Means of Production

Means of Production is a public land art project located at North China Creek Park in the Mount Pleasant neighbourhood of Vancouver, British Columbia.

I conceived the project as a botanical intervention to demonstrate techniques of community-scale ecoforestry in a low-income, inner city neighbourhood, as well as to frame questions about the loss of the notion of the 'commons' in the North American landscape.

The inspiration for the Means of Production project came to me during my work founding the nearby Cottonwood Gardens, where I initiated some plantings of bio-materials ( bamboo, willow, Paulownia and Black Locust) so we could make stakes, trellises and fencing for our produce gardens. It occurred to me then that there were a lot other areas of waste or underutilized urban land, perhaps less suited to the intensive production of food, that could be producing useful bio-materials and perhaps this could form the foundation of community micro-economic enterprise in the way that the traditional 'commons' has functioned for centuries in the context of Europe. The additional services such as wildlife habitat, carbon sequestration, recharging the water table and of course, community empowerment that such a scheme could provide made the concept seem all the more viable and thus the proposal for the 'Means of Production' project was born, its name an obvious reference to Karl Marx's notion of the physical infrastructure required to produce so-called 'wealth.' My idea to focus initially on the production of art and craft supplies came out of my proposition that the landscape itself could be an ongoing art piece, which, when managed by creative people, could serve as a kind of lab or platform where ongoing experiments with biomaterials could be carried out and the public engaged in wider aesthetic discussion as well as encouraged to participate in the site's ongoing stewardship.

Means of Production was intially implemented by me and members of the Environmental Youth Alliance with financial support from the Art & The Environment initiative of the Community Arts Council of Vancouver as well as the Vancouver Parks Board.

Work at the Means of Production site commenced in the fall of 2002 and is ongoing. The landscape is constantly changing as the plantings of heritage basket willow, Paulownia, bamboo, hazel, ash, iris and hollyhock are harvested and new growth cycles start up and the various on-site artistic interventions ebb and flow through time. The harvested materials form the basis of social practice initiatives led by various artists in conjunction with people from the surrounding neighbourhood. I continuing to document each layer as it continues to aggregate into an ever richer palimpsest of human and botanical activity.

In keeping with the open source intention of the the project, the Earthhand Gleaners Society formed and they now co-manage the site. They put on workshops using the materials grown on site as well as offer many other interactive and educational programs throughout the year.

We would be pleased to have you visit Means of Production, which is open to the public year round.

Here is a video made by Patti Fraser of the Pacific Cinematheque documenting the founding of the project:

Link to City of Vancouver Parks Dept. description of site

https://vancouver.ca/parks-recreation-culture/means-of-production.aspx

Slide Show:

The Means of Production Manifesto:

With its explicitly utilitarian didacticism and naturalistic horticultural arrangements, one might well ask:

“What makes The Means of Production a work of art?”

Clearly the project facilitates the production of art by directly furnishing materials for art making but is it itself a work of art?

At first glance, the plantings are quite pleasing to the eye, the bright varicoloured stems of willows and bamboo contrasting with the dark sculptured shapes of the coppiced trees.

In addition, Means of Production is paradigmatic; a working model of inner city forestry and neighbourhood self-sufficiency, an homage to arcadian tradition and ecological agit prop. But this is only part of the aesthetic equation.

In my previous land art work, (Cottonwood Gardens, Healing the Cut- Bridging the Gap, Memory Trees etc.), I have adopted what the late Fluxus artist Joseph Beuys called “the homeopathic role." Here, the artist, and by extension the work, become covert agents of social change.

Beuys, despite his stated aspirations, was himself extremely overt, caught up in the overblown celebrity culture of the twentieth century avant-garde. Yet some of his later works, notably Stadtverwaldung statt Staatverwaltung (also known as Seven Thousand Oaks) pointed out a way toward a new, more subtle artistic mandate.

Considering urban reforestation as art, moves us away from the pervasive banality of the artist as stylish maker of branded fetish objects, purveyed to an ever-shrinking audience of cognoscenti; the kind of art that can at best evoke some small frisson, or a knowing, ironic wink.

Means of Production abandons this game. There is no more secret handshake, no more “Fifteen minutes of fame.”

I succeed only when the viewers of my work forget about me and any cleverness of artifice and begin to experience the work completely as ambiance. Then, they might start asking the questions that I want them to ask. After numerous cycles of harvest and regrowth, any residual aura of me as artist or horticultural dramaturge will have disappeared. It will no longer matter.

That is when it gets interesting . . .

Because then the artwork will have receded into what Walter Benjamin called the optical subconscious – the artist’s unseen hand. The work no longer screams out, “ART”, but becomes part of the infrastructure, part of our assumptions, an internalized component of the urban visual field. In short: The new normal.

planting willows

Members of the Environmental Youth Alliance and I dug swales following the contour of the slope which we filled with mulch to capture run-off. Here we can be seen planting the first of the willow cuttings that would soon grow roots and furnish the basis of our system of production.

young willows

Young willow cuttings just leafing out a few months after being planted.

monolith

I installed a large inscribed granite monolith to serve as a marker around which the 'open-source' landscape would continue to evolve. The phrase 'Means of Production' refers to Karl Marx's terminology, by which I meant that the land itself, which had been a wasteland or 'terrain vague,' would serve as a source of microeconomic opportunity for the surrounding population.

first growth

The basket willows are very fast growing. This was the first summer after planting.

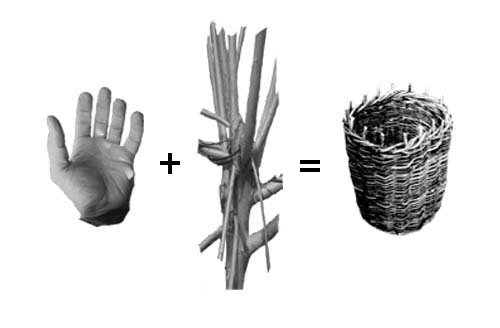

hand + stick = basket

I came up with a simple visual 'algebra' to explain what we were trying to do in a non-verbal fashion.

golden willows

These willows, a golden strain of (Salix purpurea), have been pollarded to increase the colorful young growth.

pollarded willows

Here is a wider angle view of pollarded willows in the winter.

basketry workshop

An early on-site basketry workshop with the Environmental Youth Alliance and Alastair Heseltine.

evolving landscape

Means of Production is constantly changing as people continually interact with the plant material grown on site.

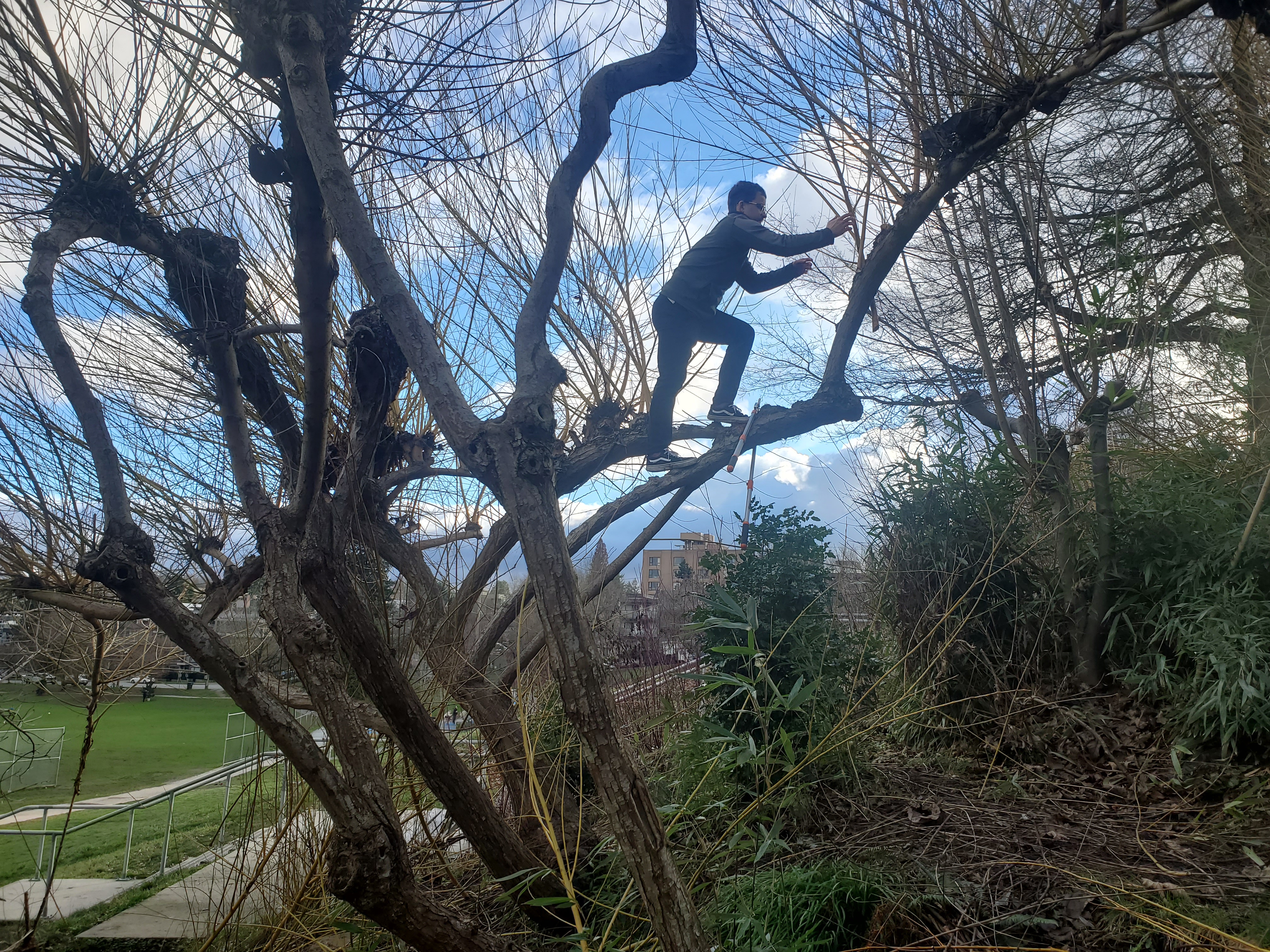

hillside after ten years

Here is a shot of the hill side after ten years of growth

Grafted Willow Arch

Pollarded Paulownia

This Paulownia is seasonally coppiced by musician David Gowman who uses the light yet resonant wood to build custom wind instruments.

Pollarded and Grafted Willows

Willow Arch

Willow harvest 2022

Photo by Sharon Kallis

Willow harvest 2023

photo by Sharon Kallis

basketry workshop in progress

Alistair Heseltine demonstrating basket construction technique atop the monolith.

hazel gates

Gates made from hazel grown on site by artist Sharon Kallis.

hillside in spring

A view up the hillside in early spring. Note the flowering fruit trees that have been added near the bottom of the installation.

newly harvested willow

Basket willows after recently being pollarded.

open source landscape

The continually changing horticultural 'skin' of Means of Production reflects the interplay of the growing plants and those that tend and harvest them.

summer willow

a season's growth of willow, which will be harvested during the winter dormant period.

the monolith after ten years

The monolith provides a stable reference point and a work surface in the midst of its ever-changing surroundings.

willow edging and trellis

Golden willow edgings and a living trellis.

willow harvest

Here are various willow varieties bundled after being harvested on site, drying for future use.

Paulownia wood musical instrument

David Gowman with one of his hand-made Paulownia wood instruments.