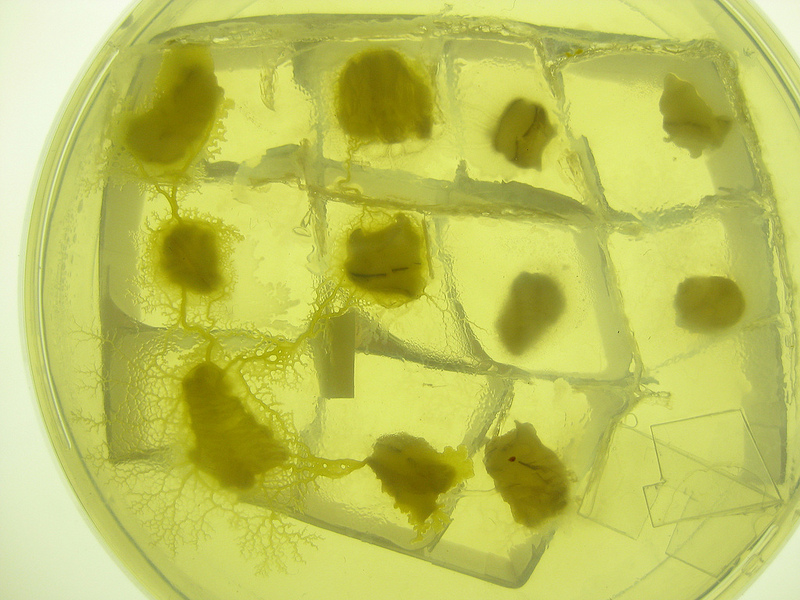

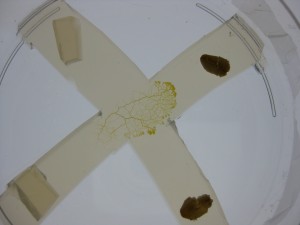

slime mould navigating a model of an IKEA 1) The IKEA vexation:

For years I have been irked by IKEA stores. What is the most efficient way to navigate through one of them? I find IKEA to be especially frustrating and always have had trouble finding my way toward the exit without being overcome by an anxious ‘trapped’ feeling. For me, IKEA is prime habitat for what it called the Gruen transfer – a deliberate architectural strategy aimed at disorienting people in shopping malls; an invocation of spatial confusion that makes us lose track of our original intentions and buy stuff we don’t need. I wondered if the slime mould could resist such distractions and efficiently find its way through an IKEA without getting sidetracked? To put this to the test, I built a tiny petri-dish sized model of the floor plan of the IKEA, modeled on the store in Richmond, British Columbia, which is more or less typical. Each department was baited with an oatmeal flake and I plunked a little bit of Physarum culture down near the store’s entrance to see what it could do.

slime mould says ‘yes!’

second choice ‘hazy!’

at the moment of ‘yes or no?’

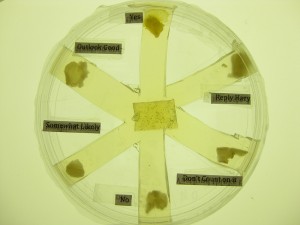

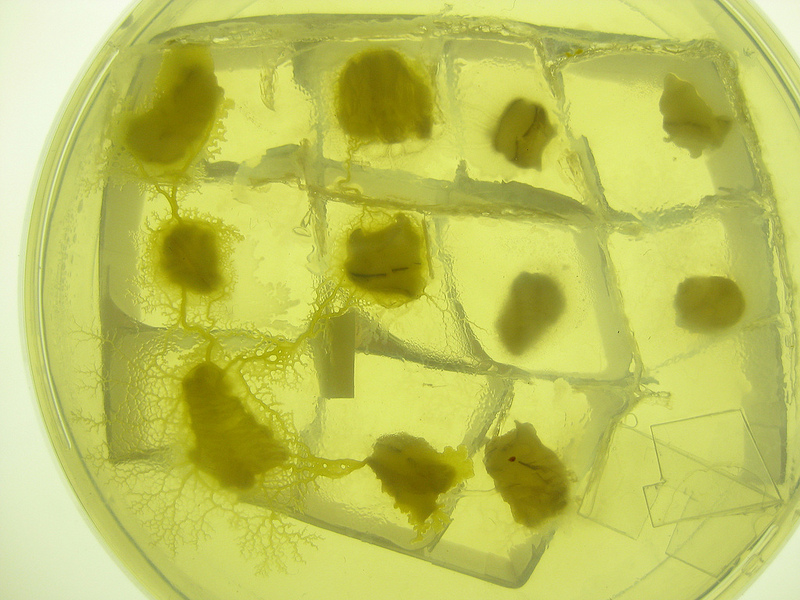

2) The Future is out there:

Decisions involving the future are hard for me to make, especially if there are a lot of equal seeming options. Throughout history, we’ve consulted soothsayers, fortune tellers and ouija boards in hopes we might get some guidance on how to choose between those many forks we encounter in life’s road. I’ve often despair and then make a seemingly random choice. If slime moulds are so good at solving problems in the here and now, how might they do in sussing out what hasn’t yet happened? Could they help me ‘Magic 8-Ball’ style make decisions on what to do next? Well, I was a little too clumsy to build a proper ‘8-Ball’, but I managed to make a reasonably convincing ‘6-Ball’ simulacrum, by cutting six (approximately identical) radial paths into the agar of a petri dish and having the slime mould choose which one it wanted to go down. I baited each ‘choice’ with a flake of oatmeal and labelled them: ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘outlook good,’ ‘reply hazy,’ ‘somewhat likely,’ and ‘don’t count on it!’ I’d ask the slime mould a (secret) question then wait a few hours to see what it decided.

Well those of you who have had scientific training are probably about to bust a blood vessel about now, but bear with me!

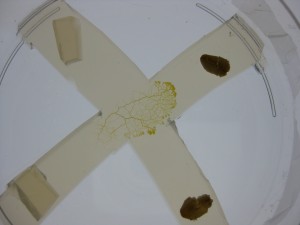

ballistic behaviour Perhaps predictably, the IKEA ‘maze’ problem was quickly solved by Physarum. It relentlessly streamed from one ‘department’ to the next in search of its oatmeal rewards and within a couple of days, it arrived at the exit hungry for more. This is a very basic slime mould-solvable problem. Physarum tends to behave in what is called a ‘ballistic’ manner; once they have sensed a stimulus they will try to flow toward it taking the most direct route possible.

Except when they don’t

Because unlike a non-sentient being, slime mould will often abort its migration toward an attractant, if it senses a rival has gotten there first. Sometimes though, competitors will merge into one happy super organism and share the the love and the bounty.

inputs A and B seeking oatmeal

A and B combining to one output

This makes for some interesting possibilities for ‘non-digital’ logic. Let’s say we place slime moulds, (let’s call them ‘A’ and ‘B’) in each of the two forks of a ‘Y’ shaped path and put an oatmeal flake in the remaining leg. If the slime moulds were to behave consistently that is to say ‘digitally’, you would have the basis for what is called an Exclusive ‘OR’ gate, a common component of computer logic. There has been some great research done on this by Andrew Adamatzky at the University of the West of England.

Given the slime moulds’ usual aversion to the presence of a rival, the one that gets to the bait first will dissuade the other. So in logic gate terms the presence of ‘A’ or ‘B’ (the inputs) will generate an output, i.e. either ‘A’ or ‘B’ gets to the oatmeal.

‘A’ and ‘B’ can’t both reach the oatmeal because the presence of one will (most of the time) repel the other, so the gate is considered ‘exclusive.’

But because slime moulds, though simple, are living things, with their own agency, they don’t always do what we expect. When the slime moulds ‘A’ and ‘B’ break convention and flow together to share the oatmeal, the logic gate becomes ‘non-exclusive,’ i.e input ‘A’ or ‘B’ or both can appear as outputs. Sometimes even that doesn’t happen and a slime mould gets distracted and decides to loiter around the perimeter of the petri dish, boycotting the experiment despite the presence of oatmeal. Who knows why? Are they following their bliss? Or are they just confused? To my mind, these ‘exceptions’ to the behaviour we deem ‘logical’ are the most interesting results. If we develop a new class of biological computers based on slime mould logic, the outputs generated might have a charming and useful variability. This could be used to more closely emulate the real world ‘twitchiness’ of such social phenomena as how people behave in the marketplace (they don’t always act rationally or in their self interest), or how they participate in riots or elections, which are also less than rational processes.

this time- both outputs are generated! And as for predicting my future, the slime mould oracle was initially quite decisive. It answered my first (secret) question with a resounding ‘Yes,’ but then started creeping around to investigate other nearby possibilities. To me that seems like a perfectly reasonable approach.

Vancouver Island highway scene At this ardently bright juncture of the year, there is something quite delightful about gazing up into the cool, rustling canopy of overhanging trees. It is a very deep memory for me. I must have been an infant, lying on the back bench seat of my parents’ old Buick, gazing up through the rear window at the dark tunnel of foliage billowing overhead, flashing here and there with orange bursts of interpenetrating sunlight. The dust from the road was starting to smell like the softer evening version of itself and the roadside insects, cicadas probably, hissed in their enormous, invisible numbers.

In my recent journeys between England and Canada, I have been struck by the contrast in attitudes toward what one might call ‘arboreal heritage’ between the two places. When driving on Vancouver Island I am inevitably torn between throwing up and crying whenever I see, as I almost always do, some of the last old growth Douglas firs (Pseudotsuga menziesii) getting hauled down the highway on some logging truck. Their rate of felling has been accelerated recently by a growth in demand from overseas, particularly Chinese, markets and the provincial government’s stupendously short-sighted decision to relax restrictions on the exporting of raw logs.

Each one of these ancient trees is a monument to the passing of centuries, a lynchpin around which complex ecological processes have evolved and yet we are losing the last primeval stands right at this very moment. To see one of those loaded trucks is like witnessing the carcass of a blue whale or a rhinoceros trucked off to a dog food factory but what more is there to be said? We have pointed our fingers yet the market economy has triumphed and the trees continue to fall. Soon all there will be left is a lingering sense of shame until that too eventually disappears. Outside a few relic specimens that happen to find themselves inside parks, the ancient fir groves of Vancouver Island will soon be obliterated. The Island Timberlands company continues to be a key player in this campaign of ecological extermination and is specifically targeting the large old trees on its vast private holdings to service an international market growing all the more lucrative as the global supply of first growth trees plummets.

this linden (lime) tree has been coppiced since at least the 13th century! While British Columbia has been embarrassingly and heartbreakingly remiss in its protection of Vancouver Island’s ancient firs, there are pockets of silvicultural enlightenment elsewhere in the world that can restore one’s faith in humanity. Last month Ruth and I spent a memorable afternoon at the Westonbirt Arboretum and got introduced to some of its innovative programs by director Simon Toomer. It may sound odd, but one of the highlights of our tour was seeing the manifold stumps of a recently harvested lime (Tilia sp.) tree, which has been harvested using the coppicing technique since at least the 13th century. The tree itself, which has spread out into about 60 individual stems, could be over a thousand years old! Coppicing (periodic cutting from regrowth regenerated from stumps or ‘stools’) is an ancient technique, suitable for a variety of mostly broadleaf trees, which paradoxically causes them to live much longer than if they were allowed to grow uncut. The practice periodically opens up parts of the forest canopy, allowing for an influx of light and a host of species dependent on brighter conditons, which enhances diversity in the forest, without massacring the entire structure over a large landscape as is done during industrial clear cutting. In British Columbia, it would definitely be worth testing out large-scale coppice management of Big-leafed maple (Acer macrophyllum) and Red Alder (Alnus rubra), both of which are capable of rapid regeneration from stumps and which have the potential to produce a range of sustainable wood products.

Westonbirt is also engaged in pioneering research on how forests will be affected by climate change and have initiated a series of long term trials of trees, hailing from a spectrum of locations, from the southern to northern parts of their present day ranges. If conditions continue to heat up, it is likely that trees evolving in more southerly latitudes will increasingly thrive within the British landscape, while more cold-adapted ones will only do well at higher latitudes and altitudes.

Back in British Columbia, I am beginning to draw similar conclusions. Though still in its early stages, the initial results of my Cortes Island ‘Neo-Eocene’ project indicate that some tree species now native to more southerly latitudes, such as Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and Metasequoia (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) might actually grow faster under West Coast Canadian conditions than varieties currently prescribed for re-forestation, such as Western Red cedar (Thuja plicata). The difference is likely to intensify as northern climates continue to heat up. Climate warming is already causing massive mortality in northern populations of the native yellow cypress/cedar (Cupressus nootkatensis), because spring snow cover is no longer thick enough to protect their delicate roots from late frosts.

The premise of ‘Neo-Eocene’ is that we need to examine longer, more geologic time spans for guidance on how ecosystems might deal with the rapidly unfolding effects of anthropogenic climate change. During the Eocene Thermal Maximum, some 55 million years ago, taxa such as Sequoia, Metasequoia and Gingko, which are now extremely limited in natural distribution, did in fact range far into northern latitudes; so it makes sense to experimentally reintroduce them, especially to areas where the extant forest has been compromised by industrial logging or climate-change induced die-offs. Our concept of what is considered ‘native’ needs to be rethought, and we’ll have to expand our definition to encompass organisms that have been ‘prehistorically native.’ So bring on the Giant Ground Sloths! If only we could!

Apropos of the topic of ‘Deep Time,’ I have been invited to Finland this September to participate in the Field_Notes – Deep Time residency in subarctic Kilpisjärvi Finland. Along with the Smudge Studio folks and a bunch of other amazing people, I’ll be considering how developing a more ‘geologic’ perspective might help assess our trajectory into the deep future. As the world heats up again to levels seen only in the geologic, pre-human past, how will we cope? How long will it take for a subarctic place like Kilpisjärvi to feel like Lisbon or Lagos? Will more southerly latitudes, once temperate and agriculturally productive, become thermally uninhabitable? Will climate refugees, human and non-human, flood into the formally frigid northland? How might the northern biota adapt? Or can it? Anyway, I am endlessly excited.

Davidia tree in Wiltshire Another refugee from deep time is the wonderfully flamboyant Davidia tree, which dates back all the way to the Miocene, when it was much more widely distributed. Miraculously, a few groves somehow survived the intervening millennia deep within the gorges of Szechuan China. The tree with its magnificent, floppy white bracts, which some liken to handkerchiefs or doves, caught the attention of a French missionary, Abbé Armand David. He sent some dried samples back to Europe and a botanical sensation promptly ensued. It wasn’t long before a plant hunters from England and the United States were dispatched to what was then a very remote area, charged with collecting Davidia seeds for cultivation. In the Davidia’s case, this proved to be a boon for the global population as there are now fine specimens of the tree flourishing in parks and gardens throughout the temperate zones of the world, thanks to those early batches of seed. Davidia, as is the case with Metasequoia and Gingko are considered vulnerable in their native habitat, and it is only through their widespread cultivation outside the small territories in which they still naturally occur that their future remains assured. Yet who knows? These curious and obscure trees might contain within them a genetic willingness to reestablish themselves in vast swathes of the northern hemisphere, as the climate of the distant geologic past becomes the climate of the not so distant future. Here is a picture of the biggest Davidia I have ever seen. It was in full, glorious bloom, when I visited the the grounds of a lovely Wiltshire property, owned by the Guinness family. Judging by its size, this specimen seems likely to have been one of the first ones propagated – an ambassador of sorts from the distant geologic past that once again has a role to play in the beauty of the wider world.

a flurry of doves or handkerchiefs!

The old growth forests of Vancouver Island are almost gone. The overwhelming majority have already been cut down and in many cases what has grown back has been whacked back several times over, leaving us with a landscape which, while wooded and at times even beautiful, is basically a ravaged, stunted version of something that was once truly glorious.

On Cortes Island, British Columbia where I live, the forest is an unusual ‘dry rainforest’ known as the (the very dry eastern variant of the Coastal Hemlock zone), which has less than 1% its original forest cover remaining. Some of the finer groves are about to be razed, put on container ships and shipped overseas by a company called Island Timberlands, itself set to be partially bought out by the $480 billion China Investment Corporation (CIC). Under the rules of globalized, neo-liberal economics this is all perfectly legal and in fact encouraged by a compliant provincial government who have been major recipients of forest industry campaign donations during the last election. To reward their benefactors, the BC government further gutted the already weak legislation governing the protection of the environment on private forest lands to the point where it has essentially been left to regulate itself.

The destruction of Cortes’ forests might have started any day now, were it not for outraged citizens physically putting themselves on the line to prevent Island Timberlands from starting its logging operations. This is truly a last ditch effort, noble but doomed to failure unless someone in political power steps up to the plate and comes up with a way of saving this piece of a vanishing ecological heritage.

Yet in a bizarre mirroring effect, as the real world’s ancient forests disappear before our eyes, they proliferate like never before in the simulacrum world of video games and fantasy films. From The Hobbit to World of Warcraft the old growth archetype lives on as a majestic and mysterious backdrop for the exploits of our avatars and fictional heroes. We are drawn to the these places in our imagination, yet can’t prevent ourselves from destroying the last examples of the real thing. Perhaps we will come to prefer them pixellated. Perhaps we already do.

|

|