|

|

I found this charming old picture in a box of junk, its original provenance long forgotten

It has an aura of lightness and optimism that seems almost archaic now.

The winged sprite, with her impish black mask flitting around a paper Eiffel tower, has doubtlessly long ago disintegrated into dust. The photographer who took the picture, the person who fabricated the cheerful display and the customers (who jauntily dabbed Scent de Paris behind their ears and onto their bosoms) are likewise all (probably) dead.

Were they happy?

Did Scent de Paris infuse them with ‘jouissance’?

Sometimes, when things move forward, they can no longer go back.

A diode works that way. Current can only flow through a diode in one direction. It’s an interesting property of semiconductors. Old style diodes were sometimes called ‘valves’ for that reason.

The human life is like a diode, through which time can only flow in one direction.

Yet we try to achieve our goals. We are a goal obsessed society and are encouraged to stay “goal oriented” and “focussed.” The following of tangents is not encouraged, even though in the greater scheme of things, it is these tangents that can be the key to our survival. Tangent following is a basic mechanism of evolution.

Sometimes the things most worth looking at, just creep in at the side of our gaze. That’s the problem with focus – you miss a lot of interesting stuff.

Night vision is a case in point. In order to see better at night, you have to train your eyes to go crosseyed. In fact there are people who train themselves to develop their night vision to get into a kind of altered state.

Their website contains this reference to The Book of Five Rings, in which:

The Book of Five Rings, Miyamoto Musashi, the legendary swordsman of 16th century Japan, implies that he fought his greatest duels with his eyes crossed, and goes into considerable detail about developing and using this strange ability. He writes somewhat mysteriously about a state he entered while so engaged. He also refers to the two types of sight which he calls Ken and Kan. Ken registers the movements of surface phenomena; it’s the observation of superficial appearance. Kan is the examination of the essence of things, seeing through or into. For Musashi, Ken is seeing with the eyes, Kan is seeing with the mind, a difference paralleling that between style and substance. He gives instructions for developing Kan sight: “It is important to observe both sides without moving the eyes. It is no good trying to learn this kind of thing in great haste. Always be watchful in this manner and under no circumstances alter your point of concentration.”

The nightwalkers say that :

The whole secret to mastering peripheral awareness is keeping one’s visual attention independent from focused vision.

Plone has been in my peripheral awareness for quite some time now, as a way to organize the documentation of my work and to interact with the communites that exist around it. I have been resisting creating an internet accessible archive for years now, mostly because I haven’t found a comfortable platform in which it can exist. I need to disseminate but also to facilitate the creation of an interactive community *all within the context of the site*. I have started building my Plone site, which has vaulted me into a whole new universe of learning. I am taking baby steps towards learning the vicissitudes of Zope and OSX’s ‘terminal’ program and will be uploading my prototype site to a plone-friendly server shortly.

I’ve also been helping take care of an advanced Alzheimer’s patient (my mother-in-law) for a while now, which has got me thinking a lot about memory. While we tend to think of memory as the domain of higher life forms, BBC World recently broadcast an item about the amazing memory of fishes.

According to this report:

Now, fish are regarded as steeped in social intelligence, pursuing Machiavellian strategies of manipulation, punishment and reconciliation, exhibiting stable cultural traditions, and co-operating to inspect predators and catch food.

apparently:

“fish (are) the most ancient of the major vertebrate groups, giving them “ample time” to evolve complex, adaptable and diverse behaviour patterns that (rival) those of other vertebrates. These developments warrant a re-appraisal of the behavioural flexibility of fishes, and highlight the need for a deeper understanding of the learning processes that underpin the newly recognised behavioural and social sophistication of this taxon.”

Which leads me to wonder:

Maybe we are short-changing *many* other life forms by underestimating their intelligence. While they may have a relatively small number of nodes in their neural nets, the level of connectivity between nodes is probably pretty high. Also with creatures like fish that live in schools or swarms, each individual is a node connected to many other individuals creating a giant component or giant cluster, very quickly. Linked by chemical trails or (in the case of fish) lateral lines, schools of fish can respond en masse (and in an instant), to minor disturbances in the water.

The closest I have ever come to this experience (or rather its human equivalent) was standing in the middle of Tokyo’s Shinjuku Eki (train station) at rush hour. Shinjuku Eki handles 3 million passengers a day. Standing in the midst of a vast corridor seething with humanity, I was dazed by the spectacle but *not a single person bumped into me.*

Ipomea platensis, (ten years old)

I’ve been trying to tidy up and organize my chaotic workspace and have found it hard to reduce the amount of *clutter*, much of it of a botanical nature, that perpetually surrounds me.

An inveterate anomophile, I’ve always been attracted to a certain qualities of freakishness and monstrosity in nature (and in people). These phenomena ellicit in my a kind of frisson that is hard to describe. It’s a kind of deep, biological excitement that tweaks me on an autonomic level. I just have to be around it.

To help feed this predilection, I maintain a small collection of caudiciform succulents, (most of them originating from the drier areas of Madagascar, South Africa and South America), which spend the cooler months of the year in my office. Caudiciforms have bloated and swollen stems which store moisture so that they can survive through many months of drought. These stems vary from almost spherical, to bottle shaped, to anthropomorphically lumpish forms reminiscent of some kind of botanical incarnation of the work of Henry Moore.

Mostly slow growing, caudiciforms usually remain in dormancy for the greater part of the year, occasionally deigning to put forth a leaf or sometimes even a flower, when atmospheric conditions (or deep genetic clock signals), trigger them to do so. Growing these plants is mostly about waiting, and contemplating long time cycles, punctuted (occasionally) by sudden excitement, when they actually *do* something. What they lack in rampancy, they make up for in longevity.

In fact the oldest potted plant in the world is a caudiciform, a veteran Fockea crispa which has been residing in a glass house at the botanical garden in Schonbrun near Vienna since 1794. Gordon Rowley in his inimitable book “Caudiciform and Pachycaul Succulents” (1987) details the amazing history of this plant in a prose style that is truly beautiful:

” One of the most celebrated collections of exotic plants among many in Europe at the end of the eighteenth century was that at Schonbrunn, two miles southwest of Vienna. The palace and superbly landscaped grounds are still an attraction to tourists today. In 1753, the year that Linnaeus introduced binomial names for all plants and animals, the Empress Maria Theresa commissioned a Dutchman, Adriaan Stekhoven, to construct a menagerie, botanical garden and range of glasshouses on the imperial estate.

Schonbrunn managed well until 1780, when one freezing night in November, disaster struck. The boilers were out and by the time this was discovered and put right, many of the tender exotics had frozen. However the new Emporer Joseph II was determined to make good the losses and summoned two young Austrians, Franz Boos and Georg Scholl, to explore Mauritius and the Western Cape in search of new plants. This they did with conspicuous success.

Among the many novelties dug up by Scholl was a lumpish, turnip-like caudex about 30cm long, covered in buff-colored bark and erratically disposed pimples. Potted up at Schonbrunn, it grew slender twiggy shoots with opposite, elliptical leaves of glossy dark green with a distinctive crisped margin.

Fockea commemorates Gustav Waldemar Focke, an obscure doctor and plant physiologist of Bremen, not the more deserving systematist and authority on hybrids- Wilheml Olbers Focke of a later generation.

Efforts were made to propagate it. It was a messy plant to handle, exuding copious white latex wherever bruised, and the cuttings failed to root. Neither would a single plant set seed, without a mate of the opposite sex: it turned out to be dioecious.

So it remained for decades the only known specimen, and legends grew up that it was the last survivor of an ancient species. Surviving the Napoleonic Wars and later two World Wars, it was still thriving when I photographed it in 1963: the oldest caudiciform in captivity and indeed the oldest potted plant in the world. A recent report by Zechner (1984) states that it is still thriving and that its flowers, produced annually in October, smell sweetly and attract hoverflies, although I have not heard any reports of seed setting.”

(I wish I could write like that. Rowley is truly one of the great botanical anomophiles)

But then again, plant evolution is an *emergent* system which evolves complexity through iterative cycles of feedback and adaptation. Steven Johnson in his book, Emergence describes software that follows this organic model, literally designing itself to solve complex problems. The programmer, (supercomputing legend Danny Hillis) says, there is “no simple explanation of how the programs work than the instuction sequences themselves. It may be that the programs are not understandable.” These “bottom-up” programs function “less like engineering a machine, “than baking a cake or growing a garden.” They are essentially, “Gardens of Code.”

Well everything old is new again, which is quite reassuring. I’m sure that the ancient Fockea of Schonnbrun is smiling beatifically in her pot.

check out Baudrillard’s

L’esprit du terrorisme [The Spirit of Terrorism]

for a reality check on 9/11.

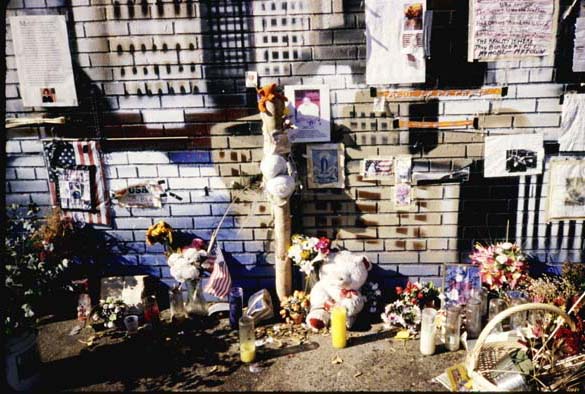

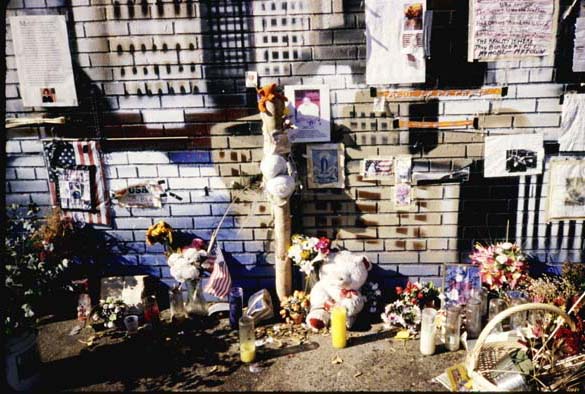

near Ground Zero

impromptu shrine, Lower East Side

It’s the end of summer and I am sitting in my car, waiting for a ferry and looking at a limpid, grey sea. Big black vultures are spiraling lazily above me, riding the thermals, wafting up from the tarmac, on their ragged wings. They are seeking death with the quiet urgency of those who know its inevitability, traversing through the vast columns of moving air that define their universe, with nonchalant ease. It will come, and they will feed.

vulture diorama at American Museum of Natural History

I’m re-reading Martin Bax’s The Hospital Ship and am once again struggling with the great nagging questions of “Are we fucked?” and “How do I get myself organized now that summer is over?”

Bax’s book posits a hospital ship in some period in some parallel reality that is plying the seven seas, in the middle of a vast pandemic of violence. People are slaughtering each other everywhere (literally crucifying each other), and piling up the casualties on the quays. Nobody really knows what’s going on and the news coming in by radio to the ship is disjointed and contradictory. The reports are all transcribed on paper and pinned to a wall but sadly:

There seemed to be a chronic shortage of pins to fix up the reports, so that in consequence they blew away and anyone in the stern of the ship could reach out a hand and collect bulletins from the air as they drifted by in an endless paper-chase over the stern of the boat and on into the sea

I see in this passage an uncomfortable parallel to my own struggle with personal organization. – Incoming bulletins frequently fly off of the metaphorical boat and on into the sea, and I start to lose track of the big picture. I manage to snatch a few bulletins from the air as they careen by, and this becomes the basis for my blog, but mostly they wind up floating on the grey waves, gone forever. What I am managing to piece together, doesn’t look too good. Like the world described in ‘The Hospital Ship’, I’m beginning to think we are fucked.

Sometimes the information that was thus collected seemed to suggest that business was much as usual all over the world, while at other times the suggestion was that total collapse had already occurred.

Bax nailed it, and many of us increasingly feel it. The constant lump in our throats, the shortness of breath and the deep sadness. The constant attempts to pin down some transient bits of reality before they evaporate into nothing. At least we have our blogs . . . Perhaps total collapse HAS already occurred. Some ecologists place the point of no return somewhere in the 1980’s. It has to do with the collapse of Antarctic iceshelves of an order of magnitude never seen before in human history. Maybe we should feel somehow strangely liberated. At least we have certainty. . .

But how do I organize my handbasket, as I careen in it towards hell? I think about this all the time. . .

My friend Laura has given me new hope in that direction. She has shown me the brilliant work she is doing using Plone and Zope– prodigious open source content management systems that seem to hold great promise. The websites that she creates with these tools cool the fevered brow of my organizationally challenged mind with reassuring rows of tabs and elegant, transparent, immediately comprehensible architecture. I must learn how to use these tools soon, before I descend into deep entropy. It is so easy just to drift . . .

and

As a result, I can’t help feeling a bit twitchy. Perhaps its my ‘R’ complex. ‘R’ for reptile, the lizard mind that straddles just above the core of my neural chassis. Lizards appear to experience things more or less directly, without the burdensome freight of intellect. They process their perceptions, predominantly with their ‘R’ complex. This pre-lingistic pattern-recognizing mode can get deeply fried by the constant flux of bulletins pouring in from the cerebellum. The world’s highest paid executive coach , told me (how this happened is a long story, best saved for another posting) that I “think too much”, and maybe he is right. Maybe my sense of ‘self’, is getting in the way of happiness. But somewhere in there beats the heart of a lizard. And lizards have lived through a few mass extinctions . . .

Recently, after feeling a little overwhelmed, I took off all my clothes and jumped into the ocean, hoping it would help me ‘re-boot’. This in itself is not as radical as it sounds, in the cultural Galapagos which I call home. Clothing is optional at the beach. In fact, there are some people around here whom I don’t recognize with their clothes *on*. The water was cold and I soon emerged to bask, naked on a rock ledge. Somewhat zoned, I let my gaze fall vacantly on the crinulations and tessellations in the rock and was startled to come upon a tiny eye winking at me from the darkness of a nearby crack. Was it my disembodied lizard mind?

It was a Northern Alligator Lizard, engaged in the same thermotropic behaviour as me. Basking. A lizard at the northern extreme of its range. At this latitude they have adapted to the cold by becoming live bearing, ensuring the survival of their heat-loving young by sitting for hours in the weak northern sun.

So we had a moment of poikilothermic bonding, and I tried to cast my mind back to what I might have been thinking during the Triassic. I moved my head and the lizard skittered away.

I guess it panicked . . . .

Northern alligator lizard, Vancouver Island, British Columbia

(not a limp dick)

I suppose it is inevitable for the time of year. Perhaps it is the sense of the long summer waning, its once endless expanse of days, now finite and running out like grains of sand in an hourglass.

Since childhood, I have experienced late August with a sense of foreboding. The shortening days and lengthening afternoon shadows were inevitably the unmistakable harbingers of irrevocable and systemic changes. The reality of the upcoming school year would suddenly loom like an oncoming ship, emerging from the quiescence of a fog bank. The languidity of summer seems to evaporate overnight into sharp little crystals of urgency. The nightly chirping of crickets is a little more frenzied now, signaling perhaps the end of unstructured time – at least for this year. The end of the endlessness of the season of the sun. Like it or not, the universe is shifting its gears. We must choose between frisson and dread. Somewhere a demon figure is pulling the levers. Click Click.

In the clear warm night skies, Mars has been shining like a pulsing red beacon, the closest it has been to the earth in 65,000 years. Mars is after all, the god of War. The last people to have seen it this clearly were the Neanderthals, and they went extinct.

A recent trip to the idyllic seeming little town of Courtenay BC and I am approached on three separate occasions by sad looking middle-aged women, begging for change. Middle aged and formerly middle class, they have somehow fallen like dried leaves from the withering bough of the bourgeoisie – the walking wounded in the Class War. Twenty years of economic brutalism have become so deeply entrenched, that this no longer seems remarkable – even in Lotusland. After all, the fear of winding up homeless, keeps a lot of low-income workers from fighting for better wages or working conditions. Keep poverty visible and you have a very effective form of social control. It keeps the cost of labour down.

Brian Eno, the godfather of ambient music writes a wonderful review of John Stauber’s Weapons of Mass Deception, in the Guardian. Eno, who brought us the seminal 1978 Music for Airports is now helping to deconstruct the ubiquity of ambient American propaganda. This is truly wonderful and dementedly mimetic. I continue to admire him greatly.

Renana Brooks writes in The Nation about the use of studied ‘empty language’ techniques and ‘negative frameworks’ in George W. Bush’s speeches, to create an ambience of learned helplessness and inevitability in the minds of the American public.

I remember once, (years ago, under the influence of some hallucinogen), suddenly and viscerally appreciating the interplay of flows, chaos and turbulence in the boiling gray sky of a Toronto spring. This connection never left me. It’s easy once you open your mind to the large scale patterns. Deep inside, we’re wired for it. We can read ambience.

Outside I see the gray skeins of an oceanic front scudding across what has, seemingly forever, been a painfully white- blue sky. It might be the first rain in weeks. . .

One of the odd exigencies of living on the coast of British Columbia, is the moderating effect of the Japan or Kuroshio Current (the Pacific counterpart of the Gulf Stream), on our climate. While we are at 50 degrees north in latitude, (4 degrees north of Quebec City), it is possible to grow figs here. Several of them are ripening on a branch outside my window, where they look incongruously tropical against the backdrop of northern conifers.

While the fruits are oddly testicular in shape, the fig cannot reproduce sexually at these latitudes because we are lacking the tiny wasp that evolved to pollinate it. This might be just as well, as male fig wasps live out their little lives as wingless sex slaves which never get to leave the fig in which they were born. So our figs, sweet as ambrosia though they may be, are merely sterile ovaries which will never set seed.

Fortunately the trees are easily propagated asexually from hardwood cuttings, taken in the late winter

The fig is one of the oldest cultivated trees, going back to at least the Bronze Age in the region of Asiatic Turkey. It has the dubious distinction of being the first tree mentioned by name in the Bible. Its leaves were used by Adam and Eve to cover their genitalia after expulsion from the Garden of Eden. The fig was likely the ‘forbidden fruit’ from the ‘tree of knowledge.’ Jesus actually curses a fig tree and causes it to wither.

What did the Bible have against figs? Where they considered immoral in their deliciousness ? Was it the shape of the fruits? We may never know, but I for one will continue to eat from ‘the tree of knowledge.’ At least for the next couple of weeks.

tree of knowledge

Late summer is the season of moths. Every electric light left on at night seems to attract legions of them, relentlessly battering themselves to death against the bulb, shedding the fragile powder that covers their wings as they commit their tiny scorching suicides. Obsessively beguiled by the blinding brightness, it seems they just can’t stop themselves. Does any moth ever ask itself, “Why am I doing this?”

My old friend Neil recently reminded me of my favorite moth of all –

Mothra -, the mother of all moths, from the eponymous 1961 Japanese monster movie. He sent me an audio file of the Mothra song, sung by the Mothra twins, adorable miniature fairies that communicate telepathically with the ancient moth mother. In the first Mothra film, the twins (played by real life pop stars Yumi and Emi Ito ) appear in matching Chanel suits and jaunty Jackie Kennedy style pillbox hats. They try in vain to prevent Mothra’s giant egg from being stolen by evil businessmen from their home on Infant Island. What a great metaphor for modernity !

The original 1960’s Japanese monster movies were all about Japan’s loss of innocence as the first nation state casualty of the nuclear age. Godzilla himself, was a transparent trope for America – big and goofy, smashing up Japanese cities and withering the landscape with his radioactive breath. But nevertheless, he was kind of cute.

Like moths flapping at the window of a night-time kitchen, my tribe of WiFi enthusiasts in rural British Columbia clusters and presses against the side of a government building seeking proximity to a high speed data pipe. We bask in its flux of 802.11b, which like nectar feeds our ever increasing appetites for large downloads at high speeds.

WiFi Enthusiasts outside a rural British Columbia government building

When the weather is hot, the sky scintillatingly blue and the air throbs with insects, I inevitably find myself on a road trip. While on a recent drive from Vancouver, I found myself musing about the many other summer road trips I have been on. There is something exhilarating about hurtling through a vast summer landscape in a speeding car with the hot air blasting through the windows like a hair dryer and the infinite sky so intensely blue that it seems black around the edges.

I especially like to record the passing roadside landscapes with a movie camera and later hunt for images that I might have missed. A lot can happen in a thirtieth of a second.

Hanford Nuclear Reservation

Several years ago I found myself driving to Idaho via Eastern Washington to help Ruth do research on potatoes for her book, All Over Creation. I suggested we detour past the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, which has been called ‘The Chernobyl of North America, to try and get a closer look. In the distance, shimmering in the heat haze, we saw an ominous set of military gray buildings set on the arid, sage brush covered banks of the Columbia river.

The vast tawny rangeland between the highway and the nuclear reservation was ringed a security fence on which ‘do not enter’ warnings were conspicuously posted.

Since its inception in 1943, Hanford has been contaminated with “billions of gallons of radioactive waste” including plutonium, the most deadly substance known, which has been simply buried or is leaking into the ground from deteriorating metal tanks. Hanford was America’s first large-scale nuclear materials production site. The plutonium used to bomb Nagasaki was processed here and later was used to arm America’s Cold War nuclear arsenal. The people living down wind from the Hanford site, (who call themselves “the Down winders”) have sky-high rates of thyroid cancer and a resultant penchant for turtle-necked sweaters.

Ironically, this toxic Armageddon has become a wildlife paradise, supporting what National Geographic calls one of the “finest examples of shrub-steppe habitat” left in the Columbia basin. The Hanford Site is home to mule deer, elk, coyotes, badgers, rabbits, skunks, bald and golden eagles, herons, ducks, ground squirrels, several species of mice, lizards and three species of snakes.

There are also many species of rare plants. Some are endemic which is to say that they are found nowhere else in the world. A 1994 study covered only 30 percent of the Hanford Site but found 56 new populations of rare plants and discovered a completely new Lesquerella species. The 1994 study also found 205 species of birds on the Hanford Site, including 31 species of special concern, 72 species considered rare, and 9 species never before documented at the Hanford Site. Close to 1,000 insect species also were documented, including 19 species new to science and 200 species new to Washington State.

Why is there such astounding biodiversity in this toxic wasteland? It appears that for the survival of natural ecosystems, the absence of human beings more than makes up for the radioactive toxins that have been left behind by us. WE are the most powerful toxin. I riffed on this a bit in a posting on the resurgence of wildlife in the Chernobyl area, a while back. Do we need to protect endangered species by dumping radioactive wastes in their habitats to keep humanity out? That is a truly scary thought! But this is the kind of thing that creeps into my brain just before heat exhaustion sets in.

Of course there is always taxidermy. One of my most idiosyncratic pleasures on long road trips through the North American heartland, is to seek out little private museums where people exhibit their moth-eaten collections of stuffed animals and natural history curios. On the same trip, we stumbled upon one such little operation on a back road in the roasting sagebrush steppes of southern Idaho. The museum owners had some deep lava tubes caves on their property, which you could explore for a couple of dollars- well worth it as a respite from the withering heat. Upon exiting the coolness of the lava tube, we entered the run-down museum, which was full of dilapidated taxidermy, animal bones, and most endearingly, an egg collection.

Egg collection

As I understand it, poisons such as arsenic were once commonly used to preserve animal remains used for taxidermy and pose a real threat to museum curators working around them even to the present day. In fact there are taxidermists who have died of arsenic poisoning. Maybe nature is trying to tell us something.

Roadside museum taxidermy, Southeastern Idaho

When does landscape become art? This is something I am asked all of the time about my own ‘botanical interventions’. Over time, vegetative landscapes lose some of the aura of the artist , gardener or horticultural dramaturge and develop a life of their own. But when maintained, they undeniably resonate the aesthetic sense of their creator.

I love driving around the suburban periphery of Vancouver, which is in many ways a city of demented gardens. The lysergic rampancy of vegetation engendered by the rain forest climate butting incongrously against the banality of the cookie-cutter architecture often makes me think that I am on another planet.

Vancouver is a city that labours under the burden of the thousands of failed utopias, projected onto it by everyone who gets sucked into its humid gray vortex. It is the end of the road, the end of the continent – the terminal beach. Everyone seems to be looking for something – some desperately.

Is it paradise which they seek? The junkie prostitute with the bleeding legs, scraping manically at the dust with her fingernails in a Downtown Eastside alleyway is looking for it. The Kitsilano professionals are looking for it also, fleeing up to Whistler in their gleaming metal losenges of exquisite German automotive engineering, slurping latés with the top down.

But it is in their gardens that I think many Vancouverites come closest to finding what they are looking for.

Or rather, it is in the garden that one can create in vegetatitive microcosm one’s own version of paradise, reflecting hopes, aspirations and nostalgia for distant times and faraway places.

Vancouver’s moderate climate and abundant rainfall enable every suburban tract to serve as a protean utopia, ready to be coaxed into any vegetative possibility.

Chinese windmill palms, Scottish heather, Californian sequoias, Italian figs and Japanese flowering cherries all compete in a crazy botanical cornucopia to colonize the tabula rasa left by the clearcutting of the ancient Douglas fir and western red cedar rainforest that once covered the city. These botanical mammoths exist now only in relic form- a few stragglers in the centre of Stanley Park- solemn reminders of the now reversed figure/ground relationship between the extirpitated natural ecosystem and the ‘Kulturlandschaft’- the landscape transformed by human activity.

Simon Schama has an interesting take on this figure-ground dynamic between culture and nature in his Landscape and Memory which tracks the history of our relationship to landscape by mirroring it in our relationship to art.

Viewed in their totality, Vancouver’s suburban gardens recede into our “optical subconscious” as we travel through the neighbourhoods, flavouring our journey but not overwhelming us with ideology or didacticism.

Yet the dialectic of class and identity lurks beneath the seething shrubbery and the verdant turf.

For example, working class immigrants from China often dispense with backyard lawns altogether, upon setting up house in Vancouver. Unburdened by the now diminutized North American notion of living in ersatz 18th century English manor houses, set amid minion-tended greensward, they grow bok choi, garlic chives, Chinese wolfberry and bottle gourds right up to the back door. These productive kitchen gardens are a testament to Confucian ideals of practicality, self sufficiency and economy and the landscape thus created is unapologetically Guangdong- not Giverny.

Italians-Canadians drink their Grappa under carefully tended bowers of grapes and figs, the nostalgic leafy architecture of a half-remembered bacchanalia, transplanted from the ancient sun-soaked earth of the Mediterranean to the rainswept patios of Burnaby.

And then occasionally, very occasionally, somebody creates a landscape so utterly idiosyncratic that it transcends simplistic analyses.

So here it is:

(East Vancouver landscape at Kaslo and East 7th)

All day, I’ve been listening to Stereolab’s ‘Cobra and phases group play voltage in the milky night’ and driving myself crazy doing business analysis spreadsheets as part of my cool ‘sustainability’ MBA curriculum. In the midst of the endless banality of the number streams come some interesting insights.

Risk World reports that the obfuscations of Enron et. al are mirrored by many other publically traded corporations who, (surprise, surprise) fail to report massive environmental liabilities on their balance sheets and are in effect lying to their shareholders. Those nasty little superfund sites and other piles of liability-freighted carcinogenic ejecta are frequently reported as ‘externalities’ and not as the sleeping liabilities that they in fact are. (When I grow up, I want to work for Risk World- just because of the cool name!)

It seems that convential accounting standards in the United States, specifically Standard Financial Accounting Statement #5, SFAS 5 puts environmental liabilities in a wishy washy continuum between contingencies and hard liabilities, stating that “contingencies only have to be put on the balance sheet if they are probably and reasonably estimable.” Since it is hard to estimate the cost of wrecking the planet and making people sick, these costs just don’t show up. (And I thought corporate financial accounting was an exact science.)

Which brings me to the topic of insectivorous plants. For many ‘otaku’ these are coolness itself and it is well worth maintaining one’s own private collection. My Sarracenia purpurea are blooming at the moment with splendid inflorescences. They attract their victims (flies) and drown them in a sticky digestive nectar that fills their tubular trap structures. It’s kind of like Enron.

My Sarracenia purpurea

|

|