|

|

a life companion To be, just for a moment, in the mind of another is a worthy ambition – all the more so if the being whose head you want to get inside is a non-human being.

As I type these words, my box turtle Marmaduke is staring up at me from the floor beneath my desk. Having lived with him for than 48 years, I know this particular expression means something: very likely that he has noticed his dinner bowl is empty or that the leftover food therein has dried out. In his own reptilian way, he is telling me that this will not do!

After the very many years of our relationship, I have learned to recognize that look.

But what would it be like to be him? To look out at the world through those baleful, red eyes? To truly experience it all from his point of view, without the baggage of anthropomorphism so drilled into us through too many childhood Disney films?

I am not, nor ever will I be – a turtle, though I would very much like to understand something of a turtle’s subjectivity.

The bio-semiotician Jakob von Uexküll made great strides in such imaginings, laying out a detailed framework on how we might perceive the perceptual worlds of the animal other.

He begins his (1934) ‘A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Man’ with an entreaty to participate in a thought experiment, to imagine ourselves wandering through a flower-strewn meadow, blowing:

a soap bubble around each creature to represent its own world, filled with it perceptions that it alone knows. When we ourselves then step into one of these bubbles, the familiar meadow is transformed. Many of its colourful features disappear, others no longer belong together but appear in new relationships. A new world comes into being. Through the bubble we see the world as it appears to the animals themselves, not as it appears to us. This we call the phenomenal world or the self world of the animal.

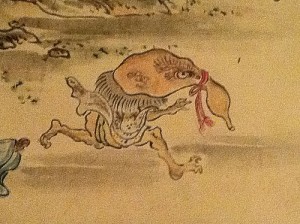

Von Uexküll goes on to visualize what the world might look like from the point of view of a host of creatures – ticks, sea urchins, jackdaws, flies, dogs, chickens – each living within its Umwelt; the German translating literally as ‘surrounding world’, of a given subject, perceived and interacted with through its own organs. This seminal text, a combination of astute scientific observation and self-described ‘ramblings’, influenced everyone from Deleuze to contemporary UX designers. In it, Von Uexküll challenges us to reconsider the universe from the non-human point of view, which is after all something people have been obsessed with since our very beginnings. Even in the earliest cave paintings, we see a longing to inhabit, to become the animal; at once the object and the subject of our desire; much more than simply an aesthetic preoccupation. Depictions of becomings animal, of interstitial states, of hybridity, have appeared throughout human culture, from the falcon-headed Egyptian god Horus, to the Minotaur, to the shape-shifting Japanese tanuki, to the vampires, werewolves, the princes disguised as frogs, Batman, Spiderman – you name it!

We wonder what it might be like to be an eagle, soaring over mountain peaks, its eyes far superior to ours, scanning the barren wastelands for a glimpse of the scurrying marmot? Or to put ourselves just for moment, inside the head of our trusted dog, for whom the air we breath is redolent of convoluted odour narratives and invisible signifiers.

The minds of our pets are frequent objects of our narcissistic conjecture: What do they think of us? Do they love us? Do they miss us when we are away? and so on.

Though we share our homes and lives with them, and have substantially altered their genetics to suit our sense of ‘what an animal should be like’, the power relationships between us aren’t completely one-sided, which any pet owner can verify. Yes – pets are objects, but they are also articulate subjects; compliant enough and yet quite adept at getting what they want.

And I’m not just talking about belly rubs here. The hunting relationship that emerged between early man and certain wolves, fundamentally changed the fortunes of both and caused far-reaching consequences for entire ecosystems. There is considerable evidence that this brutally efficient partnership pushed our cousins the Neanderthals, who were reliant on the same food supply, toward extinction, as well as wiping out such iconic megafauna as woolly rhinoceros, mammoths and giant bison. These big, dangerous beasts could be tracked down and held at bay by the wolves-becoming-dogs, until Homo sapiens could catch up with them, wielding spears and arrows lobbed from a safe distance, reducing the risk of themselves being killed or injured in the hunt. These early human-imprinted wolf lineages gradually morphed into the manifold forms that are the domestic dog today – everything from teacup Chihuahuas to French bulldogs to Great Danes; the beloved beneficiaries of canned food, over-priced veterinary care and doting human companions who reverentially follow them around wrapping their hot faeces up in plastic bags.

Amazingly, one of the key factors facilitating the success of our co-mingling seems to have been the whites, the sclera of our eyes; an unusual trait in animals shared by both man and dog, which enabled us to quickly and noiselessly perceive what the other was looking at – ‘I am seeing–you are seeing me–seeing’ – an immense advantage in the fast-moving context of the hunt.

Our relationship with dogs has stood the test of time, despite our frequent cruelty towards them; the beatings, pitting them against each other in fights, sometimes even eating them.

So it might seem as if dogs were incapable of holding a grudge – but what if they finally had enough? The recent Hungarian film ‘White God,’ imagines a scenario in which abused dogs band together to take over the streets of Budapest in a mass revolt against their human tormentors. What results is a cinematic love child of ‘Lassie Come Home’ and ‘Battleship Potemkin’. More than any film I’ve seen lately, ‘White God,’ portrays the world from the animals point of view. The schlocky 1971 ‘rat-sploitation’ film, ‘Willard’ broaches similar territory, (if I am not misremembering it too egregiously) but nowhere nearly as adroitly. In both films, the human protagonists, while sympathetic, are basically just catalysts for the unleashing of raw animal rage.

Yet dogs, revolutionary or otherwise, do share with us a mammalian physiology which we can closely relate to.

But what of the creatures we choose to live with that are less like us? How might we imagine their Umwelt?

Birds have long been popular pets and some of them, notably parrots, can perform what to us seem like prodigious feats of intelligence. The famous African grey, Alex, was not only conversant in English but used it in a way that showed a grasp of syntax and numbers. Though they don’t all use our vocabulary, other birds like the Chestnut Babbler also use syntax in their communications, using different word combinations to convey different concepts: nest, food, sky etc. Though they use language, birds are physiologically much more distant from us than are dogs, having much more in common with the therapod dinosaurs they descended from than with any of us upstart mammals.

What must it be like to experience the world through a super light weight, hollow-boned body, capable at any point of launching itself into the air, every breath sucked in by a hyper-efficient respiratory system that can power marathon, trans-hemispheric flights through the vastness of the sky, with minimal food or rest? And they start their lives by pecking their way out of a hard-shelled, externally incubated egg!

Clearly, bird subjectivity is not our subjectivity and yet we may figure in their Umwelten, especially if we have established some kind of a relationship with them, as the people who keep them, the people who enjoy feeding them in their yards, the people who obsessively watch them, recording their sightings on lists.

Birds though, are usually most interested in other birds, their predators and prey, as well as the complex topology of trajectories and territorial designations that signify their habitat.

Even that is somewhat of a generalization, for it is what Von Uexküll calls receptor images that turn out to be the major drivers for bird behaviour. He describes certain jackdaw (a small crow-like bird) that would attack any cat or human experimenter carrying a dead jackdaw. When the experimenter showed up with a limp pair of black bathing trunks in his hands, the jackdaw similarly goes on the offensive. Yet it didn’t bat an avian eye when a dead white jackdaw (presumably an albino) was paraded by it. It was the blackness combined with limpness that seemed to trigger this specific bird – not the ‘bird-ness’ of what he was seeing.

By cultivating a practice of not anthropomorphizing, but trying instead to grasp the semiotic universes in which animals exist; what they think is important; we can develop a much more nuanced appreciation for those with whom we share the planet. Their worlds are not our worlds, but sometimes they overlap!

Says Von Uexküll:

We are easily deluded into assuming that the relationship between a foreign subject and the objects in his world exists on the same spatial and temporal plane as our own relations with the objects in our human world. This fallacy is fed by the belief in the existence of a single world, into which all living creatures are pigeon-holed. This gives rise to the widespread conviction that there is only one space and time for all living things…There is no space independent of subjects. If we cling to the fiction of an all-encompassing universal space, we do so only because this conventional fable facilitates mutual communication.

So perceptions of time as well as space are key elements of a given Umwelt.

Looking back down at Marmaduke, staring up at me from the floor makes me wonder how our relationships to time differ. There are for me, the obvious physical markers. In the nearly five decades we’ve lived together, I have progressed from boyhood to adulthood, to middle age, with all its attendant physical complications and catastrophes. For his part, Marmaduke seems nearly indistinguishable from his dapper, youthful self, save for a slight fading of his orange neck pigmentation and the unfortunate cross-bite he acquired after breaking his beak some years ago, when he fell off a pile of books he was climbing.

Does time move slower for him – or faster?

Again Von Uexküll offers us insight, reminding us that time is the product of a subject:

Time as a succession of moments varies from one Umwelt to another according to the number of moments experienced by different subjects within the same span of time. A moment is the smallest indivisible time vessel, for it is the expression of an indivisible elementary sensation, the so called moment-sign…

The question arises whether there are animals whose sense of perceptual time consists of shorter or longer moments than ours, and in whose Umwelt motor processes are consequently enacted more slowly or more quickly than in ours.

Which is fascinating…

In his novel ‘The Possibility of an Island,’ Michel Houllebecq imagines the bittersweet feelings of an immortal protagonist living in the near future, toward his little dog ‘Fox’, which is not ‘a’ little dog per se, but many little dogs, or rather a never-ending succession of the same dog – cloned: each replaced by its own puppy self as soon it has lived out its normal, dog-appropriate life span.

The variance in perceptual time between dog and master invokes some sombre reflection on the part of the post-human Daniel, who otherwise experiences the ebbs and flows of the post apocalyptic world outside his gated compound with an almost geologic detachment. Years pass, and not much consequential happens, except his dogs dying every once in a while to remind him of the chronology of the natural world.

But what if we turn the tables and imagine ourselves in the mind of a creature that can outlive us?

Spare a thought for example for that bowhead whale killed off the coast of Alaska in 2007. It had a harpoon tip lodged in its neck blubber dating back to the 1890’s. This venerable but unfortunate leviathan, possibly over 150 years old, spent more than a century dodging a repeat encounter with our murderous species, out-lasting the end of the commercial whaling industry, only to wind up dead in a relictual aboriginal hunt. Had it become world-weary, plying the plastic-strewn, anthropogenically warmed polar sea and thinking:

‘To hell with it! I’m exhausted… Maybe I’ll just end it all and offer myself up to these Inuit. They seem like nice people…’

Or maybe it just got unlucky.

Then there are the tortoises – venerable, patient as boulders…

Tu’Malila, a Madagascar radiated tortoise lived with successive generations of the Tongan royal family from 1779 until 1965, after having been brought there by the peripatetic Captain Cook. Jonathan, a giant Seychelles tortoise is still alive at 182 years, exiled like Napoleon, to the distant south Atlantic island of St. Helena. What do these ancients think of us as they observe, through rheumy reptilian eyes, our frenetic comings and goings? We must seem like crazed, bipedal ants, our over-clocked, distractible brains constantly driving us to keep doing things, while they blink and wheeze and munch placidly on soft weeds, noticing perhaps the shift in the angle of the sun as the season progresses or the promise of rain in the great vault of weather boiling high overhead.

Compared to these Methuselahs, Marmaduke is but a spring chicken yet I can’t help wondering how, over our past half century of cohabitation, he thinks about the time passing – or if in fact he even thinks about it! His routine has been remarkably constant: he enjoys basking in the patch of sun that conjures itself up beneath the office skylight at a certain hour in the morning. He tucks into his miniature portion of organic dog food and lettuce leaves with apparent gusto, if the ambient temperature is high enough. There are also his long soaks in his water dish to relieve constipation. That might be fun!

But mostly he just sleeps in one of his several favourite hiding places under my bookshelves. When the house cools down in the winter, these naps can go on for weeks. Being able to remain inactive for long periods confers tangible benefits to turtles, helping them avoid predators, endure inclement weather and interruptions to the food supply. Perhaps these super naps have cognitive benefits too – a pause from too much stimulation, a time to process all they have taken in. Perhaps they meditate Who knows? Perhaps these naps are the way box turtles mark time…

Though his sense of time is opaque to me, I can see that the locations of objects within his operational space seem to matter a great deal. Marmaduke promptly investigates the appearances and disappearances of my knapsack on the floor or any new pile of books or magazines that get put there. Maybe this is evidence of some sort of spatial prioritization, an Umwelt consisting primarily of assemblages of obstacles and hiding places he must negotiate in order to move about efficiently and unobtrusively. Time may have no meaning in such a world, other than the cycles of light and darkness by which objects are illuminated.

As a narcissistic human, I am particularly curious if after all these years Marmaduke has developed any emotional attachment toward me. I’m resigned to the fact that it’s not likely I’ll ever find out. Affection, in the way we humans might understand it, is not something reptiles tend to exhibit, despite this turtle’s entreating use of eye contact when wants to be fed. There is no way of telling what my face even means in his reptilian Umwelt, merely that he has learned that if he stares at it long enough, I will eventually notice him and take care of his needs. In the Venn diagram of our lives, these moments of turtle-initiated communication are where we most overlap. At least it’s something…

Cousteau in a pensive moment In contrast to their slow-pokey terrestrial cousins, water turtles can seem quick-witted and engaging. Of the freshwater species, the softshell turtles and the similar pig-nosed turtles are the most thoroughly aquatic, gliding through their watery realm with an almost balletic grace. Though I’ve only admired pig-nosed turtles with my face pressed up against the glass of the Berlin Aquarium, I have been living with a pair of soft-shelled turtles, since 1997, having raised them from tiny hatchlings.

Pig-nosed turtle at Berlin Aquarium To say these creatures are odd is a supreme understatement. Their flexible shells are the texture of wet baseball gloves and they have curious, tube-like snouts, which they employ like snorkels. Temperamentally, softshells are highly idiosyncratic and thus require a fair amount of sensitivity and attention on the part of their keeper, which makes them, it needs to be said, terrible pets, for anyone not willing to devote massive amounts of time to understanding their subtle emotional cues, let alone their physical needs for commodious aquaria with fastidiously filtered, expensively heated water and a carefully chosen substrate in which they will bury themselves for hours at a time, switching over to anal breathing so they don’t have to come up for air.

Cousteau, a female and by far the larger of the two, is a Florida softshell (Apalonia ferox) and neurotic in the extreme. The last time I weighed her, she came in at over 16 pounds and that was some years ago, so the two hundred gallon plexiglass tank of swamp water she inhabits no longer seems as excessive as it once did. Though she could easily amputate a finger with a snap of her wire cutter like jaws, Cousteau is painfully shy and goes into deep conniptions at the slightest departure from her accustomed routine: an unexpected noise, perhaps the clunk of a drinking glass on the coffee table, someone entering or leaving the room too abruptly, or even a play of light on the wall she may suddenly find disturbing. Thus agitated, she will bolt to the far corner of her tank with the back of her shell facing the room to sulk for possibly days before deigning to engage in the world again. She is similarly particular around her meal times, preferring her food pellets to be offered late at night, after midnight ideally, once the overhead lights are dimmed, the television tuned to BBC World News at an appropriately modest volume. And yes, I realize this is weird!

I came to discover these predilections through an arduous process of trial and error. On a couple of occasions, Cousteau put herself on a multi-month hunger strike when the conditions of her confinement were not quite to her liking, coming dangerously close to starving herself. Extreme, suicidal behaviour perhaps, but how else could she get my attention? Despite my having obsessively pored over all the literature I could get my hands on pertaining to softshell turtle biology, Cousteau was not just any softshell turtle, but an individual, steeped in her own enigmatic subjectivity. I had to put myself inside her Umwelt, to see things from her point of view – from the watery vantage point of her big aquarium in the corner of the living room.

Okay, I didn’t exactly climb into the tank with her, but started observing much more closely how she reacted to slight shifts in her living conditions – one variable at a time: the temperature of her water, at what time I was offering her food, the lighting, the ambient level of noise, the sonorousness and timbre of the way I spoke to her, and so on – until she slowly emerged from her deep funk. I live with a very large softshell turtle who prefers to eat late at night, with the television on and I need to talk softly to her while droppoing herring flavoured pellets in front of her tube-like nose. And I’m okay with that.

You know what it is to be born alone,

Baby tortoise!

The first day to heave your feet little by little

from the shell,

Not yet awake,

And remain lapsed on earth,

Not quite alive.

A tiny, fragile, half-animate bean.

To open your tiny beak-mouth, that looks as if

it would never open,

Like some iron door;

To lift the upper hawk-beak from the lower base

And reach your skinny little neck

And take your first bite at some dim bit of

herbage,

Alone, small insect,

Tiny bright-eye,

Slow one.

To take your first solitary bite

And move on your slow, solitary hunt.

Your bright, dark little eye,

Your eye of a dark disturbed night,

Under its slow lid, tiny baby tortoise,

So indomitable.

DH Lawrence: Becoming tortoise.

‘Baby’, a male spiny softshell turtle, inhabits a slightly smaller tank adjacent to the dining room. He is the polar opposite of Cousteau in almost all respects and the closest thing I have ever seen to a ’social’ reptile; constantly solicitous of human attention – a regular life-of-the-party, especially if people are gathered around the dinner table. If he isn’t asleep or hidden under the gravel breathing through his anus, Baby spends his time furiously gesticulating towards the nearest human, his webbed feet performing a kind of frantic semaphore, neck fully extended : Feed me! Feed me! Notice me! Notice me! in the hopes he’ll be tossed a food stick or just hung out with, which he very much seems to enjoy. But why? Obviously he likes being fed, but there seems to be more to it; a kind of intrinsic exuberance that Baby has always had even as a hatchling, no bigger than a quarter. Both Cousteau and Baby came into my life at around about the same time; tiny turtlets only days old; a so-called ‘by-catch’ in a shipment of farm-raised tropical fish. Neither would have experienced much beyond the cosseted interior of the eggs they had so recently slipped out of, maybe bobbing haplessly around in the fish pond for a few days before being scooped up, stuffed into an oxygen injected plastic bag and shipped to an airport. Yet right from the beginning, Cousteau and Baby were utterly different in the way they related to their respective worlds. Far from being ‘simple’ creatures they are –as we all are – individuals.

But must we live isolated within our unbridgeable solitudes? Is our access to animal subjectivity such an existential impossibility or limited to the realm of arcane thought experiment? Perhaps they can really enter our minds and we theirs? Maybe the boundaries between our Umwelten are more permeable, our becoming-animal within reach; dangling like the fibres Deleuze and Guattari envisioned in A Thousand Plateaus, as already connecting us in an enmeshed co-presence.

Perhaps it is a matter of memory. Maybe if we try to remember our animal dreams; the ones that remind us of what it is like to be them, we might be able to become them, at least once in a while.

The philosopher Paulo Virno declares dejà vu a memory of the present. How often have we looked at an animal and felt a deep connection, an overwhelming co-presence in which we briefly are: that cat purring, nestled by the warm hearth, the puppy gambolling in the soft spring grass, the butterfly unfurling its wings, the giant tortoise stoically observing the passage of the centuries through teary, brown eyes, now pausing to nip the petals off a flower?

Animals. We are them. They are us. That is why we like to hang out with them. That is why we should love them even more.

Like a titmouse, which a breeze gently rocks at the end of a sunbeam.

Proust: Remembrance of Things Past

So I was walking westward along East 10th St. early in the afternoon, feeling a little jet-lagged, having just got back to NYC after a month’s stay in Berlin. Moments before I’d said goodbye to Ruth as she boarded the M8 bus on her way to the West Village.

My first day back in a place I’ve been away from for a while can feel fresh and full of possibility, though I noticed that winter had been very slow to release its grip on old NYC this year and the sky was still grey, the trees unpromisingly bare and the sparrows disheveled as they pecked at a pizza crust along the sidewalk. A sudden rumble percussed the air – disconcerting louder than the usual construction noise, the ground shaking. My iPhone buzzed with an incoming text:

Ruth: “Did you hear that?”

Oliver: “Yes I did.”

She calls and tells me the people getting on her bus are talking about some kind of explosion.

“It’s probably nothing,” I said, (as if I knew what I was talking about)

But New York is an incredibly noisy place and one gets used to the din of sirens, pile drivings, and demolition noise that punctuates the background infrasound of thrumming traffic, the vibration of subways and the whoosh of steam conveyed through pipes hidden under the street.

So that was that, I thought and ducked into the barber shop I always go to 2nd Ave, to get a hair cut. It wasn’t busy and I hardly have any hair so it took only a few minutes to restore my stubble and by the time I got out, I could see grey smoke billowing up a short distance down the avenue, just south of the venerable Gem Spa news stand. A crowd had gathered and the first emergency vehicles were rolling in.

There is something horribly magnetic about a fire and I found myself heading toward it without even really thinking; though it was, broadly speaking, on my way home.

The intensity and volume of the smoke was getting worse by the minute and by the time I was a block closer, the fire department had deployed its high ladders and were blasting water from above onto the five story tenement, which by now was almost completely engulfed with the fire spreading to the adjacent. From that point on things moved very quickly, and in a few minutes we were being herded backward from the existing police cordon, at which point the intitial building blew up. It was surreal, horrible and one felt completely helpless knowing that what was happening, what one was seeing at that moment likely involved the loss of life – how could it not? Some of the onlookers were already sobbing or frantically calling or texting loved ones they thought might be in the vicinity and were not yet accounted for.

I exchanged a few words with the long time East Village character, Jim Power, a.k.a. the ‘Mosaic Man’, who had been darting in and out of the chaos on his motorized mobility scooter, sharing bits of news with onlookers and comforting the more obviously stricken. But what does one say in such a situation, other than to communicate one’s concern for the victims, the shock that such a thing has indeed happened; that this unremarkable building, with its sushi place, people’s apartments, their stuff, their lives, a building like so many others, a place that one might have even taken for granted, a mere blip in the optical subconscious–unless of course one lived there, knew people there–had so abruptly been ripped from our midst?

I worked my way eastward, away from the fire scene, looking back at the roiling column of smoke that by now must have visible throughout Lower Manhattan. Everywhere I looked, people had stopped in their tracks. Even five blocks away, knots of people gathered on the street corners, pointing at the sky and shaking their heads; all of us one moment in the midst of our quotidian routines and then presented with the sudden spectacle of disaster. That night the media confirmed what many on the street had been speculating – that the explosion, which cost two lives and injured 22 people was due to illegal modifications to the gas lines in the building. A couple of weeks later I happened to speak with one of the ConEd workers first on the scene and he lamented the criminally shoddy gas-fitting and shared how furious and frightened he was at the many cases of dangerously careless workmanship he so often encounters in his job, and how this continues to put all New Yorkers at grave risk.

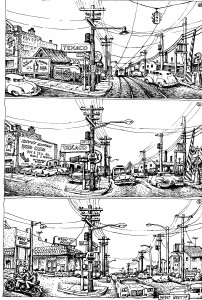

During the weeks that followed, as the ruins got pored over by teams of investigators and then proceeded to be gradually demolished, the intersection of 2nd Ave and 7th Street had the air of a grizzly carnival with satellite news trucks jammed into every available niche, television journalists recording their live spots against the backdrop of straining heavy machinery, mounds of simmering rubble and disaster tourists, posing for selfies – the tragic obliteration of half a city block endlessly mirrored in a mis en abyme of Instagram and Twitter updates; its cause, not terrorism as had been feared, but carelessness and callous indifference. And so Manhattan is left with yet another hole, a lacuna, which the forces of turbo-capitalism will soon fill. But with what?

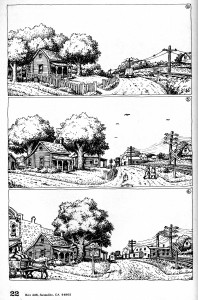

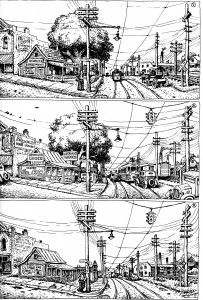

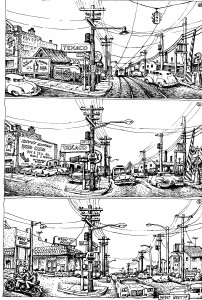

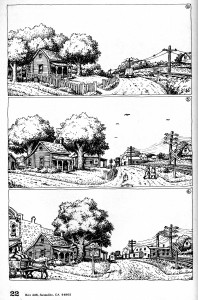

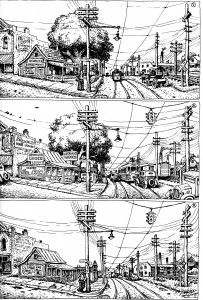

Even without such tragedies, the streetscape of the East Village is changing so rapidly I am almost always in a state of cognitive dissonance, looking for familiar landmarks that have disappeared, seemingly overnight, subsumed by the juggernaut of gentrification. These are ‘micro-worlds’ complete with endemic communities, ways of being, and so many of them are being lost: the affordable mom-and-pop eateries, the Hispanic botanicas, the dive bars, the squats, the bait stores along Houston – even the cars parked on the streets belie a degree of conspicuous wealth that would have been unthinkable but a decade ago. Though still a diverse and vibrant place, the neighbourhood has lost much of its character, its eccentricity, and has morphed into a theme park of its former rough-hewn self. The blogger Jeremiah Moss tracks this steady diminishment in “Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York”, which reads as a chronicle of cultural extinction. But Moss hasn’t given up and is at the vanguard of a resistance movement he calls ‘Save New York’ and he recently instigated a ‘Small Biz Crawl’ to help out vulnerable East Village businesses affected by the fire. But is authenticity, so reified, still authentic, or are have we fallen victim to some idealized nostalgia? The East Village at the dawn of punk rock was a much grittier, more menacing place with ubiquitous crime along with the cheap rents and opportunities for squatting. But it was this set of conditions that allowed a vibrant non-commercial culture to thrive, the fumes of which the East Village is still running on to this day. At some point though, this will be forgotten.

When small establishments close down and are replaced by banks and chain stores, a sense of ‘placelessness’ descends. The likes of Subway, Starbucks and Urban Outfitters are essentially machines, ‘non-places,’ as the critic Marc Augé puts it, interchangeable with others anywhere in the world provided they share the brand. The human interactions occurring within–optimized, efficient and perhaps even affordable, are insipid, anonymous and non-relational and I would argue, contributory to the epidemic of loneliness we are now facing. A sense of allegiance, a feeling of belonging to the local, a culture of identifiable place, is lost when that place becomes just another instantiation of a globalized retail platform. When our every public interaction is imbued with overarching commerciality, we have a recipe for psychological disaster.

In her Guardian essay: ‘The Future of Loneliness,’ Olivia Laing makes the case that the internet, in particular social media, is the ultimate commercialized non-place, where the made-up-ness of one’s on-line persona commodifies personal relationships into ‘likes’ and ‘re-tweets,’ distancing the messiness, the imperfection of the real; resulting, says Laing: “ in being looked at and not seen.” We engage with each other in a state of ‘hyper-anxiety’ – constantly surveilled yet never understood.

Laing goes on to reference the quite excellent ‘Surround Audience’ exhibition now on at the New Museum, which for her epitomizes this anomic, yet narcissistic aesthetic. When I visited the show, the work most literally embodying the sense of pervasive social isolation for me was the series of quarantine chambers designed by the Chinese artist Nadim Abbas, entitled: Chamber 664, 665 and 666, each containing an abject sleeping bunk and some personal effects that can only be contacted through a pair of thick rubber gloves – a metaphor it seems to me, as apt for ebola as it is for Facebook.

That this epidemic of loneliness, this feeling of ‘not being seen’, might have consequences far beyond individual indisposition is what the Marxist critic, Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, suggests in his provocative reflections – ‘In the lonely cockpit of our lives’ on the recent Germanwings crash, by now widely believed to have been an intentional act by its co-pilot, Andreas Lubitz. For Berardi, neo-liberal capitalism, with its relentless competition and ubiquitous connectivity, is responsible for us running into the ‘embrace of the black dog’ – the system’s demands have transformed our social lives into ‘a factory of unhappiness of which it appears impossible to escape.’

He goes on to declare:

“(Lubitz) did what he did because he could not get rid of the unhappiness that has been devouring contemporary mankind since advertising began bombing the social brain with mandatory cheerfulness, and digital loneliness has been multiplying the nervous stimulation and encasing the bodies in the cage of the screen, and financial capitalism has been forcing everybody to work more and more time for the miserable salary of precariousness.”

A more extreme form of Berardi’s proposition was foreshadowed, in part violently, in the early 1970’s, by the radical German therapist, Dr. Wolfgang Huber and his Socialist Patient’s Collective, who believed that psychiatric disorders stemmed from the capitalist system and could only be cured by a turn to a Marxist society. Though the therapeutic aspects of Marxism as it has thus far been applied can most charitably be described as ‘mixed,’ the psychological stress engendered as contemporary neo-liberalism subsumes all aspects of our lives into a pervasive, competitive commerciality need to be taken much more seriously. The system’s increasing inhumanity, its emptiness, is clearly driving people crazy yet rarely do we critique its basic legitimacy. Horrific events like the Germanwings crash may well be the symptom, not the disease.

via National Geographic The overwhelming sensation of diminishment in our working lives and in our relationships with each other is compounded in turn by the vertiginously decreasing finitude of the natural world on which our human institutions, our very lives, depend. We are bombarded with heartbreaking images of ending –the last male western white rhinoceros left in the world, with his abbreviated yet still too valuable nub of a horn, encircled in his placid grazing by a full-time phalanx of armed guards, there to protect him from poachers. We’ve reached the point where there is not a single territory on this planet where such a lonely and iconic creature could live out its life outside the market system. So it is doomed to die.

That we are in the midst of an anthropogenic ’Six Extinction’ event is well known and the artist Brandon Ballengée (who I was in a show with at the Media Sanctuary in Troy New York last spring) recently produced a series of works called ‘Frameworks of Absence’ in which he represented the lacunae of extinction quite literally, by cutting the images of extinct creatures out of historical prints and burning them, leaving behind ghostly white absences amid backgrounds depicting their idealized habitats.

With or without extinction, climate change will create absences in what we have once held familiar. Researchers have recently estimated the velocity of climate change in temperate zones to be approximately a meter a day, poleward or upward; meaning that in a given nature reserve, the localities having now the coldest conditions will be hotter than the places that are now the warmest, within a hundred or so years – the mountaintops becoming as hot as the deserts they loom over are now, and so on. This means species requiring specific temperature ranges will have to migrate higher in latitude or altitude to survive, provided there are no barriers to movement, which in the real world is often not the case. Alpine and polar organisms will be particularly vulnerable, as they often already inhabit the extremes of what is topographically possible and will likely run out of accessible places to move – ‘deterritorialized’ literally, into oblivion.

Other species, now at home in more southerly regions, will need to move northward, as their accustomed haunts become uncomfortably hot. In places such as the North American west coast such migration would be impeded by almost insurmountable man-made obstacles in the form of massive cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles, which interrupt the continuum, the cline, of available habitat.

In such cases we might initiate preemptive, ‘assisted’ migrations, which I have investigated over the past years in my ‘Neo-Eocene’ project – a logged-over acreage in coastal British Columbia, where I have planted hundreds of young coast redwood, giant sequoia, walnut and gingko trees, all native to more southerly zones, in anticipation that continuing warming trends will create conditions more favourable to them, and less favourable to the vegetation now considered to be native. So far so good, with the coast redwoods making the most impressive progress, thriving unassisted, almost 1000 kilometres north of their closest native range. The sequoias too are making considerable gains, which is reassuring given the prognosis for their survival in their Sierra Nevada home is increasingly grim, to the extent that by some estimates natural sequoia groves are unlikely to make it through the area’s shift toward permanent drought without artificial irrigation and the construction of fire breaks. Is there not a certain poignancy to the fact that we might only manage to preserve something of the primeval sublime of the sequoia groves through the epic administration of artificiality? But then the climate itself has become a human artifact. We broke it we fix it, I guess, only we can’t fix it, not really, not any more. But absence makes the heart grow fonder. Which makes the Anthropocene the biggest lacuna of them all.

George? Who were you George?

I’m standing beside a plexiglass vitrine at the American Museum of Natural History. In it are the taxidermied remains of George, the last Pinta Island Galapagos tortoise, who died suddenly on June 24th 2012, of so called ‘natural causes.’ At the time of his death, George was estimated to be about 100 years old – a spring chicken by tortoise standards, and sadly he passed away without carrying on his illustrious line. All other members of his Chelonoidis nigra abingdoni subspecies predeceased him, their once considerable numbers decimated by passing sailors who hunted them down as easy to catch and easy to store meat that could be kept alive in the holds of their ships for months. The few Pinta tortoises the sailors missed mostly starved to death after goats got introduced to Pinta in 1959, which then stripped away the vegetation they needed for food and cover. How George survived alone, until he was discovered when he came out of hiding in 1971, is still a bit of a mystery but he was soon shipped off to the Charles Darwin Research Station on nearby Santa Cruz in the hopes he might mate with females of a related subspecies and perhaps sire hybrid offspring to make situation of his genetic extinguishment a little less final. But it was not to be and George during the years of his confinement remained something of a sad curiosity, the embodiment of a ‘zombie species,’ still scrabbling around but already functionally extinct.

When George died in his enclosure, his head pointing poignantly in the direction of his drinking pool, his remains were promptly frozen and shipped off to the AMNH where he was set upon by a crack team of embalmers, who (it has to be said) did an amazing job making them look almost perky. The AMNH produced an informative video documenting the taxidermist’s macabre prestidigitations; the agonizing decision making of choosing the appropriate pose, getting the correct drape of his wrinkly skin right, the touchings up with paints and varnishes, the fastidious attention to detail neccessitating even splotches of authentic Galapagos dust to be daubed onto George’s eviscerated carapace.

Lenin In his temporary mausoleum in the museum’s Astor Turret, George draws quite a crowd and he rather gives the impression of a reptilian Lenin, serene beneath the glass of his tomb, while crowds of supplicants stream by to pay their respects or merely snap a selfie or two while standing next to what was after all ‘the last of his kind.’ Other than a striking similarity in head shape, both lonesome George and Vladimir Ilyich shared the quality of becoming even more iconic after death, more laden with gravitas, their formaldehyde and wax-infused corpses the recipients of both veneration and revisionist history – George the last survivor of an imagined, prelapsarian, South Sea eden; Lenin the last ‘authentic’ Bolshevik.

The preservation of corpses, whether through taxidermy, embalming, or ritual mummification, seeks to reframe the life of the deceased into an idealized, one could say fetishized state; the gory circumstances of the death, the bleeding bullet holes torn through the flanks of the game animal before its final agonized collapse, the sunken flesh of the terminally ill patient after a long confinement, all cleverly obscured to make them look as they were in life, or rather, as they should have been according to the aesthetic agendas of their posthumous manipulators. Whether it be a valued hunting trophy or the body of a notable lying in state, what we are dealing with here is the grammar of propaganda and we should see it for what it is.

Lenin for instance appears as if he is rather beatifically following the whispers of his visitors from just under the lightest of naps, a fatherly figure enjoying a well-earned rest after finally putting things right with the world. Our tortoise George is displayed with an eagerly outstretched neck and custom-made eyes, beady and enthusiastic, as if he were about to embark on some pleasant chelonian journey, to a parallel universe perhaps where females of his kind still exist and the unpleasant finality of his extinction no longer needs to be contemplated. Though I won’t get into specifics of Lenin’s multifarious legacy, I’m not going out on a limb to say he’d have more than a little to account for if he ever woke up from that satin lined coffin of his. As for George, his carefully posed death puppet of a body has been spun by the AMNH and the Galapagos Conservancy, not as a symbol of our abject failure to preserve threatened fauna (which by some estimates we are losing at a rate of 140,000 species per year) but as an icon of high-minded wild life conservationism.

While I am all for a ‘glass half full’ outlook (and there have been some encouraging recent gains regarding Galapagos tortoise breeding), the AMNH’s attempt to transform poor dead George into a crowd-pleasing, feel good, story is one symptom of the museum’s larger initiative to revise their kill em’ and stuff em’ legacy into something more palatable to the contemporary metropolitan audience. It is of course laudable that the museum is now a ‘force for the good’ and active in world-wide efforts at conservation; a leader in the research of global biodiversity, but by papering over its extensive and enthusiastic record of ’collecting,’ that is to say, killing of scores of rare animals to create its famous, crowd-pleasing displays, we are deprived of an opportunity to learn from the institution’s history and to celebrate how far attitudes have generally come.

Let us look at the history of one of the AMNH’s iconic assets, the Akeley Hall of African Animals, a veritable temple of dioramas, each representing a major ecosystems of the continent. The centrepiece is an entire herd of elephants, massacred specifically for the display and arranged on a plinth what is described as an ‘alarm formation.’ Among them are a mother and calf shot by none other than Theodore Roosevelt and his son Kermit, who were actually over in Africa shooting elephants for AMNH’s rival, the Smithsonian but they generously bagged a couple of extra for their friends in New York, who after all needed a lot of them for their imposing composition and anyway, one gets the impression they were kind of on a roll. Even by the standards of the early 20th century, there would have been little scientific justification for this carnage and the herd of elephants frozen in mid outrage had a lot more to do with creating a spectacle than advancing any frontiers of zoological knowledge. These days we might more rightly regard this abomination as a reminder of the cruelty, barbarism and entitlement of the self-styled Great White Hunters of times gone by, a regrettable monument to what happens when colonialist privilege meets excess testosterone. And yet the AMNH makes no obvious effort to explicate or contextualize any of this. Their messaging to museum-going children is still that: ‘dead elephants are cool!’

The bulk of the hall is taken up by the dioramas proper, exquisitely painted tromp-l’oeil backdrops of arid, acacia studded plains and seething, hyper-vegetated rain forests in front of which naturalistic groupings of dead animals have been placed – rhinos wallowing in mud, apes clinging to jungly vines with adorable infants suckling at their breasts, antelopes of all shapes and sizes, big cats, giraffes, and just about any other creature one might expect to be found prowling, galloping or climbing through the idealized environs of a primeval Africa.

What the museum consciously underplays here is that these beguiling displays celebrate not only Africa’s once manifold biodiversity, but an entirely different aesthetic–a competitive materialism on the part of First World collectors, who in their fetishization of the exotic, spent considerable sums tracking down and killing some of the rarest, most elusive creatures on the planet to bring back as publicly exhibited trophies (let’s call them what they are) and to not so subtly underscore the power relationship between American empire and what was even then an increasingly subjugated global ’wild,’ a disappearing frontier of primeval ecosystems in the midst of colonialist exploitation. The dioramas, with their illusion of intimacy exist within the dissonance of us thinking that somewhere out there is still the possibility of an Eden while at the same time knowing that what is in front of us is an arrangement of dead skins propped up on armatures of wood wool and mothballs.

The not so subtle message of the AMNH’s dioramas is:

’ Nothing is beyond the reach of our guns,’

(or perhaps:)

‘To the victor – the spoils!’

Sumatran Rhinos By the time the museum’s Hall of Asian Animals was being set up by Colonel John Faunthorpe and Arthur Vernay, a wealthy, British-born, New York antiques dealer, some animals such as the Sumatran rhinoceros and Asiatic lion were already going extinct in their native habitats and much was made of the lengths Vernay had to go through, the many appeals and entreaties he had to make to get the hunting permits needed to kill still more of them for his displays.

Was it all for a good cause, this science-minded collecting of critically endangered animals such as the mother Sumatran rhinoceros, shot along with her little calf for the edification of Gotham’s discerning, museum-going public? From a present day perspective, their dark little diorama seems particularly sad, a testament to a completionist obsession, the acquisition of rhinoceroses as if they were hockey cards or Royal Doulton figurines, regardless of the precariousness of the animals’ status in the wild; in fact spurred on by their tantalizing scarcity.

There is no doubt that in the past the demand from museums seeking rarities hastened the extinction of more than a few species and it would be helpful for our understanding of changing attitudes if the AMNH would take it upon themselves to highlight this dark side of their collection building. To be fair, this acquisitiveness was the norm for most natural history museums of the 19th and early 20th centuries, in both the public and private spheres. They weren’t always the bastions of wildlife conservation they now promote themselves as. While valuable taxonomic understanding can indeed be gleaned from specimens killed in the field, the slaughter of whole herds of elephants and entire rookeries of seabirds – even the nestlings peeled from their delicate skins to be stuffed and varnished– could never have been justified as ‘science’ even by the standards of the day. These are circus sideshows we should rightly view them as archaic, even vulgar. Though the Halls of African and Asian animals can perhaps be reconsidered as historic monuments to the quaint but also cruel attitudes of a bygone age, the museum’s media hoopla around their taxidermification of poor, dead George, seems anachronistic to say the least. We learn very little from a dead Galapagos tortoise, no matter how cleverly he is mounted. George now exists as an art-directed ‘thing,’ optimized to look the way we expect him to and no longer a ‘being,’ with his own agency and life world. We screwed up and he went extinct. No amount of paint and fibreglass will change that tragic fact.

North Troy NY brownfield savanna

safari into the Williamette Cove brownfields

Those of who call ourselves ‘environmentalists’ have a tendency to imagine a prelapsarian wilderness that once was pristine and then became progressively defiled and diminished through the carelessness of humankind. But the earth had been through many environmental catastrophes long before we came along– though this doesn’t exactly excuse us from our manifold sins. The infamous Chixculub asteroid impact suddenly ended the long reign of the dinosaurs and the more insidious yet equally catastrophic evolution of photosynthesis deep within the cells of certain cyanobacteria contaminated the earth’s early biosphere with oxygen– a fatal poison to the majority of organisms present at the time, resulting in what is now known as the oxygen catastrophe, a mass die-off of the earth’s biodiversity and a climate change event that froze the planet in the longest snowball earth episode in geologic history.

What is unique in the present (Anthropocenic) moment is that we know we are causing a massive and likely suicidal ecological crisis and yet choose not to do anything about it. Here we are at the tail end of 2014 with atmospheric CO2 levels higher than they’ve been for 800,000 years and the 6th mass extinction accelerating to the point where the earth has lost half of its wildlife species in the past 40 years. Political leaders, particularly those of oil rich countries like my native Canada either willfully ignore the scientific consensus or in the most egregious cases, (again Canada), actively censor the findings of scientists and even weather forecasters. Because a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing. Or is it?

In a recent video, Žižek makes the perhaps startling case that there is considerable poetry in our present situation, that is to say, our disavowal, our state of knowing that something is true and yet acting as if it wasn’t. He argues that to “truly love the world, we must love its imperfections,” including, presumably, the ones for which we are directly responsible. “In trash,” he declares “is the true love of the world,” a sentiment similarly observed by a Zen priest in the masterful little documentary, Tokyo Waka, which explores the world of Tokyo’s ubiquitous and trash loving crows. To be more precise the priest observes: “In trash is the residue of desire,” a sentiment perhaps less direct but still elevating garbage to a kind of reified affection.

To follow that logic, when an entire landscape becomes trashed, it should be particularly worthy of our love and it was in this spirit that I embarked upon my summer explorations…

But first some background: The Superfund was originally set up in the America in 1980 to identify and facilitate the cleaning up of the country’s most hazardous waste sites. In theory this might have created sufficient funding and legislative willpower to deal with this dangerous and unhealthy problem but between partisan politics and bureaucratic ineptitude, implementation fell far short of what was needed.

Though most people would want steer clear of toxic wastelands, I wanted to see if there were any adaptive ecological processes operating there that might be transforming these zones of exclusion into useable habitats. I had the strong sense that conventional ecologists and environmentalists might be missing something very important, that nature was capable of doing an end run around our destruction, if only we would get out of the way. My summer safari took me to sites on both sides of the continent–Troy, NY and Portland, Oregon–and what I observed there gave me some hope and insight into nature’s surprising ability to colonize the messes we have left behind.

I was invited to Troy by my pal Kathy High for a collaborative investigation into the area’s extensive brownfields. Once known as the ‘collar city’ for its shirt, collar and textile production, Troy is considered the birthplace (and graveyard?) of the American industrial revolution. A fortuitous confluence of rivers made it possible for early factories to harness abundant mechanical (and eventually hydroelectric) power as well as to cheaply transport products and raw materials. Like so much of America’s industrial heartland, the area has suffered from economic decline and many of its once thrumming factories lie in ruin in within highly contaminated terrain.

Some of the worst sites are situated along the banks of the picturesque Hudson River, which transitions here from tidal to freshwater, the end of a long estuary. Downstream, all of the Hudson is classed as a Superfund site because of extensive contamination by PCBs, a potent carcinogen, dumped for decades by the General Electric Corporation as a byproduct of manufacturing transformers and other electrical components. PCB’s are a persistent organic pollutant (POP) that bioaccumulate in the river’s fish, making many species unsafe to eat–including the reputedly delicious striped bass that spawns nearby at the junction of the Hudson and Mohawk rivers.

chimney swifts over North Troy Despite being a very degraded ecosystem Troy’s former industrial landsa are full of surprises. As part of a summer youth program, I led a ‘bio blitz’ of a community garden that had been established on a brownfield site near the Sanctuary for Independent Media. It wasn’t long before we found a magnificent stag beetle hiding in the rotting stump of an (invasive! exotic!) Ailanthus tree. High overhead, chimney swifts traced their invisible arabesques into the topaz air of the summer evening. This species, has long adapted to human presence and as indicated by its common name, makes its nests in disused chimneys. The chimney swift is a close relative of the Vaux’s swift, which puts up a spectacular display every evening as great clouds of the birds funnel into in a large chimney at the Chapman School in Portland, Oregon.

A local Troy resident told me she had recently found red-backed salamanders under debris in her backyard yard, situated quite near some of city’s most contaminated industrial sites, with nothing that might be deemed ‘intact’ woodland anywhere in the vicinity. With the sharp decline of amphibians worldwide, even in protected national parks, it might seem surprising to find them surviving in such anthropogenically disturbed habitats but this is consistent with findings in the UK where rare newts and other amphibians as well as lizards, slow-worms and grass snakes make their last stands in these unprepossessing environs, among the trash, eroding pavements and ruined buildings. In fact brownfields turn out to be far more suitable habitat for these delicate little creatures than is the intensively managed agricultural landscape that has obliterated large tracts of Europes’s biologically diverse ‘Kulturlandschaft’.

stag beetle in Ailanthus stump At a Superfund site at the foot of Troy’s Ingalls Ave, I watched turkey vultures soar over an edenic looking mosaic of meadowy expanses that have cloaked the heavily contaminated soil. These neo-savannahs are punctuated by lush groves–a botanical mosh pit of weedy natives like box elder, black locust and cottonwood mixed in with exotic Ailanthus and Paulownia. All of this is gloriously unmanaged, left to its own rampancy, and though the species constituting this habitat are largely considered ‘invasive,’ they embody a new kind of ecological becoming, their novel juxtapositionings and processes of succession–a ‘Nature 2.0′ in the making.

If we put aside our purist bias, we might celebrate brownfields as territories of regeneration and marvel at how they adapt to the disturbances and wastes we leave in our wake. One might even regard them as ‘wilderness’ of a certain kind as they are one of the few ecological realms we have let slip from our control–leaving them free to reconfigure themselves and follow independent trajectories of neo-evolution.

Troy NY’s future brownfield rangers The collapse of industry though, leaves more than just picturesque ruins and novel habitat in its wake. For human communities,‘Detroitization’ means decaying infrastructure, diminished economic opportunity and the adverse health effects of pervasive chemical contamination. If sufficiently de-toxified, these lands can be rehabilitated as perfectly reasonable urban nature parks (see my previous posting on Berlin’s Templehof airport) but the challenge is to do so without diminishing their often surprising biodiversity.

Troy might be an ideal location for a Brownfields National Park, where local youth could work as ‘brownfield rangers,’ leading tours of the area’s ecological and historical heritage as well as doing field studies and cataloging the species to be found there. Though this necessitates a change of perspective in what we North Americans typically think of as a ‘natural’ park experience, it is high time we open our minds to such opportunities. Brownfields are the future. Brownfields are us!

Over on the other side of the continent, I met up with artist Marina Zurkow in Portland, Oregon. Together, we led artistic incursions into a Superfund site on the edge of the Williamette River. We explored first by water, using a flotilla of kayaks peopled by an intrepid collection of individuals who responded to our call for participation in what (to the less adventurous) might have seemed an arcane enterprise. We conceived our expedition as a kind of group imagination exercise and christened it -“IF YOU SEE IT–BE IT!” in the spirit of the biosemiotician Jacob Von Uexküll, who did such groundbreaking research on the spatio-temporal worlds of animals, which he termed the ‘Umwelt.’ Aboard our tiny craft, we collectively tried to imagine/channel what it might have been like to navigate the contaminated and disturbed riparian environment from an animal’s point of view (water striders, otters, sturgeons, etc.) – inhabiting (in our mind’s eye) their biosemiotic state, ‘becoming’ them, as it were, in a collective thought exercise.

Marina’s long term plan is to construct a raft-like roving laboratory she calls the Floating Studio for Dark Ecology, on which artists and researchers ply the river, exploring its narratives of contamination and recovery as well as disseminating practices of contemplation and engagement between its human and non-human communities.

Our early evening voyage proved suitably anthropocenic: a bald eagle gliding through the shimmering cottonwoods of Ross Island–a section of river whose bed is being continually scoured by heavy gravel mining machinery–the blue tarp and scrap lumber bricolage of homeless encampments festooning the banks of the Williamette–the third world within the first world, the metabolic waste of neoliberal capitalism as it eats its way through our material reality.

Neo-ecologies of Williamette Cove Once again there were fascinating and new ecological assemblage in these zones of dereliction and abandonment. Washed up on the industrial shore of a former shipyard–exquisite hydrozoans of a type I have never seen before:

hydrozoan The brownfields of the former factory site at Williamette Cove, though dangerously contaminated with heavy metals, wood preservatives and organic pollutants, proved not so ‘brown’ after all and were resplendent with novel botanical groupings–neo-succession! Native species like Arbutus menziesii (Madrone) formed habitat groupings with such hardy exotics as Paulownia tomentosa (princess or empress Tree) and Crataegus monogyna (European hawthorn). It is thought the empress trees made their original landfall in North America via their fluffy seeds, once used as a packing material for porcelain and other fragile goods originating in China and Japan. A gust of wind and an open crate at the dockside and their botanical colonization of the continent would have been begun.

In addition to brownfield neo-ecologies there is a parallel and equally fascinating neo-geology emerging from the material detritus of our age. Mineralogically, these are mostly composites and conglomerates or pyrolized residues of industrial processes such as coke and slag, as well as ceramics that have been fired into the form of brick, tile and pipe, much of it broken up into rubble. This so-called ‘urbanite’ is dominated by concrete and ferro-cement in various states of decay and petrochemically based asphalt and asphalt concrete, widely used in paving.

Sometimes though, a geologic object occurs that is of more obscure though still clearly anthropogenic provenance. At Williamette Cove, we came upon an exquisite specimen–a fossil of sorts–consisting of a fused mass of ribbed metal fragments, the armouring of industrial electrical cable, set within a matrix of a more indeterminate material, which might have been partially incinerated plastic. Perhaps this mystery mineral was formed when some itinerant metal collector tried to salvage copper wire by throwing scrounged cable into a campfire to melt off its rubber insulation and loosen the metal cladding. I may never discover this exquisite object’s true origin and it might well become the topic of frenzied conjecture to some future archeologist, wondering what our experience was like as we drifted deeper into the fraught and turbulent horizon of our anthropocenic future.

neo-geological form

where it all went down… The great blue bowl of the California sky has doubtlessly presided over some strange affairs, but perhaps none is stranger than the serial cycle of entrapment and petrification that started around 38,000 years ago in a collection of deceptively limpid ponds in what is now a quiet park in downtown Los Angeles. After it rains here, the play of sunlight and clouds is mirrored on their lambent surfaces, beneath which lies a menacing secret: for what first might appear to be a refreshing pool in an arid terrain is only a thin film of water obscuring an abyss of sticky bitumen, which has been oozing steadily from petroleum-bearing rock formations deep beneath the earth.

These are the notorious La Brea Tar Pits and since the days of the Pleistocene their peculiar configuration has served as both death trap and mausoleum for thousands of creatures–great and small, thirsty and merely curious–who venture into them and get stuck in their viscous pitch. Like a giant version of the ‘cockroach motel,’ once they ‘check in’ they never ‘check out’ and indeed the thrashing and bellowing of trapped victims attracts predators, whose natural wariness proves no match for the promise of an easy meal, ensuring they too are quickly doomed after jumping in for the kill. And so for thousands of years, whole conglomerations, entire food chains of animals have met their ends here: predators and prey sinking down alongside each other, each creature naïvely repeating the fatal mistakes of its predecessor: sabre-toothed cats and Dire wolves, with fangs and claws sunk into the contorted bodies of mastodons and camels, all of them frozen in elemental struggle as if in some Classical frieze. Not even the carrion eaters escaped the gruesome fate. Outsized vultures, giant condors and hideous, meat-eating storks, wheeling and squabbling for landing rights on the bloated corpses and almost corpses, snagged themselves when a carelessly extended talon or trailing pinion made contact with the merciless tar, that pulled them in, flapping and screeching , never to fly again. As well as being deadly, the tar has miraculous powers of preservation. The seething, interconnected beds of bone that have accumulated there have kept scientists busy ever since they first started excavating back in the early 1900s. Many of the rich paleontological finds are on display at the adjacent George C. Page Museum.

When I was a boy in Toronto back in the early 1960s, a small piece of the La Brea Tar Pits was on display in a dusty diorama at the city’s Royal Ontario Museum. This was a few years before the ROM adopted the loathsome trend for ’interactivity’, which consigned much of the museum’s extensive palaeontology collection to back rooms, out of public view, and what we got instead was an ersatz mishmash of mood lighting, audio tape loops and fibreglass models of dinosaurs standing aura-less amid plastic palm trees. Anyway before all that stupidity, I remember how transfixed I was ‘just looking’ at the thing itself, without being told how to think about what was in front of me – the tea coloured skeleton of a sabre-toothed cat, its outsized canines filigreed with tiny age cracks, poised to stab the neck of a hapless ungulate (a proto-camel? an extinct horse?) which had already begun to sink. It was the futility of it I remember the most, that both animals died together in the same inescapable way, the first doomed by thirst (or bovine idiocy), the second by carnivorous savagery. And I knew this scenario was to play itself out again and again because it was elementally and inherently unavoidable. Presiding over the sad scene was a tromp-l’oeil painted backdrop of a clot of vultures, hanging like wind-ripped umbrellas in the branches of a skeletal tree, and in broad brush strokes, a distant herd of mammoths melting into the horizon.

When I finally, this spring, got to tour the La Brea tar pits firsthand, I couldn’t help but see them as a kind of trope for contemporary times.

LA is a strange enough place to begin with–its palm-studded freeways and rivers of twinkling windshields pouring into the heat haze of the hyper- illuminated horizon–a place at once banal and startling, the High Baroque of American drive-thru suburbia amid scintillating beaches flooded in a golden, Canaletto-esque light. There are people there, of a certain age, whose faces have been so surgically altered it is as if they’ve been sucked through a magic wind tunnel. The mismatch between their wrinkle-less heads and the sun-withered bodies is chimerical, as if bands of Surrealist ‘exquisite corpses’ had gone AWOL, pulling themselves off the canvases and walking around. Los Angeles is the very essence of the American Anthropocene and yet prehistory bubbles and belches everywhere just beneath the surface. The city sits astride a massive oil field, where serried ranks of mini malls and tract homes lie nestled in the napes of brown hills and rustling eucalyptus groves, the edges of which bleed into a kind of terrain vague of ponderously nodding pump jacks tirelessly sucking petroleum out of a deposit dating back to the Miocene– a geologic epoch already long gone by the time the first mammoths sank into the tar.

Wandering through the pleasant grounds of Hancock Park, the past becomes the present and one soon encounters a pair of giant, chocolate-coloured ground sloths, like outsized Easter confections, placid and dim-witted in expression, yet armed with menacing fore claws that could easily rip the face off almost any attacker. As late as 10,000 years ago, these ungainly beasts lumbered across what was a vast North American range – their remains having been found from the Yukon to Mexico. At La Brea, they were regular victims to the suffocating tar.

yours truly and the ground sloths

In a still bubbling tar pit encircled by construction fencing, a family replica of gigantic Columbian mammoths replays a pathetic tableau. An adult is hopelessly stuck in the pit, its mouth agape in panic, its trunk frozen between the great curved brackets of its tusks, frantically gesturing to its mate and calf who stand helplessly on shore. The theme of serial entrapment and the futility of instinct gets amplified as soon as one enters the museum, which is packed with reconstructed skeletons and glass cases full of phylogenetically arranged remains, memorializing the legions of hapless creatures who died there over thousands of years, who just couldn’t stop themselves from making the same fatal mistakes over and over, in a senseless and recurring cruelty against which no benevolent god or Walt Disney narrator would intervene to warn ‘Stay out of those pits, yo!’ If only Spielberg had been in charge…

In paleontological terms, the tar pits are what is known as an ‘evolutionary trap.’ These create a stimulus that certain species are unable to resist and the results are often fatal. A contemporary equivalent has been the sad epidemic of dying albatrosses we’ve been seeing on Pacific Islands, their body cavities packed with bits of plastic that they seem programmed to snatch up from the waves and swallow in place of their natural food. Like the victims of La Brea, they just can’t help themselves.

Back at the Tar Pits, the Dire wolf (Canis dirus) seems to have been a particularly slow learner. To date the remains of over four thousand of them have been found there with doubtless many more to come. One of the more impressive displays at the George C. Page is a long, back-lit display, like something out of a high-end shoe store, containing hundreds of Dire wolf skulls, each an embodiment of one individual’s lack of impulse control. It seems that whenever a pack of them came upon an animal in distress in the tar, they would pile right on in on top of it, dooming themselves by their own overly developed killer instincts and susceptibility to peer pressure. The fact that the Dire wolf seems to have been exceptionally competitive, didn’t help matters. Males in areas where there was high population density developed outsized fangs with which to fight each other. It’s hard not to imagine the pack dynamic being a rather savage affair, especially when they chanced upon a bleating animal, trapped in tar. For the Dire wolf, there likely wasn’t a lot of time for second guesses. Though heavier and likely much meaner than their little cousin the coyote (Canis latrans), the Dire wolf failed to survive the Pleistocene, while the coyote still thrives in LA’s hills and canyons, feeding on what it finds in trash cans and snatching up unguarded pets. Though the Tar Pits weren’t the only factor in the Dire wolf’s continent-wide extinction, the evidence of its behaviour at La Brea indicates an inherent inflexibility, which must have been a major handicap in what, at the end of the Pleistocene, was a rapidly shifting set of conditions including changes in climate and the incursion of the first Paleo-Indians into its environment, who competed aggressively with the wolf for prey.

dire wolf skulls Though we may think our species’ ability to show foresight gives us particular resiliency–after all we started out in minuscule numbers, survived an Ice Age and proceeded to take over the world–we find ourselves now under a similar delusion to that which befell those hapless beasts at La Brea. Could it be that in the black, viscous materiality of petroleum we have finally met our match? Though we may think we have mastery over our fate, we seem blind to the possibility that it might be a substance that has control over us…

As an evolutionary trap– a nemesis–petroleum is the perfect agent. It is the very essence of death, a distillate of corpses from untold myriads of prehistoric organisms, which has quietly waited for us beneath the earth. If substances possess their own agency, as Jane Bennett surmises in her (2010) Vibrant Matter, is it so far-fetched to suggest that petroleum is luring us in, manipulating our innate behavioural vulnerabilities to ultimately absorb us into its oozing corpus? Like the sabre-toothed cat and Dire wolf before us, petroleum has exerted its ability to hypnotize, to communicate directly with our vulnerable animality, bypassing our much vaunted capacity for reason and discernment. It’s not that big a leap from the Tar Pits to the Tar Sands…

As happened to the Pleistocene creatures who got stuck in it when they put aside their caution, petroleum–ever protean– has set its exquisite trap for us in the form of a fata morgana, which gives us the illusion of eternally abundant and convenient energy with no long-term consequences. We are probably already in too deep to realize what has happened; that we are becoming petroleum, absorbed by the wily substance to become one with its subterranean deposits.

The Anthropocene might be remembered as a geologically brief period during which our species was allowed an overdraft, a blip during which we extracted a quantity of the black ooze before we had to repay our loan with the highest of interest; our lives, and those of the countless other organisms we took with us after we have made the planet uninhabitable. In so doing, we are offering up billions of putrefying corpses, untold tonnage of petrochemical garbage and entire landscapes of withered vegetation to be re-incorporated into the geologic, where unstoppable tectonic regimes will reprocess it into the mother of all oil fields.

So it is a mistake perhaps to wax too moralistic about our failure to rein in our natural impulsivity, to plan sensibly or imagine a future free from our addiction to this substance. Our connection to it might be too deep, too genetically encoded for us to resist through mere self critique.

Following the logic of the Dire wolf, our own species is competing increasingly viciously for what is (for the geologic moment anyway) a limited resource. The power elites in localities dependent primarily on petroleum production (Russia, Nigeria, Libya and others) have drawn whole societies into animality and impulsivity.

Even Canada, long a role model for liberal democracy, has slid into this petro-brutality. Under the prime ministership of oil-mad Stephen Harper, its government has declared a totalitarian war on scientists who study climate change and associated environmental contamination. The uncomfortable facts they keep bringing up highlight Canada’s abysmal record on these matters, which, aside from being an international embarrassment, threaten to push the usually complacent Canadians into a confrontation with the ecological Real (boring!, depressing!), invoking questions the Harper government is determined not to let us ask. Important and long-standing research facilities and environmental monitoring stations have already been shuttered, their scientists sacked and the scholarly material packed away or even thrown into the garbage. Those few scientists still working have been given STASI style minders, through which all communication with the public must be vetted. They even shadow the scientists at academic conferences to make sure they don’t say anything deemed ‘off message’ to the government’s single-minded agenda.

Yet given that our attraction to petroleum is demonstrably biological, can we really blame the individual oil worker, warlord or myopic Canadian bureaucrat? By doing their part to hasten mass extinction, they are in the service of the long term interest of petroleum itself. By extending its sticky tendrils through a higher dimensional space than most of us are letting ourselves imagine, petroleum assumes the characteristics of what the philosopher Timothy Morton calls a ‘hyperobject,’ an entire set of relationships, interactions agencies and desires of which we are but a small and transient part.

tar sands (via National Geographic)

dwarf birches and tundra  suddenly – reindeer!

The morning broke grey and brooding outside the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station and after a quick breakfast, we were on the trail, hiking up Saana Fjell, guided by Erich Berger of the Finnish Bioart Society. The idea was to familiarize ourselves with the geology, ecology and cultural history of the vicinity so we could dive into our research plans as soon as possible.

The Australian bio-hacker, Oron Catts had already been here for a week to do some scouting for his group’s ‘Journey to the Post-Anthropogenic’ project. They planned to perform a comprehensive bio-archeological survey of the crash site of a German Junkers 88 bomber that came down on Saana in 1942, which included a metagenomic analysis of the plane’s debris field and a recreation of the crash trajectory using a remote-controlled drone.

debris field It wasn’t long before we passed the tree line where the mountain birches gave way to an expanse of open tundra sweeping out before us in a swath of russet heath and exposed rock, with quivering patches of silver cloud here and there snagged on the crenellations of the topography. As if on cue, a small herd of reindeer appeared over the crest of a nearby hill and galloped across our field of view, cocking their heads as they past us and then just as quickly melting into the gloom of the opposite horizon. It is hard to judge distances here in this cold desert. An unusual rock formation in the distance might be small and quite close by or enormous and very far away.

I felt for a moment as if I had been transported back to the Pleistocene, as the landscape I was looking at was what much of Europe and North America would have been like at the end of the last Ice Age, though (other than the reindeer) there wasn’t any of the charismatic megafauna such as the woolly mammoth and the cave lions I would have had to concern myself with back then. Semi-domesticated, reindeer have sustained the local Sami people since ancient times and they are of the few creatures (other than snails) to manufacture the enzyme lichenase, enabling them to survive on lichen during the winter months.