Healing the Cut-Bridging the Gap

I conceived Healing the Cut - Bridging the Gap in 1993, in collaboration with artist Janis Bowley, as a response to the Grandview Cut Bridges public art competition. At that time, the city had just completed several new bridges across the Cut, which is a man-made ravine, originally excavated in 1910, to accommodate a railway. The bridge construction was controversial because it destroyed a considerable area of lush, deciduous forest that had grown up in the intervening years and provided important habitat for urban wildlife as well as a visual reprieve from the heavily urbanized landscape. Furthermore, there was a strong suspicion in the community that the bridges had been designed to accommodate widening the ravine, to turn it into a major traffic artery.

Though the original (January 1993) call for artists encouraged proposals that would be "an addition to, or an embellishment of the bridges as constructed," we decided to take a different approach. We focused on the highly visible Victoria Drive bridge, which forms the third side of a triangle bounded by Broadway, a major thrufare, and a section of what was already a badly eroding, deforested ravine. Instead of decorating the bridge, we proposed to replace the obliterated forest and to re-imagine the bridge as a kind of community viewing platform from which pedestrians could observe the processes of ecological restoration. To achieve the latter goal, we incorporated a telescope into the design, to be built into an alcove, halfway across the bridge's span. We planned to restore the ravine's forest using hundreds of willow and cottonwood cuttings, which would root and stabilize the soil until the original alder and big-leaf maple forest re-established itself. To assist in this, we planned to install a number of nest boxes on the slope to bring back the birds that had been displaced by the construction. Their droppings would ensure a continuous 'seed-rain' of native plant species as well as furnish important plant nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorous.

Link to google maps location here

Though we won the competition in 1993, I wasn't given the actual go-ahead to implement the restoration until some years later. There were interesting issues of copyright to be worked out and a long negotiation ensued between the artists and city staff. Since the creation of a living forest was integral to the project, we wanted the same intellectual property protection for it as would be accorded to a public art work of a more conventional nature. As joint copyright holders, the artists needed to be included in any plan to move or otherwise de-accession the work —an arrangement which we realized would add a layer of protection to what would once again become a valuable piece of urban green space. Yet treating an entire piece of landscape as an art work was still uncharted territory, particularly for the city's traffic engineers, because of the limitations that such an arrangement would put on how the land might be used in the future. As the conversation dragged on, Janis, one half of our design team, had to move on to another project she had begun in Australia. Though it took a long time, eventually an agreement was reached and by January 1997, I began the restoration process.

During the four years of negotiations, erosion in the Cut had got significantly worse. The winter rains had gullied the exposed soil and a considerable amount of mud was flowing down the slope. A condominium project that had been built on top of the ravine looked vulnerable to a potential landslide. It was clearly time to start planting trees. In January of '94, I began poking holes into the side of the bank with an iron bar and then inserting hundreds of dormant willow (Salix) and Cottonwood (Populus) cuttings—planting them more densely in the places where erosion was more severe. I planted some rooted whips of Black Locust (Robinia) and Butterfly Bush, (Buddlea) in spots that were too dry to support the Cottonwoods and willows.

The next step was to install a dozen or so nest boxes. I made them from rectangular chimney flues, into which I drilled entrance holes of the right size for Chestnut-backed chickadees and Violet Green swallows. The nest boxes are roofed with a removable ceramic tile, attached with velcro, which allows occasional cleaning out of the old nests, to prevent the build-up of parasites. The boxes are mounted on metal posts situated far enough apart to respect the territorial needs of the nesting birds. To my surprise, a few birds moved in almost right away, likely due to a shortage of other available nesting sites after the bridge construction. The plants established themselves quickly and by May of '94 the slope was greening up.

As the cuttings rooted and sprouted leaves, they created a kind of living 'band-aid' under which the slope could stabilize. In the more rapidly eroding gullies, I constructed living dams, using thick cottonwood cuttings placed horizontally and supported by palisades of vertical cuttings. These simple constructions trapped eroding material behind them, softening the destructive energy of the runoff water. This created little terraces in which seeds deposited by wind and birds could germinate, the growing roots adding further stability to the slope over time. The advantage of these living, 'bioengineered' structures is that they are 'intelligent' and adjust themselves to changing conditions. A willow cutting partially buried by a landslide will develop more roots where it is covered and then extend its twig and leaf growth outward to impede further erosion.

Slide Show:

Grandview Cut before

This picture would have been taken in the early 1990's before the rennovation of the bridges damaged large sections of the Grandview Cut's forest. The landscape had the character of a quiet rural road that ran just beneath a densely urbanized landscape.

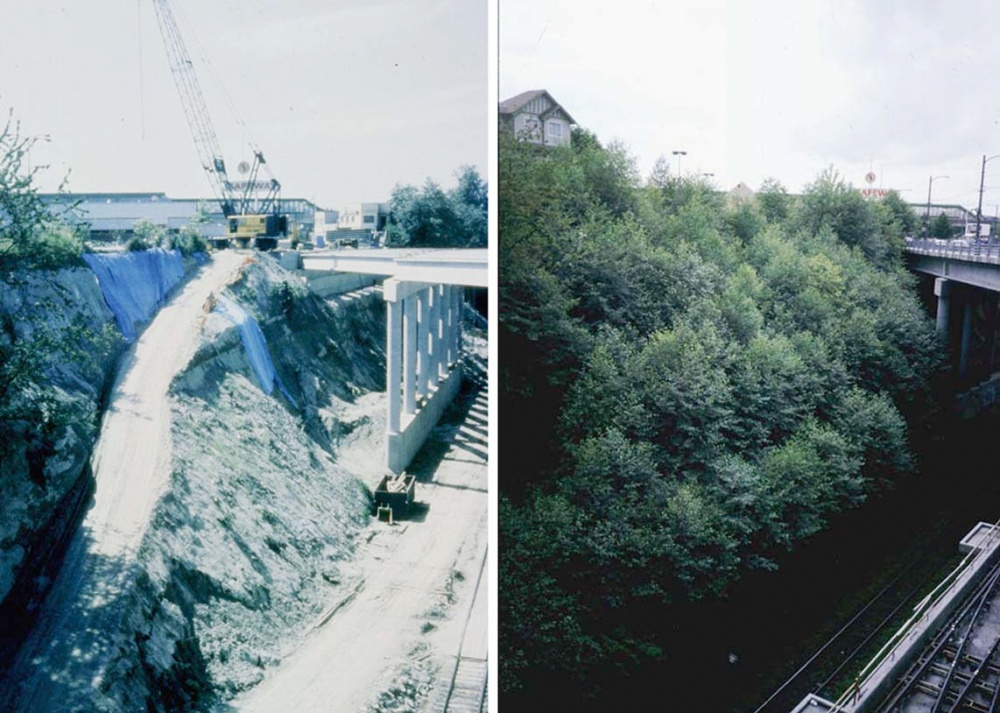

bridge construction

The forested ravine was stripped bare to accommodate the construction of the new Victoria Drive bridge at Broadway.

viewing platform concept

Our original viewing platform concept as sketched by Janis Bowley.

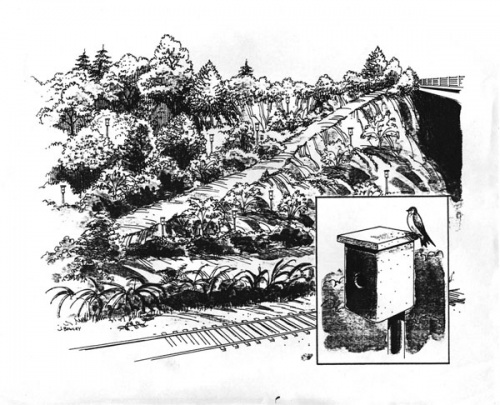

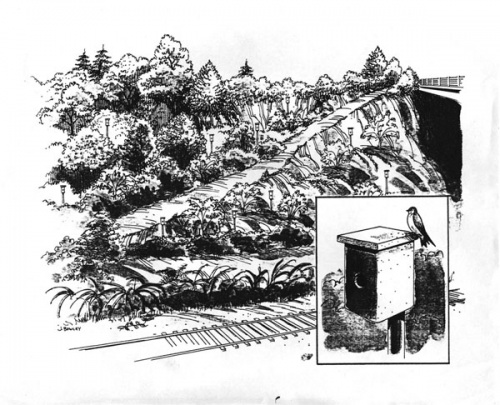

restoration concept

Original sketch by collaborator Janis Bowley of the initial restoration concept. In the end, the access road was removed and I opted to plant a denser arrangement of trees to increase the protection of the soil from erosion. The inset shows the design for the birdhouses, which were constucted from ceramic flue tiles.

rapid erosion

The slope was already rapidly eroding from the time it was stripped of vegetation till I finally was authorized to begin the restoration. The condominium building at the top of the frame was going to be in some serious danger.

the planting process

Here I am with an arm load of willow cuttings and an iron bar.

slope planting with bird houses

I can be seen toward the center of the picture planting willow cuttings on the steep and rapidly eroding slope. I installed numerous bird houses to replace the nesting opportunities that had disappeared with the removal of the trees. Birds distribute the seeds of their food plants via their droppings, which also contain nutrients essential to plant growth such as nitrogen and phosphorous. This 'seed rain' augmented my initial plantings facilitating a much quicker regeneration of the vegetation.

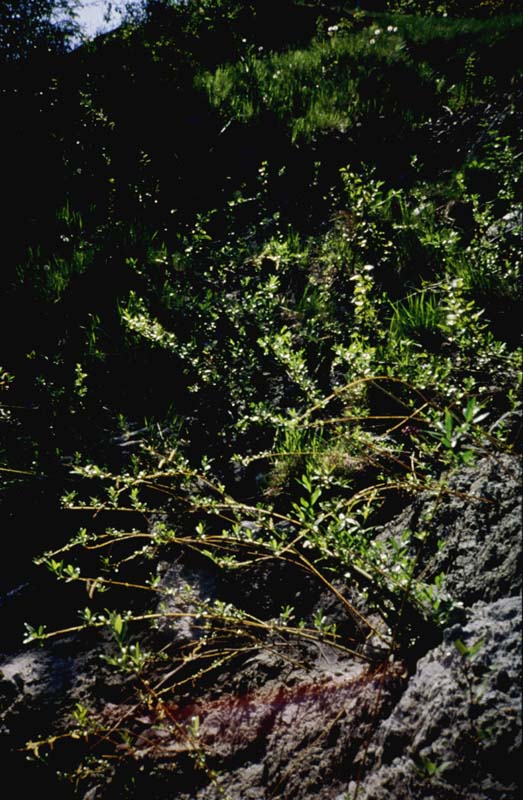

willow cuttings down hill view

I planted hundreds of willow cuttings on the contours of the slope. I planted more densely on the actively eroding zones such as this gully.

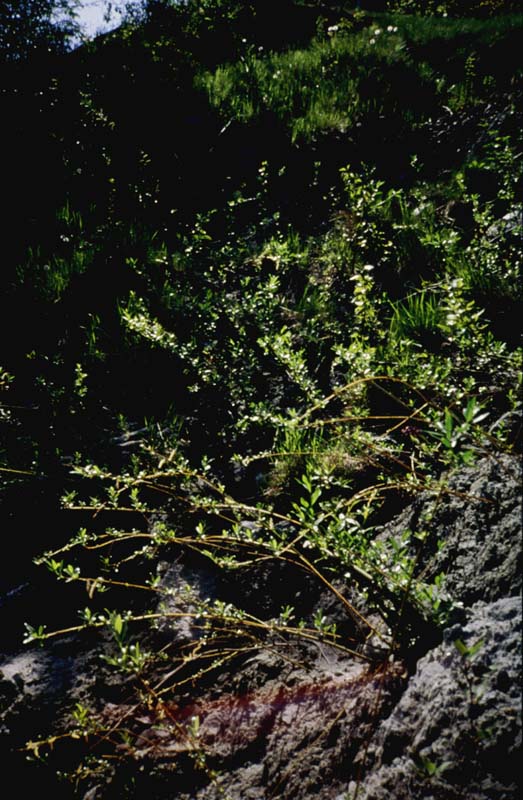

initial green-up

Willows leafing out and rooting into the eroded soil at the beginning of the first growing season.

interceptor dam freshly installed

These Cottonwood and willow cuttings have been newly installed into a rapidly eroding gully of super-saturated soil. Soon they will help stabilize the situation.

interceptor dam greening up

The Cottonwood cuttings I used to make this living interceptor dam are sprouting and rooting themselves into the gully where they are slowing the erosion due to falling rocks and running water.

ravine after after ten years

In less than 10 years, the ravine was completely covered in vegetation both from the material I had planted and from the seeds brought in by the wind and by birds.