It’s that time of year when the days are short and the color has been sucked from the world.

I woke up this morning to find an egg lying out in the snow. Even the air has changed somehow, stuffing my ear canals and sealing me into the blood-throbbing confines of my memories. I think of last spring and the redwood grove I saw, ancient and sighing, oblivious to the sliver of time in which I must be satisfied. Yet there among the swirling gloom had grown the child of their ghosts, its needles white as a tapeworms, glistening with formaldehyde. It tried to kill me, you see, and hurled a branch in my direction when I got too close. And now after all those months, the great gray quilt of sky has pulled down over me and breath itself seems difficult. But high above the ragged trees, the white wraith swans churn savage wings again toward the ends of time. With bleating songs of ice and metal. I thought they’d gone extinct. . .

|

||||||

|

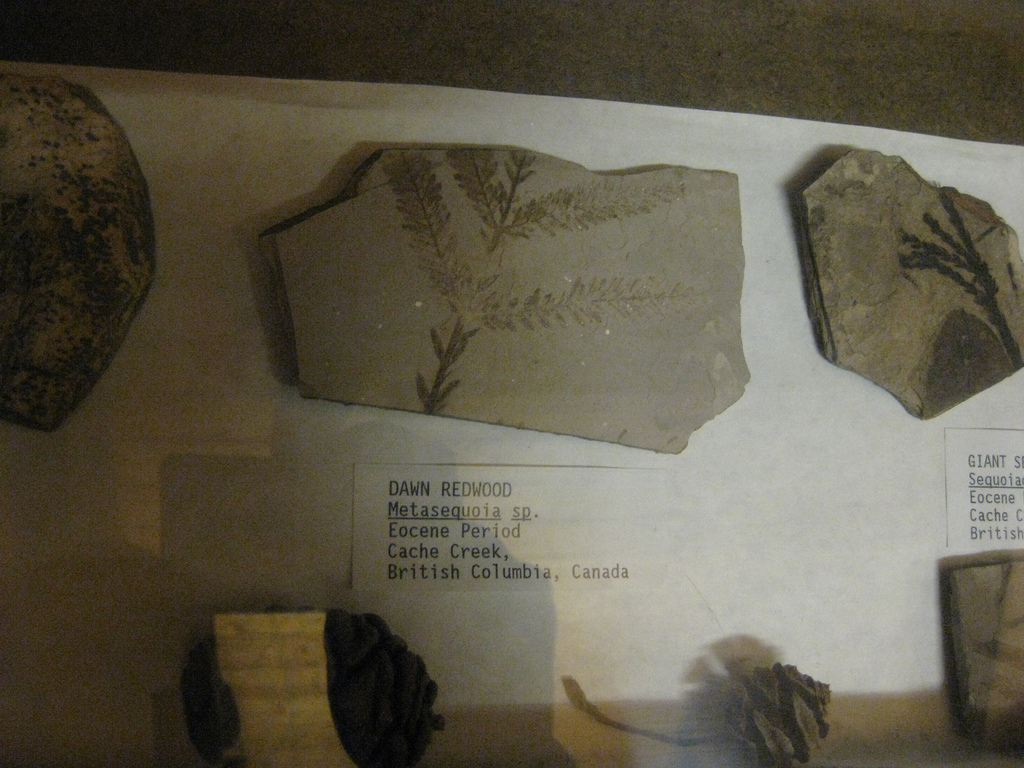

With the record-breaking heat wave that is currently withering Southern BC, I am starting to wonder just how hot it’s going to get when climate change really starts kicking in. The temperatures we suffered through this week made it feel like we’re already well on our way. Some estimates indicate that our planet might be on its way toward a thermal maximum not seen since the Eocene era – some 55 million years ago. Back in those days, palm trees and alligators flourished as far north as Alaska and the Canadian Arctic. Much of what is now British Columbia was cloaked in a warm temperate forest, far more biologically diverse than what we have today. Imagine groves of such exotic trees as Dawn redwood, Gingko and Cunninghamia growing natively over a vast swathe of Western Canada and down into Washington and Oregon. Their leaves, seeds and flowers are preserved in exquisite detail in the fossil deposits of various localities from Cache Creek to Kitsilano. Some of these trees still survive, albeit in much diminished ranges, in parts of China and the southeastern United States, but a long-term cooling trend extirpated them from our own forests long ago. Yet if global warming is threatening to bring back Eocene temperatures, why not reintroduce the Eocene forest? Many of our native trees are already suffering under the newer, hotter conditions, as is evidenced by the plague of pine beetles ravaging the forests of the Interior in response to milder winters. We can only hope that the native trees will survive by retreating northward, but the pace of warming is predicted to be rapid so it will be hard for natural plant migration to keep up. Over the past dozen or so years, I have been introducing into my yard some of the tree species that once comprised British Columbia’s Eocene forests and I’ve been tracking their progress. Metasequoias in particular have done spectacularly well and a couple of my ten year-old specimens have reached 8 metres in height. These are amazing trees, deciduous conifers long thought to have been extinct, that caused a sensation when they were found surviving in a remote part of China, back in 1944. Their fossil remains are distributed all over the Northern hemisphere, from mid latitudes right up to the High Arctic, where their deciduous needles might have conferred them an advantage during the long, dark winters. Other Eocene trees I have successfully grown include Tetracentron, Scadiopitys, Cunninghamia, Podocarpus, Sequoia and Trachycarpus palms, all of which have flourished without winter protection, despite frosts as low as minus 15C and frequent deep snow. Members of the Juglans family (hickory and walnut) have also adapted well to my locality and I am steadily introducing other Eocene species to see how well they do. Last year, I embarked on a collaboration with the botanist Rupert Sheldrake to scale up my initial trials to a landscape level. I initiated the planting of entire groves of Metasequoia, Juglans, Gingko and Coast Redwood, arranging them in clines, or habitat gradients on Rupert’s property – a 60 acre clear cut on the east side of Cortes Island. Though the winter of 2008 and the beginning of 2009 have been exceptionally dry, a good portion of the plantings have so far survived without supplemental watering. The Juglans and Sequoia in particular have taken well, on what for the most part is a very exposed, site, heavily disturbed by industrial logging. Work on the “Climate Change Forest” is ongoing and our hope is that the successes and failures we have in establishing formerly native tree species will yield useful information on the future of forests under conditions of global warming. Perhaps some of the trees might have a kind of genetic memory and will once again flourish here as they did so many aeons ago. If so, our reintroduction of these Eocene survivors might prove part of a larger strategy to manage the climate cataclysm we have only just begun to experience. Spending winter on the west coast of Canada is like living in a giant car wash with all the lights turned out. Spring however, comes relatively early, with the pussy willows and hazel catkins often making their appearances already by the end of January. By the time February is over, the crocuses have usually poked up their cheery little heads. Viburnum bodnantense is another extremely early shrub. Its pink flower clusters have a scent that reminds me of vinyl doll heads dipped in sugar. Though it is one of the world’s most rapacious consumers of wood, Japan worships trees like no other place I’ve been to. Where else would such love and attention be lavished on a couple of four hundred year old plum trees, which, left to their own devices would have up and died ages ago? There is something intensely poignant about these venerable plums, brought from Korea back in 1609, to Matsushima’s Zuiganji temple. To keep them alive, the rotting trunks have been heroically patched with cement and the saggy, senescent branches propped up with poles. The trees are like ancient pets tended to by generations of Zen Buddhist monks, who are born and die in the span of time it takes the plum tree to accumulate a few infinitesimally thin growth rings. And the payoff? What is it exactly? A few ephemeral blossoms, pink and white, to herald the end of a long winter. It is heartening to know that despite the hundreds of years of turbulence, of typhoons, fratricidal wars and pestilence, an unbroken line of caregivers has thought these trees to be worth their attention. To be sure, the Japanese sense of duty must have had a lot to do with it, but there is something else too: a kind of appreciation of the fragile that in my mind has no equal anywhere else in the world. One of the great things about visiting Japan (for a tree geek like me) is being able to see some of the many old Ginkgo trees that are growing here. The Ginkgo, as some readers of this blog might recall, is a kind of living fossil, the last remaining species of a genus that was once widespread. Everything about the Ginkgo tree is strange. No one knows exactly when, or even if, they actually ever really went extinct in the wild and there is some evidence to prove that all the ones alive today are descendants of a few trees rescued in antiquity by early Buddhist monks. Ginkgo is one of the few trees that produces sperm that actually swims. And then there is this matter of the chichi or Gingko nipples, which form on older trees. Their function isn’t clear but it seems to be a kind of aerial root; an upside down version of the ‘knees’ one sees on the bald cypress trees (Taxodium) that grow in the swamp lands of the south-eastern United States. I photographed these wooden wonders that were dangling from a few of the Gingkos lining the approach to Tokyo’s controversial Yasukuni Shrine. Outside Asia there aren’t too many Ginkgos old enough to show this curious morphology. The term ‘nipples’ just doesn’t seem adequate to describe such girthy protuberances.  Japanese Mountain Yam  Ambassador Bridge, Windsor, Ontario. Well OK. It’s been a long time in coming. And as usual life has been full of endless distractions, all of which have been convenient as excuses that have kept me from posting to THE SHOW SO FAR. Frankly, I had been thinking I would give the whole thing up. Then the e-mails started coming in. It seems that some people actually *read* this thing and want me to continue. Yet still I resisted. What ultimately brought me back here was the discovery of this winsome little tuber. The Japanese mountain yam had been a kind of holy grail for me, resisting all of my previous attempts at its cultivation, here on this damp, cold little Canadian island. But I just hadn’t been patient enough. I planted this one from a little sliver over three years ago and then completely forgot about it. One day in early October, I was weeding my cold frame–And there it was! Perfect. Wonderful. It had been growing underground all this time. The mountain yam or yama-imo is unusual among yams because it is traditionally eaten raw. We ate ours sliced with a little plum paste and shoyu. It tastes deliciously cool and a little slimy. If you click the above link you will no doubt be *amused* by its surprising non-food uses!  I have been on the road a lot, giving lectures at colleges on my ‘botanical interventions’ projects, starting with a gig at the Artists Urban Plans conference in Windsor Ontario, followed by NYU, Smith College and UBC’s Interdisciplinary Studies department. And it’s not over yet. Engagements in Japan and Florida are coming up in the New Year. It feels a little odd that there is such a sudden flurry of interest in my work, because, after all, I’ve been doing these things since the mid 1980’s. Still it’s great to be out there meeting other practitioners. The Green Corridor project, which co-hosted the Windsor conference is a particularly remarkable initiative. Organized by Ontario artists Noel Harding and Rod Strickland, Green Corridor is a large scale, multi-disciplinary attempt to integrate artists, planners, and technical people into the greening of the main thoroughfare that connects Windsor to adjoining Detroit, Michigan: the busiest border crossing in Canada.  Nepenthes x coccinea  Sarracenia alata  Sarracenia leucophylla I have always been fascinated by flesh eating plants, ever since the day when, as a small boy, I proudly came home with a little Venus Fly Trap I had bought with my allowance money at the Canadian National Exhibition. While this first specimen soon died as a result of my misguided ministrations of greasy hamburger meat and hyper-chlorinated Toronto tap water, I was already hooked.  digested insects in pitcher  wasp entering But how does the pitcher plant actually *digest* the prey that it captures? The truth, as it turns out, is complicated and interesting. The New Scientist recently ran an article describing how the closely related Sarracenia purpurea (which I also grow) contains an entirely self-contained aquatic ecosystem in the fluid at the bottom of its pitchers. Here mosquito larvae act as top level carnivores that consume the plant’s prey insects after they fall into the pitchers and drown. The larvae of these Wyeomyia mosquitos can exist only within these tiny pools of fluid and have never been found anywhere else. Bacteria, rotifers and protozoans then feed on the larvae’s leftovers (as well as being themselves eaten by the larvae) before *their* wastes in turn are absorbed by the plant as its food. These little ecologies are being used by scientists at the University of Vermont to develop computer models to help understand the effects of disturbances, such as habitat loss and climate change, on larger ecosystems

Medlar grafted to a hawthorn

close up of whip and tongue graft To the delight of plant geeks everywhere, MAKE Magazine has put out a HACK YOUR PLANTS issue (Vol 7). I’ve been a phyto-hacker for years and reading this magazine made me feel all warm and fuzzy. Here are the results of a cool inter-species plant hack I recently performed by grafting the scion from a medlar (Mespilus germanica) to a feral hawthorn tree (Crataegus monogyna) Why? you might ask. The Medlar has a fruit that tastes (to my mind) rather like sugar-frosted baby shit, (although I’ve been told by people who like it that I should give it a second try.) The medlar has historically been used as a kind of metaphor for prostitution or ‘premature destitution,’ a quality which makes it oddly endearing to me. And, I couldn’t resist trying an Inter-species graft, just to see what would happen. I haven’t been able (yet) to produce the elusive +Crataegomespilus graft chimera, which I wrote about back in March 2005, but at least I now have what looks like a viable graft union, from which the chimera might one day sprout. I will just have to bide my time a little longer to see if this exquisite botanical monster eventually appears.

Medlar, Mespilus germanica, Cortes Island 2006 |

||||||

|

Powered by WordPress · Atahualpa Theme by BytesForAll |

||||||